Of the roughly 1,500 asylum seekers who set off toward the U.S. border last month in the so-called “migrant caravan,” some 50 have reached the border, and, according to immigrant rights group Pueblo Sin Fronteras, some are being illegally turned away.

“There have already been cases of people being illegally turned away by border officials when trying to request asylum at the U.S. border,” a spokesperson for the caravan told Newsweek.

ThinkProgress called Customs and Border Protection (CBP) media officers in California and Washington, D.C. for comment, but did not hear back.

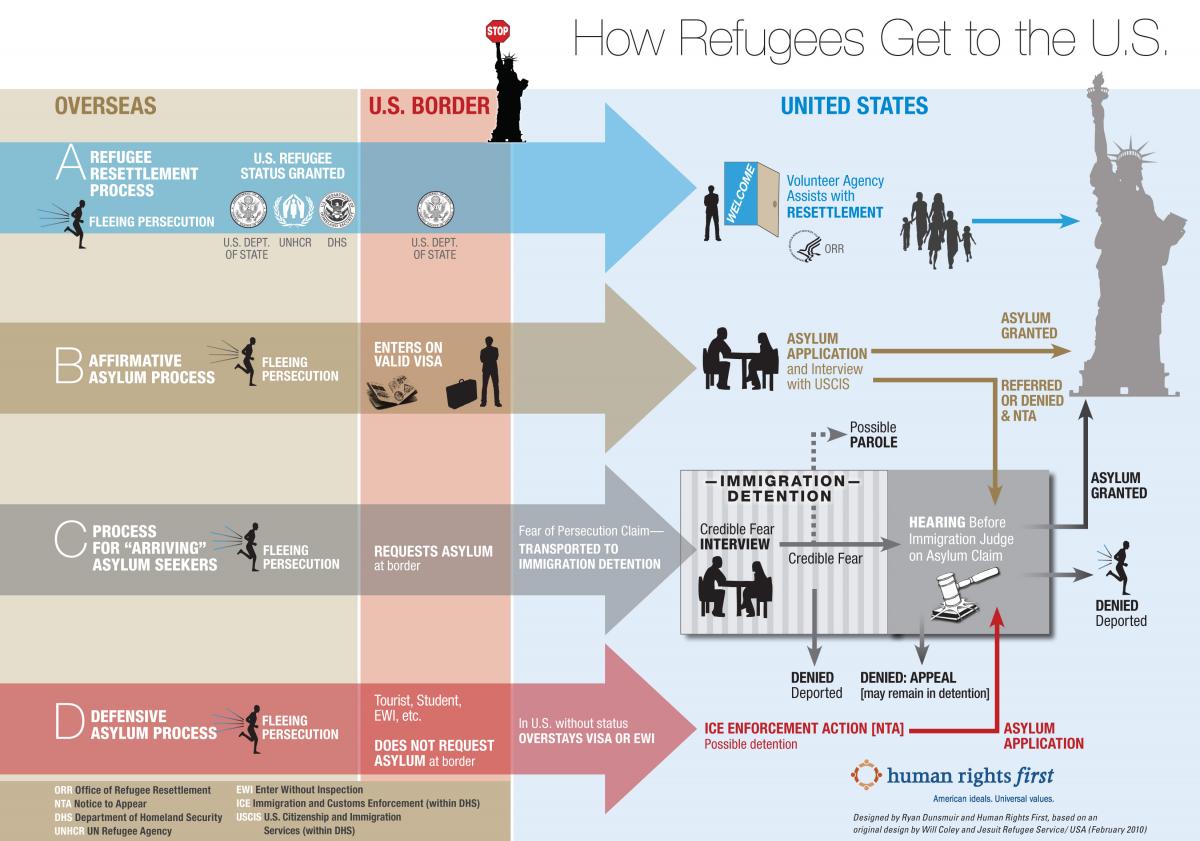

By law, when a person seeks asylum at a border, authorities need to give them temporary asylum (pending an initial security screening) until their application can be considered.

Clara Long, senior researcher with Human Rights Watch’s U.S. Program, told ThinkProgress that turning asylum seekers away at the border is “illegal both under U.S. and international law.”

“They’re supposed to honor your right to seek asylum,” said Long. “They’re supposed to put you into the process to see if your claim is valid,” she added.

This is in fact the subject of a lawsuit, Al Otro Lado v. Kelly, which aims to vindicate the clearly establish international norms around what the right to seek asylum consists of.

The group had been largely dispersed by Mexican authorities, who vetted and returned some back to their home countries. Their movement was also hampered by safety concerns along the way, the Associated Press reported on Friday.

Mexico City was the group’s last stop before the border, but, according to the AP, “Some who had split off to press on alone reported back about kidnappings and having their papers for safe passage torn up.”

Despite the fact that the asylum seekers have not presented a demonstrable security threat to the U.S. border, President Donald Trump called on states to deploy as many as 4,000 National Guard troops to the borders.

Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona have already done so, with California about to follow suit.

Angry that he has not been able to secure funding for his border wall (a rallying cry during his campaign and since) President Trump has also threatened U.S. aid to Honduras — a country from which many asylum seekers take huge risks to flee brutal gang violence.

The big Caravan of People from Honduras, now coming across Mexico and heading to our “Weak Laws” Border, had better be stopped before it gets there. Cash cow NAFTA is in play, as is foreign aid to Honduras and the countries that allow this to happen. Congress MUST ACT NOW!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) April 3, 2018

Trump also threatened U.S. aid to Honduras in a tweet and announced that he was calling for a deployment of the National Guard to the border.

The president has (unsuccessfully) used this tactic in the past — with Palestinians who would not negotiate with Israelis on his terms, and with other U.N. member states who voted against him on his decision to relocated the U.S. embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem.

“What struck me about President Trump’s response was how divorced it was from reality, and how focused it was on painting the picture of fear around the caravan, and the idea that asylum seekers, in general, are a threat to the United States,” said Long.

Border security measures by this administration as well as previous ones, said Long, “are counterproductive.”

“They end up feeding a churn of people who are desperate to return to families because they were deported in arbitrary ways; they provide more power to smugglers, because there are no regularized routes to enter the U.S. to seek asylum, especially when they start turning people away at the ports of entry; and the rapid hiring surges [with the CBP] have historically brought in large numbers of people who seem to be subject to corrupting influences,” she added.

Although the National Guard cannot enforce immigration policy at the border, the appearance of ramped-up militarization will do more harm than good, said Long, starting with what it does to border communities.

“The experience with having the military at the border, historically, has not been good…in the 90s, when the military was involved with active enforcement at the border, it resulted most notably in a teenage high school student in El Paso being shot to death by a National Guardsman,” she said.

Living in a border community can already feel like living in a militarized zone, even if the National Guard is prone to show more discipline than the CBP.

Furthermore, said Long, having people show up at a border to seek asylum “is not a security issue — it’s a normal function of border authorities to facilitate that right.”

The caravan is an annual march meant to raise awareness on migration issues and is not intended as a way to deliver asylum seekers to the U.S. border, but given the dangers facing migrants walking through Central America, some join the march to seek safety in numbers.