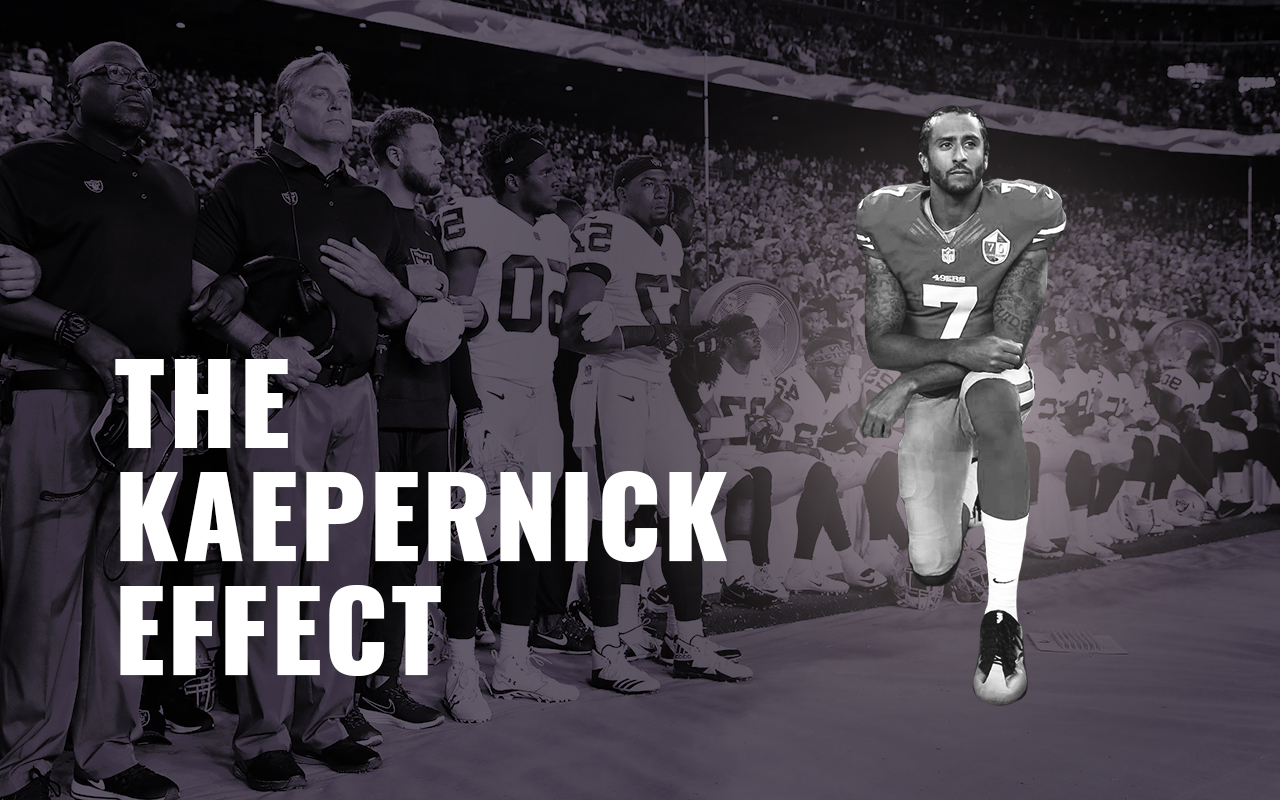

Ever since President Donald Trump referred to football players who kneel during the national anthem as “sons of bitches” in September, public debate over the controversy has largely revolved around discussions of patriotism, the military, and whether demonstrations during “The Star-Spangled Banner” are disrespectful to the troops. But when San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick began the wave of athletes demonstrating against systemic racism last year, his team’s initial statement affirming his right to protest focused on something else.

“In respecting such American principles as freedom of religion and freedom of expression, we recognize the right of an individual to choose and participate, or not, in our celebration of the national anthem,” the statement read in part.

The mention of religious freedom is a subtle gesture to a pervasive — but rarely discussed — aspect of the ongoing national anthem controversy: the role of faith.

Religion, of course, is not a prerequisite to demonstrate against racism or kneel during the anthem. Kaepernick himself does not appear to have publicly tied his protest to his own Christianity — although his mother Teresa repeatedly insists that Jesus was an activist when discussing her son’s advocacy.

But many players joining him this year have cited their spiritual beliefs as a guiding force behind their choice to kneel during the anthem, implicitly linking their protests to a long history of religious Americans dismissing national symbols in an effort to stay true to their faith.

Protest as piety

For San Francisco 49ers safety Eric Reid, opposition to racism and police brutality is a matter of faith. He explicitly said as much in a recent New York Times op-ed, arguing his Christianity moved him to kneel with Kaepernick last year.

“That’s when my faith moved me to take action. I looked to James 2:17, which states, ‘Faith by itself, if it does not have works, is dead,’” Reid, who is connected to various athletic ministries, wrote. “I knew I needed to stand up for what is right.”

“That’s when my faith moved me to take action. I looked to James 2:17, which states, ‘Faith by itself, if it does not have works, is dead.’ I knew I needed to stand up for what is right.”

Other players have voiced similar sentiments. New Orleans Saints running back Mark Ingram told Sports Illustrated he sat during the anthem because “I’m a Christian,” adding, “When I feel something isn’t right, I just want to bring awareness to it.” When Cleveland Browns tight end Seth DeValve kneeled during the anthem, his wife declared he did it because it was the “godly” thing to do. And Patriots safety Devin McCourty said in a September press conference that he and other players decided to take a knee after attending chapel, implying their actions were rooted in an attempt to be true to their faith.

