Congress is trying to pass legislation that addresses the opioid crisis in an election year, so they’re moving fast, passing a bill through committee Thursday that would free up Medicaid dollars for opioid addiction treatment in institutionalized care. But it could be more harmful than lawmakers realize.

Rep. Greg Walden (R-OR) is aiming for the House to take up legislation in June. So to keep with schedule, the House Committee on Energy and Commerce — on which Walden serves as chairman — advanced 32 bills on Thursday, after unanimously advancing another 25 bills last week. The Senate health committee passed its legislative package in April.

While lawmakers agree it’s critical to address an epidemic where more people died of a drug overdose in 2016 than the aggregate of the Vietnam War, they don’t always jibe on how.

A question some lawmakers and journalists often ask is whether Congress is too closely targeting opioids, as the epidemic is a problem of polydrug misuse. Bloomberg’s editorial board warned “lawmakers need to take benzodiazepines seriously, before it’s too late.” (Overdose deaths associated with benzodiazepines are fewer than opioids, but still eight times what it was in 1999.)

“I’m concerned that here in Congress we’re so focused on opiates as the drug de jure, if you will, and that in five years or so when this crisis ends or abates or tapers that we’re going to have a bunch of federal programs that are specifically aimed at a problem that may not be as significant,” said Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) in April.

This point was raised again on Thursday when House members debated, largely along partisan lines, whether to advance the bill to allow Medicaid dollars to be used for opioid addiction treatment in certain treatment facilities.

“With 115 Americans dying each day, we have to focus on the opioid crisis,” said Rep. Mimi Walters (R-CA), the bill’s sponsor. “While we agree that all substance use disorders are important, we’re prioritizing our resources to address the opioid crisis.”

Walters was immediately met with resistance from Democrats.

“I’m troubled that this bill would expand treatment only to people with opioid use disorder as opposed to those with other substance use disorders like alcohol, crack-cocaine, methamphetamine,” said Rep. Jan Schakowsky (D-IL). “This bill is not only blind to the reality faced by people suffering from substance use disorder but it’s also discriminatory.”

Given that the bill exclusively helps those struggling with opioid use disorder, lawmakers are making it clear they only care when white constituents are dying, said Rep. Bobby Rush (D-IL).

“Too often, Mr. Chairmen, this committee and this House have paid attention to issues only when they affect the majority — the majority of the white population,” said Rush. “This leaves too many Black Americans behind.”

The measure would partially and temporarily repeal Medicaid’s Institutions for Mental Disease (IMD) exclusion, meaning it would allow federal Medicaid dollars to pay for opioid use disorder treatment up to 30 days in facilities with more than 16 beds. It would only repeal the ban until December 2023.

Currently states seek federal permission, by waiver, to relax the IMD exclusion for substance use disorder (SUD) treatment. Ten states have these waivers, with California being the first in 2015 to get the okay from the Obama administration.

“We don’t yet know what the utilization of this service looks like, as the program is so new, but it’s worth noting that the IMD exclusion exemption in California’s program is just one piece of a larger system,” said senior program officer at the California Health Care Foundation Catherine Teare, who worked extensively on the state’s waiver. “It’s not specific to opioids or any other particular substance, and it’s embedded within a system that provides access to a full continuum of evidence-based SUD services — based on the American Society of Addiction Medicine criteria.”

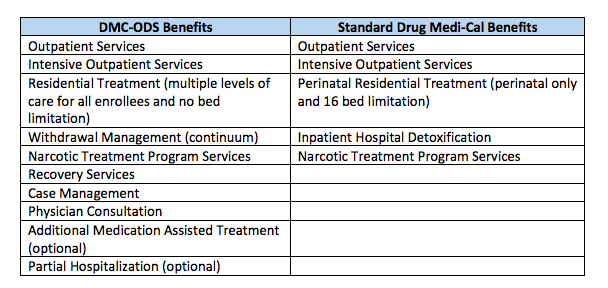

Sometimes that care is residential, and sometimes it’s not. People might start their recovery process in inpatient rehab, but then need community-based services to maintain sobriety. In 11 California counties, Medicaid not only pays for residential treatment but a host of other services:

It also forced relationship-building between primary care, mental health, and substance use treatment providers.

This is another reason why health experts are wary of Walters’ bill.

“I’m fine with paying for the residential component of care, but only if linked to an enduring care plan, such that a person would get more than that,” said Keith Humphreys, a drug policy expert at Stanford University. “Otherwise I think we’ll just spend a lot of money on expensive inpatient stays that don’t have any follow-ups, and the history of that is it’s actually worse than nothing because a person loses their tolerance and they’re even at a higher risk for overdosing than they were when they started.”

It just doesn’t work to build a system where people cycle in and out of institutions, Humphreys added.

Various Republican lawmakers pointed out during the hearing on Thursday that it took months for states to get the federal government to approve their waivers — which is concerning given how many people die a day on average from drug overdoses. For example, West Virginia applied in December 2016, but didn’t get approved until October 2017. For that, Republicans reasoned it just makes sense to lift the ban altogether.

But it’s also important to remember that Congress only has a limited amount of money dedicated to this drug crisis, and IMD repeal could be expensive.

“The cost of inpatient care typically ranges from $6,000 for a 30-day program to $60,000 for 90-day programs, while community-based outpatient services cost around $5,000 for three months of services. That means that any repeal of the IMD would require significant offsets,” according an analysis by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP). Experts at CBPP don’t support a repeal.

Repealing #Medicaid's restriction against payment for institutional #SUD care, known as the "IMD exclusion," would not solve the #opioids epidemic — it would risk worsening care for people who need treatment. @JudyCBPP and I explain: https://t.co/vslfeiZzl6

— Hannah Katch (@hannahkatch) April 17, 2018

The Congressional Budget Office is reportedly working on a score for the bill, but a GOP committee aide told Modern Healthcare that the agency has said repeal is in the “low single digit billions.” IMD exclusion for both mental health and SUD services without day limits would cost up to $60 billion over 10 years.

The worry is money will go to measures that further fragment care for people with substance use disorder, rather than investing in the continuum of care model. Alternatively, for states to secure a SUD waiver, they need to show how inpatient and residential care will supplement community-based services. This can work really well, just look at Virginia.

The House Committee on Energy and Commerce did pass several measures that seem small, but could do a lot of good. Some even addressed fentanyl, which is now the dominant cause for drug overdoses, with fentanyl-laced cocaine potentially becoming the next wave of the opioid crisis. For example the STOP Fentanyl Deaths Act of 2018 authorizes grants for federal, state, and local agencies to create or operate public health laboratories to detect the illicit, synthetic opioid.

Humphreys’ advice: Congress should pass targeted bills addressing the supply side of opioids — but aim for more comprehensive bills when it comes to treatment.