Evangelical Christians are up to something new.

At least that’s the position of many criticizing the “Nashville Statement,” a controversial document championing “biblical” sexual ethics that was penned this past week and signed by roughly 150 prominent evangelical leaders. The document, divided into 14 articles and released by the Council on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood (CBMW), mostly parrots denunciations of LGBTQ identities and relationships common among right-wing evangelicals. But it drew added attention for doing something unusual: extending their condemnation to Christians who affirm queer people.

“We affirm that it is sinful to approve of homosexual immorality or transgenderism and that such approval constitutes an essential departure from Christian faithfulness and witness,” Article 10 of the statement reads. “We deny that the approval of homosexual immorality or transgenderism is a matter of moral indifference about which otherwise faithful Christian should agree to disagree.”

The statement triggered outrage almost immediately, especially among LGBTQ and LGBTQ-affirming Christians who saw it as a direct attack on their understanding of the faith. Within hours, several progressive Christian groups issued their own counter-statements refuting the evangelical document point-by-point, with some deriding it as “anti-LGBTQ bigotry.” Faithful America, an online advocacy organization for progressive Christians, already has thousands of signatures for a petition rejecting the statement.

Others argued that the timing of the statement, published in the aftermath of tragic racist violence in Charlottesville (when many evangelicals stood by Trump despite his defense of those who marched with white nationalists) and as Texas struggled to recover from Hurricane Harvey, seemed insensitive.

“From the very beginning of the Christian faith, sexual morality has always been central … These are not new teachings. They are the ancient faith.”

Nashville signatories—which included some leaders who advise President Donald Trump—defended themselves by insisting they were simply appealing to “ancient” Christian teachings, albeit in ways that were atypically firm. CBMW president Denny Burk even went out of his way to insist that Article 10 was meant to be polemical.

“From the very beginning of the Christian faith, sexual morality has always been central,” Burk wrote. “Those who wish to follow Jesus must pursue sexually pure lives. A person may follow Jesus, or he may pursue sexual immorality. But he cannot do both. He must choose. One path leads to eternal life, and the other does not. These are not new teachings. They are the ancient faith.”

He went on to describe Article 10 as “a line in the sand,” noting, “anyone who persistently rejects God’s revelation about sexual holiness and virtue is rejecting Christianity altogether, even if they claim otherwise.”

It was our aim to say nothing new, but to bear witness to something very ancient. @benshapiro #NashvilleStatement https://t.co/mlXiMsv43n

— Denny Burk (@DennyBurk) August 30, 2017

Despite the confidence of the signatories, however, Bible scholars and historians told ThinkProgress the implicit claim that anti-LGBTQ positions have always been “central” to the Christian faith is not only offensive to many—it’s also downright false.

Rather, the core of the Nashville Statement appears to be a very modern attempt to reimagine Christianity in ways that are culturally (and possibly politically) expedient for present-day right-wing evangelicals and other conservative Christians.

