On Monday morning, the Environmental Protection Agency released its proposed rule to limit the amount of carbon pollution that existing power plants can dump into the atmosphere. This is the most significant move President Obama has made to address the direct causes of climate change.

The Clean Air Act, passed by Congress in 1970 and amended in 1990, is finally getting to tackle carbon pollution from the nation’s 491 smoke-spewing coal power plants. Contrary to what fossil fuel advocates claim, though, it does not mean that EPA will be directly shutting down coal plants. Each state would have a broad menu of carbon-cutting options, including energy efficiency improvements, adding clean energy sources, implementing a carbon tax, or instituting or joining a cap-and-trade system.

By 2020, states will have to have drop their carbon emissions from existing power plants 25 percent from 2005 levels. By 2030, according to the proposed rule, those emissions will have to drop another 5 percent — to 30 percent — from the same base 2005 level.

Here are 8 things you should know about the new rule:

This is the most significant move any U.S. president has made to curtail carbon pollution in history.

It would be the first-ever action to reduce carbon pollution from an existing source in U.S. history. Using the authority granted to the EPA by the Clean Air Act that Congress passed decades ago, every state will need to find ways to lower the carbon dioxide emissions coming out of the fossil fuel-burning power plants. The electricity sector is the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in the United States. Dropping those 25 percent in 6 years is significant — it amounts to roughly 300 million tons of annual CO2 reduction.

In the rule filed on Monday, the EPA proposed “state-specific rate-based goals for carbon dioxide emissions from the power sector, as well as guidelines for states to follow in developing plans to achieve the state-specific goals.”

This has additional benefits beyond greenhouse gas emission reduction, dropping pollution that causes soot and smog 25 percent by 2030, according to an EPA fact sheet. The EPA also said it would “avoid up to 6,600 premature deaths” and 150,000 asthma attacks in children. When you lower CO2 emissions from coal-fired power plants, you also lower the emissions of other pollutants like nitrogen oxides, particulate matter, mercury, and sulfur dioxide.

There are many opinions of what method is best to lower emissions: carbon tax, cap-and-trade, clean energy incentives, direct regulation. All that matters for those concerned about climate change, in the end, is whether emissions drop, and how quickly. The Council of Foreign Relations’ Michael Levi points to EIA analysis of the likely impact of a carbon tax and other climate bills on power plant emissions. A $25-per-ton carbon tax would be far more effective, dropping emissions 47 percent by 2020 and 66 percent by 2030 — and the cap-and-trade bill passed by the House would have lowered emissions 56 percent by 2030 according to the EIA. The EPA’s proposed target, however, achieves reductions comparable to a far lower carbon tax, the Senate’s 2010 American Power Act, and 2012’s Clean Energy Standard Act. Levi suggests that the 2030 could be seen as a moving target — it could be ratcheted down through additional legislation or new regulation.

Indeed, the EPA could finalize this rule next year with a stronger target, especially if it receives a great deal of feedback from the public. Many environmental groups will be pushing for more ambitious targets later in the decade, even as they nearly unanimously applauded the regulations.

There is room for improvement, and time to improve it.

There is a good reason the government is using 2005 as the base year for emissions reductions. It matches the target set by the U.S. and the U.N. in 2009: a 17 percent emissions cut by 2020 from 2005 levels. The targets in the proposed rule apply only to the electricity sector, while the 17 percent target is for all sectors of the economy. At the same time, using that year allows the EPA to be less aggressive than if it used a more recent year when emissions were lower.

In 2005, U.S. power plants emitted over 2.4 billion tons of CO2 into the atmosphere. These levels dropped after 2007, to just over 2 billion tons in 2012. The proposed rule’s target means that carbon pollution from the nation’s power plants would have to drop to roughly 1.8 billion tons by 2020, and 1.68 billion by 2030.

In 2013, energy-related carbon emissions jumped back up 2 percent in the U.S. after several years of decline. This was mainly because coal use increased as natural gas priced inched up a bit. Though the 25 percent drop by 2020 does get things moving in the right direction, the fact that the 2030 target is just 30 percent does not appear particularly aggressive on its own.

The Natural Resources Defense Council’s plan would drop emissions by 20–30 percent by 2020 from 2012 standards, meaning roughly 1.4 billion tons of CO2 at the most. NRDC estimated furthermore that the $21 billion initial cost would be paid back twofold by $51 billion in public health benefits and avoided climate impacts by 2020. EPA estimates that by 2030, the rule will yield “net climate and health benefits of $48 billion to $82 billion.”

The EPA is just doing what Congress (and the Supreme Court) told it to do many years ago.

Though the EPA is simply carrying out the letter of the Clean Air Act in acting to regulate carbon dioxide as an air pollutant, as the Roberts Court ruled it had the authority to do in 2007, there would not have been the need to do so if Congress had acted a few years ago.

