On Thursday New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced that cleaner air is now preventing nearly 800 deaths and 2,000 emergency room visits annually. He was speaking as part of a week of climate-related events in the city that coincides with the release of the Fifth IPCC Assessment report.

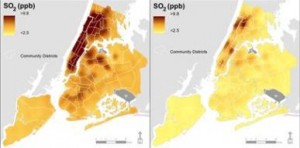

Bloomberg said the level of sulfur dioxide in the air has gone down by 69 percent since 2008 and that the level of soot pollution has gone down by 23 percent since 2007. The numbers come from the city’s Community Air Survey, which measured street level air pollution at 150 locations from 2008 to 2010 and at 100 sites from 2010 to 2013.

Through the efforts of the NYC Clean Heat Program, which requires buildings to convert from heavy forms of heating oil to cleaner fuels, over 2,700 buildings have converted to cleaner fuels since 2011 and an additional 2,500 buildings are actively pursuing conversions.

“By bringing together the real estate community, natural gas utilities, heating oil suppliers, contractors, non-profits and community groups and major lenders, the Clean Heat program has coordinated the entire marketplace to help solve one of New York City’s longest standing air quality problems,” said Director of the Mayor’s Office of Long Term Planning and Sustainability Sergej Mahnovski. “This same approach can help us to increase energy efficiency in buildings and reduce our greenhouse gas emissions.”

Five years ago a report showed that heating oil caused more soot in New York City than all the cars and trucks combined. As part of PlaNYC Bloomberg has set the goal for New York City to have the cleanest air of any major U.S. city. His administration has worked with banks, energy providers and non-profits to try and achieve this.

Since 2008, sulfur concentration in New York City has declined by 69 percent.

CREDIT: NYC DOHMH

The climate change chapter of PlaNYC calls for 30 percent reductions in GHGs by 2030 and potentially 80 percent reductions by 2050. According to the chapter, New Yorkers currently experience an average of 14 days a year with temperatures over 90 degrees Fahrenheit, but by the 2080s it could be more than 60 days. New York is also a coastal city facing threats from sea-level rise and extreme weather events such as Hurricane Sandy.

Urban areas are estimated to be the source of approximately 80 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. This percentage is likely to grow. For the first time ever, the majority of the world’s population now lives in a city. By 2030, six out of every 10 people will live in a city, and by 2050, this proportion will increase to seven out of ten people — about 60 million new urban residents every year.

Cities are now a focus of fighting climate change as cleanliness and public health become more important to urban residents and they have time and income to consider quality of life issues. Some urban residents are being exposed to horrible conditions (such as the smog in Beijing earlier this year). This new climate focus is also in part due to the inefficient and complex global effort that is lagging behind localized climate-change related impacts such as air pollution, sweltering heat waves, and devastating flooding.

In a recent interview between Henry Kippen, a visiting fellow at the Royal Society of Arts, and Benjamin Barber, author of the book “If Mayors ruled the world” they discuss the role cities can play in fighting climate change.

“If you look at the attempts to follow up Kyoto at Copenhagen and Rio, the bad news was that about 180 nations showed up to explain why their sovereignty did not permit them to do anything,” said Barber. “The good news, however, was that mayors were convening as well as heads of state. They stayed on, signed protocols and took action.”

Barber argues that in cities, people care about results and that pragmatism is essential — regardless of your political affiliation, you still have to pick up the garbage. He quotes longtime Jerusalem major Teddy Kollek as saying, “If you spare me your sermons, I’ll fix your sewers.”

“There has never been a mayor of a major U.S. city who has gone on to be president,” Barber said. “This goes back to the character of leadership. These aren’t charismatic leaders who can move millions of people through ideological statements and great rhetoric. These are very effective problem solvers and they will tell you that they lack the power to do anything without collaboration.

“Public-private agreements at a national level come with these big ideological questions, but those kinds of deals are second nature to mayors everywhere. This means that most mayors who are extremely successful don’t go on. Bloomberg started as a Democrat, then became a Republican and is now an independent.”

Barber thinks a convening of a global parliament of mayors that didn’t make laws so much as present best practices and experiments or goals for cities to voluntarily comply with could be very beneficial in fighting climate change. He says he’s spoken to a number of mayors that like that idea and are already holding informal meetings.

A possible precursor to this idea is C40, a network of the world’s megacities taking action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Created in 2005 by former Mayor of London Ken Livingstone, Bloomberg is currently the chair of the group.

After Hurricane Sandy, Bloomberg said of climate change that, “Cities are on the frontline because federal, national and international organizations aren’t doing anything. They either deny that the world is changing or they say that it’s not changing so fast that we should do anything about it but all of the scientific information that we have and the empirical evidence that we see…these are things that somebody’s got to worry about.”