Re-centering Christianity around conservative sexual ethics

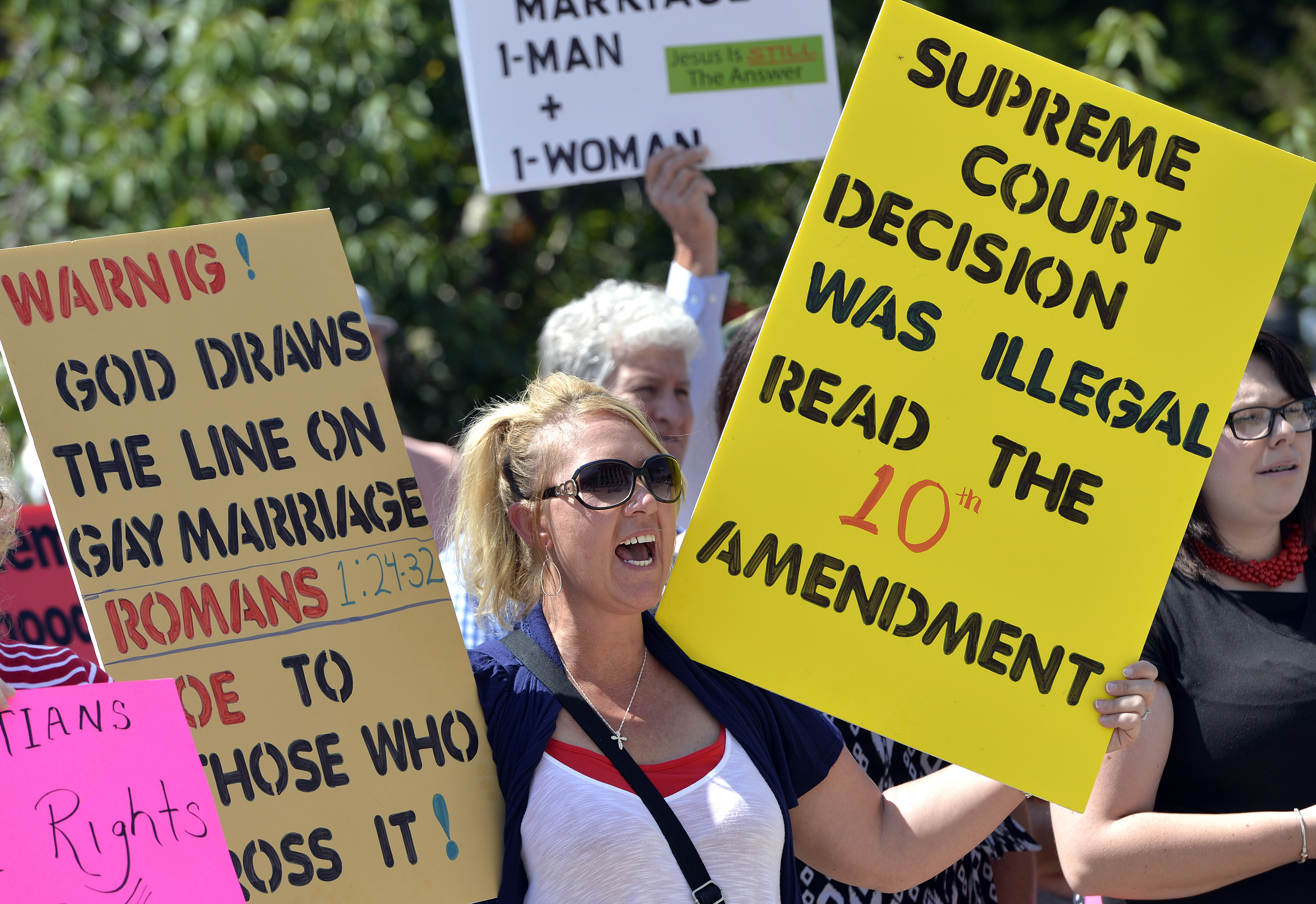

The Nashville Statement is hardly the first time conservative American Christians have argued against LGBTQ identities and relationships. If anything, the document is the culmination of a years-long push to make anti-LGBTQ theology obligatory for evangelical leadership or even membership.

The examples of this theological re-centering process—wherein a specific definition of sexual ethics is touted as paramount for Christianity—are overwhelming. The Religious Right has spent decades claiming opposition to same-sex marriage as central to their public Christian identity. More recently, Rod Dreher’s book The Benedict Option argued Christians should retreat from society primarily in response to the legalization of same-sex marriage, and refers to mainline Christians (who are far more likely to affirm LGBTQ people) as “moralistic therapeutic deists.” Major evangelical Christian organizations and theologians have been ostracized or financially threatened simply for entertaining support for marriage equality, evangelical campus groups purge those who theologically support LGBTQ rights, and many evangelicals argue that just serving LGBTQ people can be a violation of their religious principles.

Yet even as right-wing Christians (a group that includes evangelicals as well as conservative Catholics and other groups) have trumpeted these beliefs, their moderate and progressive cohorts have broken in a very different direction. Entire denominations such as the United Church of Christ vocally affirm marriage equality, and historic groups such as the Episcopal Church, Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, the Presbyterian Church (USA) and others ordain LGBTQ people and allow ministers to perform same-sex marriages.

In fact, right-wing evangelicals and conservative Catholics increasingly find themselves in the minority. According to PRRI, white evangelical Christians are currently one of very few major religious groups with majority opposition to same-sex marriage, with most Catholics now embracing the practice. White evangelicals are also the only group surveyed to report majority support for allowing small businesses to deny services to gay or lesbian people on religious grounds.

The shift has been peculiar, especially as groups that once fought wars with each other over different theological disputes (e.g., Catholics and Protestants in Europe) have suddenly found common ground—all while never renouncing their original differences.

