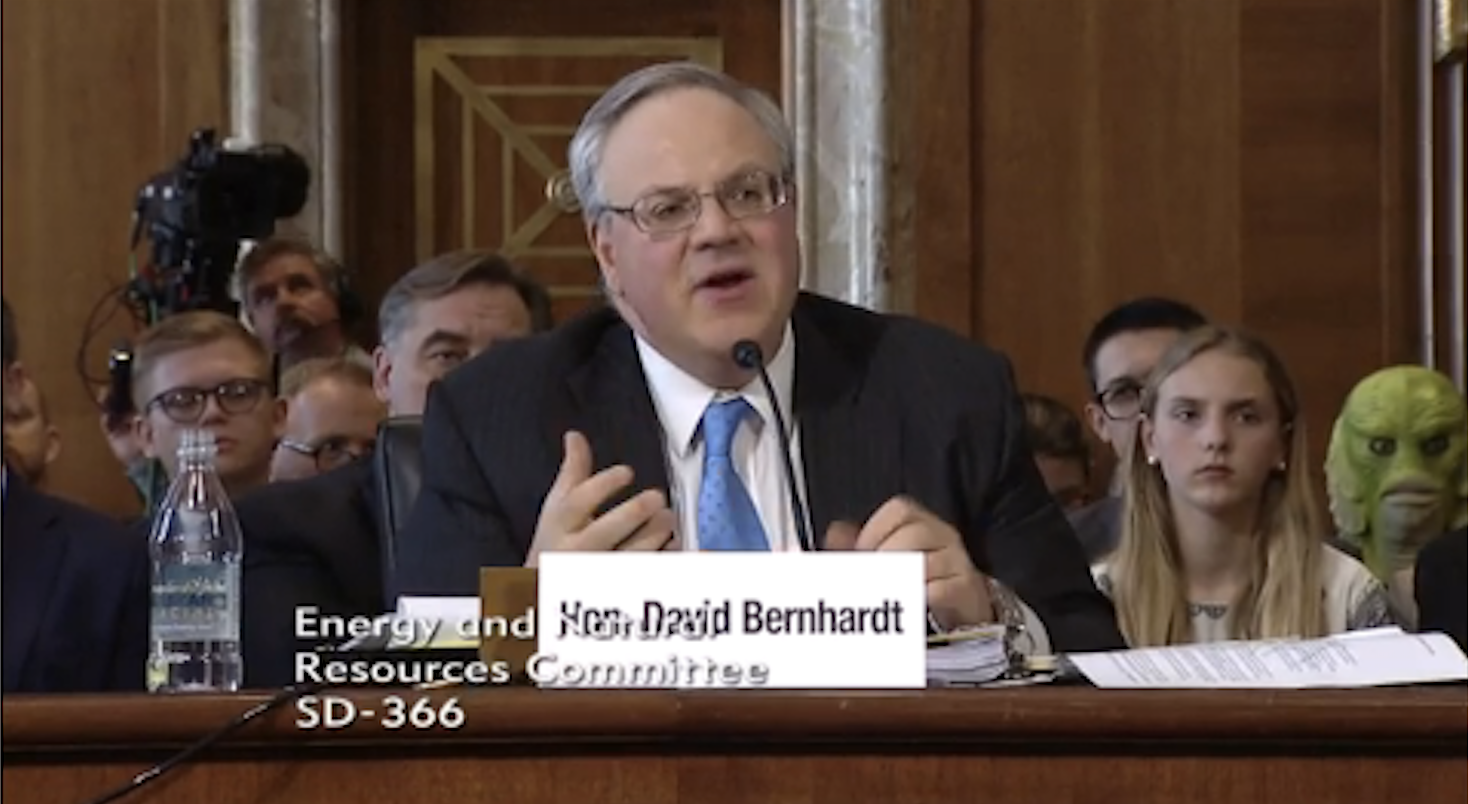

David Bernhardt, the former lobbyist nominated by President Donald Trump to lead the Interior Department, has been referred to as the “ultimate D.C. swamp creature” so frequently that a swamp creature was spotted in the audience for much of his confirmation hearing Thursday.

Lawmakers focused on Bernhardt’s conflicts of interest and reports of favoritism toward his former clients, including the fossil fuel industry, throughout the hearing.

“Mr. Bernhardt, I’m not claiming you are Big Oil’s guy, the Big Oil lobbyists are making that claim,” Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR) said during the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources hearing to consider Bernhardt’s nomination.