“We were in chapel, and a lot of guys talked about understanding that in our faith God is first,” McCourty said.

The role of religion also extends to protests beyond NFL players. When then-Nebraska University football player Michael Rose-Ivey and two teammates kneeled during the anthem last year, Rose-Ivey told reporters the group prayed as “The Star-Spangled Banner” blared, citing scripture and asking God to “look down on this country with grace and mercy.” When “American Idol” star Jessica Sanchez took a knee while singing the anthem during a Chargers/Raiders game over the weekend, she later justified her actions by referencing the Bible.

Devin McCourty talked about why some of his teammates took a knee during the national anthem. pic.twitter.com/h9LJdSp1QO

— NESN (@NESN) September 24, 2017

Similarly, when country artist Meghan Linsey knelt while performing the national anthem during a game in September, she later told ThinkProgress in a Twitter exchange it was her faith that spurred her to act.

“[J]ust know that my heart was good and I have to listen when the spirit leads me to do something,” she said in a Facebook post. She later added: “Jesus loved everyone and had empathy. Our current president knows nothing about empathy, and I can’t believe how many of his ‘supposed’ followers he has brainwashed.”

A history of religious pushback to patriotic displays

These demonstrators claim different versions of Christianity, but the overarching theme of their faith-fueled demonstrations appears to be a general attempt to honor their spiritual responsibilities first, and blind patriotism a distant second.

That idea can seem radical in contemporary American politics, where the influence of Christian nationalism — which conflates fervent devotion to country with faith — is on the rise. Rev. Robert Jeffress, an adviser to Trump who often proclaims Christian nationalist views, even went so far as to cast aspersions on the faith of NFL players who protest.

“Many of these players claim to be strong Christians, and I believe they are,” Jeffress, whose church choir performed a song invoking Trump’s campaign slogan, said during an appearance on Fox News last month. “And I think they ought to remember what Jesus said — render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s. Jesus said we have a responsibility toward our government. We owe our government not just our taxes, but we owe them our respect and our prayers.”

But the theology of Jeffress and other critics of NFL demonstrators is rejected by several strains of Christianity, some of which have declined to participate in patriotic gestures for decades — with the support of the federal government. As Quartz noted this week, Jehovah’s Witnesses were subjected to beatings and mob violence after the Supreme Court initially ruled their children were required to say the Pledge of Allegiance in public schools, even though saluting national flags was considered idolatrous among members (some of whom had first refused to do so in Nazi Germany). The violence only subsided three years later, when the court reversed its decision after two justices changed their votes.

The majority opinion, penned by Justice Robert Jackson, read: “If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein.”

“I think the broadest theological argument is that God cares for people around the world…And we make our primary commitment to Jesus—i.e., pledging allegiance, so to speak, to the kingdom of God instead of a nation,”

He later added: “Those who begin coercive elimination of dissent soon find themselves exterminating dissenters. Compulsory unification of opinion achieves only the unanimity of the graveyard.”

Mennonites also often refrain from saying the Pledge of Allegiance or standing/singing the national anthem because of a belief that God is ruler of all nations, not just the United States. Loren Swartzendruber — former president of Mennonite school Hesston College in Hesston, Kansas and president emeritus of Eastern Mennonite University (EMU) in Harrisonburg, Virginia — firmly rejected Jeffress’ claims in a phone interview, explaining Mennonite theology puts God above country.

“I think the broadest theological argument is that God cares for people around the world…And we make our primary commitment to Jesus — i.e., pledging allegiance, so to speak, to the kingdom of God instead of a nation,” he told ThinkProgress. “With respect to the national anthem, many of us are pacifist, so the militaristic language of the national anthem is problematic for us.”

Swartzendruber also recalled experiencing fierce criticism over Hesston’s policy of not playing the anthem at sporting events or waving the American flag in isolation around campus — policies mirrored at EMU. He said he received hate mail after the school’s policies became national news in the wake of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, when patriotic zeal hit a fevered pitch.

“I had a three ring binder filled with emails [such as], ‘We wished you had been present in the twin towers [when the terrorists attacked],’ or ‘Why don’t you move to Cuba?'” he said. He noted that he saw “a lot of parallels” between his experience and that of modern-day NFL players chastised for kneeling.

Even Americans who hail from religions with no firm prohibition sometimes abstain from patriotic rituals. Some Jewish day schools reportedly do not recite the Pledge of Allegiance, for instance, as do individual Christians and other religious Americans who claim any number of faiths: In 1995, NBA point guard Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf of the Denver Nuggets cited his devotion to Islam as a reason for declining to stand during the national anthem.

A lasting form of protest?

Although related, most NFL players who cite their faith when protesting aren’t invoking the exact arguments of Mennonites or Jehovah’s Witnesses. Their concerns, theological or otherwise, are more immediate, as are others who protest for more purely secular reasons. Most appear willing to stand for the anthem if circumstances change.

Yet the role of faith remains a factor all the same. And even if the NFL eventually prohibits players from kneeling during the anthem—as the president has repeatedly encouraged officials to do—some demonstrators are already experimenting with new ways to express faithful dissent.

When singer Jordin Sparks performed the patriotic ballad at an NFL game this year, for instance, she used a black marker to inscribe her hand with the words “PROV 31:8-9,” making sure the message was clearly visible on camera.

It was a reference to Proverbs 31:8-9, which reads: “Speak up for those who cannot speak for themselves, for the rights of all who are destitute. Speak up and judge fairly; defend the rights of the poor and needy.”