Early Christians weren’t super excited about marriage

Despite the slow national embrace of LGBTQ rights, dwindling support for conservative Christian admonitions of queer identities and relationships is often lifted up by right-wing leaders as evidence of orthodoxy. In addition to claims of “persecution” at the hands of “secular culture,” evangelicals and conservative Catholics often claim their “counter-cultural” position on sexuality and gender identity is deeply traditional.

But does that make the precepts of the Nashville Statement in line with ancient Christians?

“In a word, no,” Candida Moss, theology professor at the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom, told ThinkProgress in an email.

Karl Shuve, assistant professor of Christian History at the University of Virginia, was even more dismissive.

“[The Nashville Statement] is not a document that is seriously interested with the witnesses of the Christian past, nor is it interested in engaging seriously with the issues underlying marriage and gender identities of the present…[it’s] trying to give the air of deep and rich tradition to something that is very modern, very new, and in some ways very reactive.”

“This is not a document that is seriously interested with the witnesses of the Christian past, nor is it interested in engaging seriously with the issues underlying marriage and gender identities of the present,” Shuve, an expert in early and medieval Christianity, said. He added he had trouble “getting past” the first article of the statement, describing the entire document as “something that is trying to give the air of deep and rich tradition to something that is very modern, very new, and in some ways very reactive.”

Moss, who previously taught at Notre Dame, characterized many of the Nashville Statement’s claims as ahistorical. She noted, for instance, that it idealizes the “traditional” heterosexual family unit, yet many early Christian communities were far less dogged in their support for marriage. Instead, they often preferred celibacy.

“One of the most distinctive things about ‘ancient’ Christian morality is the fairly pervasive lack of interest in marriage,” Moss said. “While early Christians see marriage as permissible, especially people who weren’t able to exercise self-restraint, it was better to remain unmarried and never have sex. Comparatively speaking, there was less support for ‘traditional marriage’ among early Christians than there was among ancient Romans.”

Shuve echoed Moss’ claims, noting that some early Christian leaders encountered pushback for their stalwart support of unmarried virginity. The Nashville Statement, by contrast, never encourages heterosexual Christians to remain unmarried.

“In the 4th century, you had Christians renounce marriage altogether,” he said. “We have one instance in Milan where a bishop faced a huge amount of pressure for promoting virginity.”

The ancient Christian discomfort with marriage came from several sources, but experts say their views were largely rooted in scripture. Brennan Breed, an assistant professor of Old Testament at Columbia Theological Seminary who has written extensively about sexual ethics and the Bible, pointed to 1 Corinthians, where the biblical writer Paul pushes celibacy as the preferred option for Christians.

“In early Christianity, Paul very clearly believes that celibacy is the best thing for people to pursue—because he believes the end times are coming very soon,” Breed said. “Paul is advocating that family is pretty much useless, and it’s only a secondary option for those who can’t commit themselves to being a full Christian.”

Early Christians had no concept of modern same-sex couples

All three scholars were quick to note that sex and gender have long been topics of debate for Christian communities. But while some scriptural passages and community practices arguably ostracized LGBTQ people, Moss and others said such disagreements weren’t “central” to ancient Christian identities.

“Sexual ethics make up a very small percentage of the ethical content of the New Testament and, even then, the majority of the sexual ethics concerns the question of divorce and the behavior of married spouses,” Moss said. “The only sin that is identified as unforgivable in the New Testament is ‘blasphemy against the holy spirit’ and for much of the first 400 years of the Christian era it was apostasy that was the central ethical concern for Christians … Was there, during this period, condemnation of LGBTQ identities and behaviors? Yes. Was this central to what it meant to be Christian? Absolutely not. The idea that you have to condemn LGBTQ identities to be a Christian is not older than LGBTQ advocacy.”

Moreover, Shuve notes that passages often interpreted as condemning LGBTQ behavior don’t account for the modern conception of committed, partnered same-sex relationships. Instead, he says, they were mostly concerned with the behavior of ancient Romans, where wealthy older men would sometimes have sexual relationships with male slaves.

“Sexual ethics make up a very small percentage of the ethical content of the New Testament and, even then, the majority of the sexual ethics concerns the question of divorce and the behavior of married spouses.”

“The idea of sexual orientations—these do not exist in the Roman world, or the greek world,” he said. “The fact is, there has never been a robust discussion of marriage on the terms that marriage is understood in the present today.”

