Ferocious wildfires are raging across Southern California, destroying hundreds of homes adorned with holiday decorations and forcing thousands of residents to flee. With high winds expected to continue, forecasters are warning that dangerous fires could endanger the region for days.

California is susceptible to fires year-round, but the worst of the wildfires aren’t supposed to occur this late into the year. October is the month when the state sees the worst fires. But higher temperatures and drier conditions are lengthening the season when Californians can expect the worst wildfires.

Extreme heat and years of ongoing drought are both linked to climate change and are increasing wildfire risk throughout California by contributing to the frequency and severity of wildfires in recent decades, according to Climate Signals, a science information project of the nonprofit Climate Nexus.

“Sadly, the danger of wildfire in California is now year-round,” California Insurance Commissioner Dave Jones said Wednesday at a press conference. “The fires burning in Southern California are threatening lives and homes at a time of year historically most of us expected there to be little to no danger.”

Jones held the press conference to announce the latest loss figures from the Northern California wildfires in October. With fires raging in Southern California, though, he prefaced his remarks by providing the latest figures on the wildfire in Ventura County known as the Thomas fire, which has already charred 65,000 acres and driven more than 27,000 people from their homes. “The fires that we’ve seen this fall, again, remind us that fire season is 365 days a year,” Jones said.

Two months ago, a group of fires exploded across Northern California. The fires were among the worst on record in the state in terms of lives and property lost, killing 44 people, burning more than 200,000 acres, and destroying 15,000 homes. Jones provided an update on the insurance claims for the October fires, calling them “staggering.” Insured losses for both the Northern California fires in October currently stand at about $9 billion, he said.

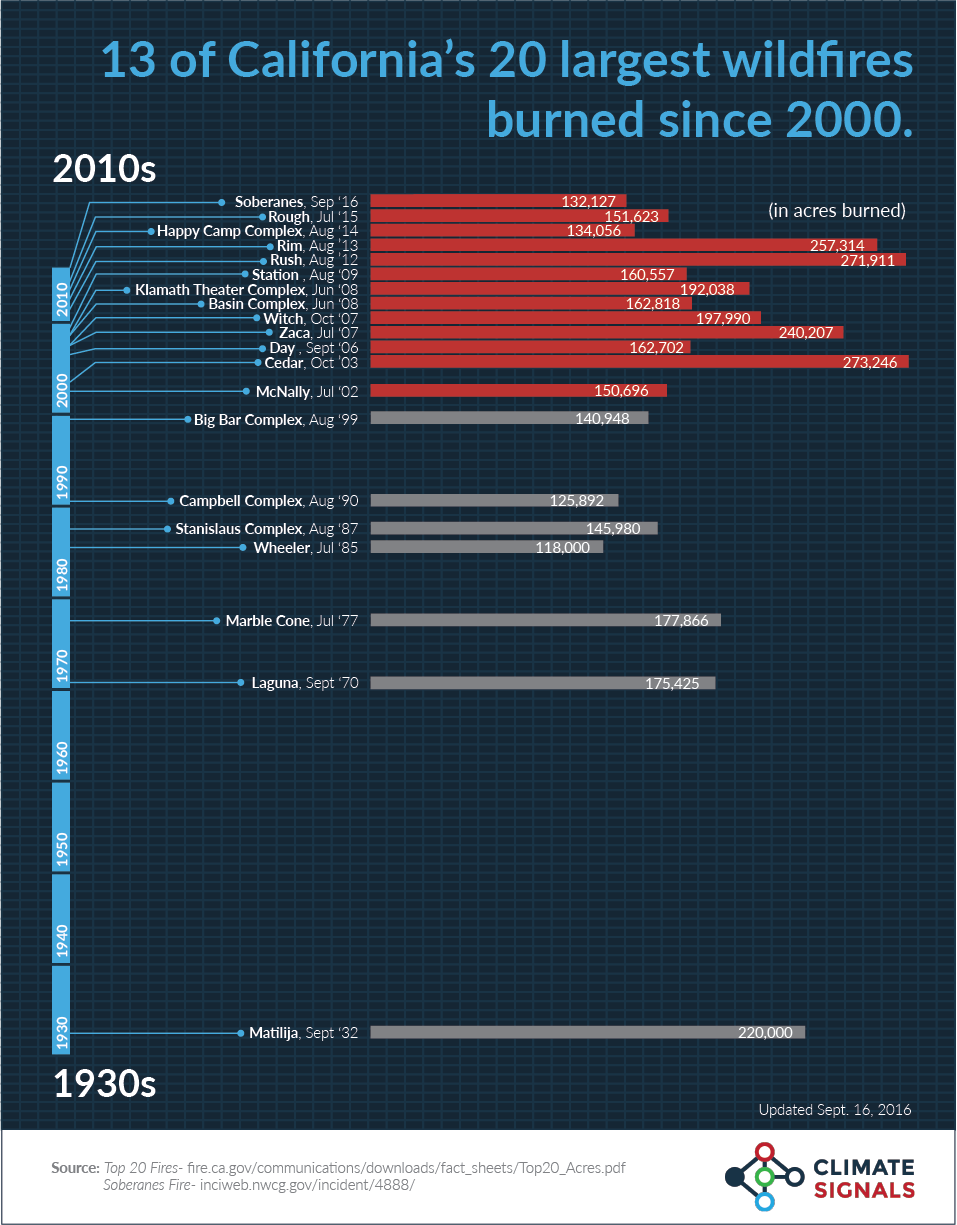

Thirteen of California’s largest wildfires have burned since 2000, according to Climate Signals. Parched forests and longer fire seasons have extended fire-prone land by 16,000 square miles — about the size of Massachusetts and Connecticut combined, the group said. The figures do not include the fires in Napa in October that burned more than 240,000 acres — surpassing all but three of the state’s worst fires.

Since 1970, temperatures in the western United States have increased by about twice the global average, and the region’s wildfire season has expanded from five to seven months on average. From 1979 to 2015, climate change was responsible for more than half of the dryness of western forests and the increased length of the fire season, according to Climate Signals.

Researchers have found that fires stoked by Santa Ana winds, like the ones currently raging in Ventura and Los Angeles counties, burn with more intensity, and they do their worst in a shorter period of time than summer fires. In a typical Santa Ana fire, half of the territory burned is consumed in the first day of the blaze, scientists from UCLA, University of California, Irvine, and University of California, Davis said in a research study.

Southern California’s climate fosters two distinct types of wildfire: rapidly expanding, wind-driven Santa Ana fires that occur mostly in September through December and non-Santa Ana fires that coincide with hot and dry weather mostly in June through September, according to the scientists. Their analysis found that the impact of climate change on Southern California’s fires will be greatest for non-Santa Ana fires.

my car ride to LAX 😱 pic.twitter.com/U29LTa9yAj

— Africa Miranda (@africamiranda) December 6, 2017

In California, the fire season typically peaks in early to mid-October because the state typically gets one or two rain events in the fall, said LeRoy Westerling, a professor of management in the school of engineering at the University of California, Merced and a climate and wildfire specialist. This fall, Northern California received rain after the disastrous fires in October. But Southern California has remained dry, causing the Santa Ana winds to combine with dry vegetation to heighten the fire risk, he told ThinkProgress.

In some areas of the state, the wildfire season is now lasting two months longer due to the dry conditions. Even without new housing developments and suburban sprawl in the Southern California counties, the wildfires would still be causing damage to larger areas of the state than in the past.

“The probability of that happening is increasing because of climate change,” Westerling said. “Climate change makes the precipitation more variable. It’s more likely that you might miss a storm going into the fall and then the vegetation stays dry.”