Wyden was referring to leaked audio released earlier this week in which oil executives are heard laughing at the level of access they have to the Trump administration. Specifically, the Independent Petroleum Association of America’s chief executive, Barry Russell, spoke about his ties to Bernhardt, saying it “worked out well” that Bernhardt had become the deputy secretary of the Interior Department.

Bernhardt was confirmed as deputy secretary in July 2017. Since then, he has been credited as the mind behind many of the Interior Department’s controversial policy changes — from selling off public lands to altering the Endangered Species Act. Trump announced Bernhardt’s official nomination to lead the agency earlier this month, but he’s been in an acting role since the previous secretary, Ryan Zinke, left at the end of last year, dogged by scandals and investigations.

Before joining the Interior Department, Bernhardt ran the natural resources department at lobbying and law firm Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck. During his time there, he worked on behalf of oil and gas companies as well as large agribusinesses to weaken environmental protections. Prior to that, he worked under President George W. Bush as solicitor at the Interior Department; his time was marked by scandal and ethics violations.

Now back at the agency under Trump, Bernhardt’s ethical issues have taken center of stage. He has so many potential conflicts of interest to avoid that he carries around a card listing all of them so he doesn’t forget. A recent analysis by the Center for American Progress found that Bernhardt has more conflicts of interest than any other Trump cabinet nominee. (Editor’s Note: ThinkProgress is an editorially independent news site housed at the Center for American Progress Action Fund.) In recent weeks, Democratic lawmakers have criticized Bernhardt’s lack of transparency regarding his schedule after he refused to release it publicly.

The first question posed to Bernhardt from committee chair Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) zeroed in on how he will handle these ethical issues and potential conflicts of interest. Bernhardt asserted that he has “actively sought and consulted with” ethics officials, adding, “I know how devastating it is when folks at the top behave in an unethical manner.”

However, this was quickly countered by Wyden who recounted a recent exchange he had with Bernhardt. Wyden said Bernhardt came to his office to assure the senator that he took ethics concerns seriously. Shortly after this visit, however, the New York Times revealed documents showing Bernhardt intervened to block a study showing pesticides might threaten the existence of 1,200 endangered species; Bernhardt has a history of lobbying against the Endangered Species Act.

“The decision to block the release of the report represented a victory for the pesticide industry, which has industry allies and former executives sprinkled through the administration,” the Times reported.

“So, you asked to come to my office to tell me your ethics are unimpeachable, but these brand new documents I saw make you sound like just another corrupt official,” said Wyden. “Why would you come to my office to lie to me about your ethics?”

Bernhardt replied simply, “the news article you’re referring to is not even close to the actual story.” (Later, Bernhardt reiterated for the record, “I certainly didn’t lie to the senator.”)

Throughout Thursday’s hearing, Bernhardt’s repeated favoritism for the fossil fuel industry was called into question. Regarding the administration’s energy dominance policy, Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto (D-NV) noted that “it appears that policy extends to oil and gas but it doesn’t extend to other forms of energy development on public lands such as solar, wind, and geothermal.”

She then listed a series of decisions and regulatory rollbacks made by the department “that imply your support more so of the fossil fuel industry.” This includes opening up national monuments to allow oil, gas, and coal leasing, rushing to allow an oil and gas lease sale in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, repealing safety rules put in place after the BP Deepwater Horizon disaster, and recalling furloughed workers during the recent government shutdown to continue processing oil and gas leases.

“Why hasn’t the department given the same level of intensity to cleaner forms of energy development than it is to fossil fuel development?” asked Cortez Masto.

“I really appreciate the question,” said Bernhardt. “I don’t think I can name a policy where we’ve not treated, for example, solar or wind, equally fairly.”

Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV) pressed Bernhardt on whether he would extend his ethics recusal beyond the required time limit, set to expire soon, “since you’ve had so many of your clients [who are] going to be working directly with this agency?”

Bernhardt said no. “I’m basically handcuffed if I am recusing myself,” he said. “I don’t really think that’s the best strategy.”

Later, Murkowski noted that Interior ethics officials found that should Bernhardt be confirmed, he will be in compliance with ethics rules and conflicts of interest law.

That finding did little to diminish the skepticism of some lawmakers. As Wyden argued, he sees only two possible paths forward with Bernhardt should he be confirmed to lead the agency: Either he continue making decisions that will favor the fossil fuel industry and his former clients, or “you disqualify yourself from so many matters I don’t know how you’re going to spend your day.”