Context, as it turns out, is king—both for early Christians and for Biblical figures. Breed referenced several instances in the Old Testament where God’s decrees changed after Moses had conversations with the divine, usually in an attempt to better suit situations encountered by ancient Hebrews. Even the Ten Commandments shifted slightly, undergoing tiny alterations between their initial introduction (Exodus 20) and later references (Deuteronomy 5).

“Even the Ten Commandments needed to be contextualized,” Breed said. “There are minor differences that seem to reflect contextual changes in the narrative of the Pentateuch [the first five books of the Hebrew Bible]…What we’re supposed to do with that is revisit these ancient texts, revisit the norms of these communities. This process will never be over.”

Early Christians played a lot with gender

Scholars say conservative Christian condemnations of transgender identities, which the Nashville Statement denies is “consistent with God’s holy purposes,” are also spurious when put in context of the ancient church. In fact, Shuve says hardline views of biological gender determination would likely confuse early followers of Christ.

“Early Christians did not subscribe to the same sort of [idea of] biological identity being wholly determinative,” Shuve said. “The idea of women becoming men was common—not biologically, perhaps, but spiritually to obtain salvation. [In some texts] the way a woman attained salvation was to symbolically become a male.”

Shuve pointed to several early examples of Christians playing with gender identity. He singled out Gregory of Nyssa, a fourth-century theologian revered as a saint in several traditions, who preached that gender was, spiritually speaking, unimportant.

“Early Christians did not subscribe to the same sort of [idea of] biological identity being wholly determinative.”

“For Gregory, gender is extraneous to human identity,” he said. “So for Gregory, we are a kind of hybrid. It’s not essential to our human nature that we are male and female.”

It’s possible the Nashville Statement tries counteract this idea by referencing a revisionist interpretation of Gregory in Article 4, but the late saint is far from the only early Christian figure to play with concepts of gender.

“There are many Christian heroes during [the early Christian] period — Saints Sergius and Bacchus, for example — whose behavior complicates the idea of a consistent Christian sexual [and gender] ethic,” Moss said. “They were Christian soldier martyrs who denied their wives, were dressed as women, and embraced their identities as ‘brides’ of Christ. It would be anachronistic to talk about them as trans-persons or ‘gay,’ but they certainly discredit the idea that Christians have always condemned this kind of thing.”

The statement’s reference to eunuchs—a term used in antiquity to describe those born with atypical genitals and those who chose to be castrated, among others—also struck scholars as interesting, but incomplete. The statement affirms Christ’s reference to “eunuchs who were born that way in their mother’s womb,” for instance, but says they should “embrace their biological sex insofar as it may be known.”

Breed added that Nashville signers seemingly ignore Christ’s other reference to eunuchs in the same passage: namely, that followers “that can” should accept “eunuchs who have made themselves eunuchs for the sake of the kingdom of heaven.”

“That really is a trapdoor in this argument,” Breed said.

Christians change, including evangelicals

It’s important to dispel any notion that ancient Christianity was especially progressive by most modern definitions. Early devotees played with gender partly because gender was a way to enforce patriarchal norms; Shuve noted referring to the church as the “bride” of Christ was partly because Jesus was male, but also partly because maleness was seen to be superior.

“The Nashville Statement resonates with people who are thoroughly modern, who are concerned about the post-modern world. But they would also be concerned by the pre-modern world.”

But Christianity changed. Over time, scholars say, different theologians pushed new interpretations of scripture or tradition, and new contexts forced Christianity to respond to new challenges. This, Breed explained, is part of how Christianity works: It adapts.

“For me as a Christian, we are not a religion that is bound to a particular time and place, a particular language, a particular culture,” Breed said, noting that Peter and Paul debated and ultimately changed understandings of Christianity in the Biblical Book of Acts.

The roles of women in Christianity have shifted over time, for instance, and the Nashville Statement itself affirms that men and women are equal. But Shuve observed that gender hierarchies may be the one thing Nashville signers and early Christians do, in fact, have in common: The overwhelming majority of the signatories were men, and God is referred to as “he” throughout.

When it comes to sexual ethics, however, scholars say much of what evangelicals call “ancient” in the Nashville Statement simply isn’t. Their claims reflect relatively new interpretations of new issues, and may have more to do with apprehension about the future than solipsistic appeals to an imagined past.

“The Nashville Statement resonates with people who are thoroughly modern, who are concerned about the post-modern world,” Breed said. “But they would also be concerned by the pre-modern world.”