The House passed a cap-and-trade bill in 2009, but the Senate did not vote on a bill, dooming a strong campaign for comprehensive climate legislation. This put even more impetus on the EPA’s rulemaking authority to rein in carbon pollution.

So the Obama Administration is taking action not only because it will be a big first step toward a low-carbon future, but because it is executing the laws of the land in the way the Supreme Court affirmed 7 years ago.

States will have huge amounts of flexibility to comply.

As Dan Utech writes in a White House blog post, there are 50 ways the “EPA proposal can be implemented.” The rule divides up the pathways states can use to achieve these carbon pollution reductions into four basic groups: lowering individual plant emissions, switching generation to to natural gas combined cycle plants, switching generation to clean, low-emissions renewable energy, and lowering electricity demand or increasing efficiency. Clean Air Act wonks refer to these pathways as Best System of Emission Reduction, or BSER.

“This plan is all about flexibility,” said EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy Monday morning. “That’s what makes it ambitious, but achievable. That’s how we can keep our energy affordable and reliable. The glue that holds this plan together, and the key to making it work, is that each state’s goal is tailored to its own circumstances, and states have the flexibility to reach their goal in whatever way works best for them.”

The rule also highlights regional compacts like the Northeast’s Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative as progress that can already be taken into account for emission reduction achievements, and could serve as a model for other states. McCarthy put it this way: “If states don’t want to go it alone, they can hang out! They can join up with a multi-state market based program, or make new ones. They’re doing it now.”

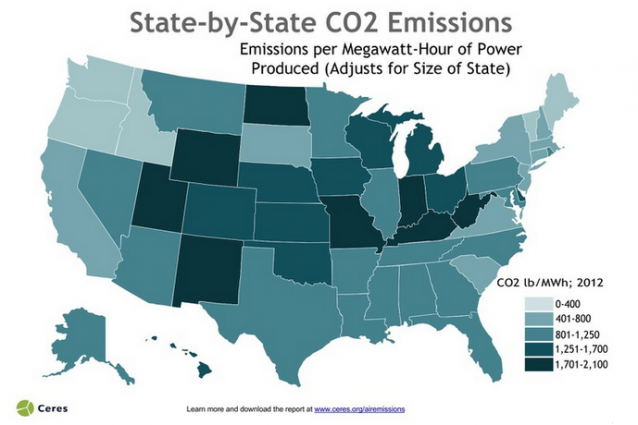

A report earlier this month by Ceres looked at how carbon emissions varied widely by state, and the most carbon-intensive states offer an easy rubric of where much of the state-based opposition will originate.

Coal was on its way out and this speeds up the transition.

The fossil fuel industry, conservative groups, and politicians from coal-heavy conservative states greeted news of the details of the proposed rule with predictable attacks. A coal industry lawyer told the New York Times that the rule “is designed to materially damage” the fossil fuel industry, household budgets, and jobs. Nevermind that coal was already on its way out for other reasons: 60 gigawatts of dirty plants were expected to retire anyway by 2020.

These groups will try to fight the rule in court, and though the lawsuits could slow down implementation, the Clean Air Act is clear, and so have the courts: the EPA has the authority to regulate carbon dioxide. In fact, if it does not, it opens itself to arguably much stronger lawsuits petitioning it to regulate CO2.

This is one rule in a long string of carbon-cutting actions since President Obama took office.

Electricity production churns out almost a third of America’s greenhouse gas emissions, followed by the second-largest source: transportation. In President Obama’s first term, following EPA’s Supreme Court-permitted “endangerment finding” that carbon pollution was a danger to human health and welfare, the federal government moved to double fuel economy in light vehicles by 2025.

Last June, President Obama unveiled his Climate Action Plan, which had three main goals: cutting carbon pollution in America, leading international efforts to cut global emissions, and preparing the U.S. for the costly impacts of climate change. Many of the items on his laundry list have seen action in recent months, including reducing methane leaks.

The rule won’t come into effect overnight.

This is a proposed rule, and will not be finalized until next year, after which the states would have a year to draft and submit their plans on how they will achieve their emissions reductions. If EPA approves, those states are off to the races. If not, EPA can just submit their own plan for the state.

And after it takes another look at the carbon rule for new plants, it can revisit the finalized rule for existing plants — it has 8 years to do so. This means that in 2022 or 2023, they can update the rules, leaving plenty of time to implement stronger state standards.

It’s not just fossil fuel companies and conservative groups that have a voice in this process.

Perhaps the most important takeaway is that though this is the most significant step the U.S. will take to cut carbon pollution, it is, still just a proposed rule. The agency announced four public hearings: on July 29 in Atlanta, GA and Denver, CO; on July 31 in Pittsburgh, PA, and during the week of July 28 in Washington, DC. EPA will be soliciting comments from all Americans before it is finalized next year. Anyone in America can comment on the proposed rule here.