Over the last decade that Floyd Parks has been homeless in New York City, he hasn’t just had to endure the suffering that can come without a place to call home. He’s also had to endure being “arrested, humiliated, and abused by police officers,” he said.

In one incident, he was sleeping in an area he said he was told that he was allowed to occupy when police officers showed up with garbage trucks. They seized all of the shopping carts that Parks and other homeless people were using to store their belongings, he said, and threw them into the trucks without giving anyone the chance to recover their belongings first. “Like we’re nothing,” he said.

In that sweep, Parks said he lost not just all of his clothing, but also all of his identification — including his birth certificate and Social Security card, which can be difficult to get back. Without ID, he risks even more negative run-ins with police. “A cop can come ask for ID, and if I say no I get locked up automatically,” he said.

Another time, he was asking someone for spare change when the police came through doing a sweep of all homeless people in the area, he said. He was charged with aggravated panhandling, accused of blocking traffic and reaching into people’s cars, charges he denies. But he still spent four days in jail. That kind of incident “holds us back,” he said, “the mental state of mind.”

“I need to be treated with respect and dignity, not like trash on the street.”

“We are humans, we are individuals,” he said, anger vibrating in his voice. “I am a human being, I need to be treated with respect and dignity, not like trash on the street.”

There are hundreds of thousands of homeless people like Parks across the country: According to the government’s latest official count, there were 564,708 homeless people on a given night last year, 173,268 of whom had no shelter. And this report often undercounts the extent of the homeless population.

Yet many places have turned to punitive measures to deal with this crisis, employing tactics that criminalize homeless people’s behavior rather than focusing on ways to get people the help they need. According to a new report published on Tuesday by the National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty (NLCHP), laws that punish the homeless for the very things they do to survive have increased in every category it tracks over the last decade.

Examining the policies of 187 cities, the organization found that “laws punishing the life-sustaining conduct of homeless people has increased in every measured category since 2006.”

One of the most difficult tasks homeless people face is finding a place to sleep. As rents have risen, subsidies to help people afford them have declined. The number of families with children who get federal help paying their rent has fallen 13 percent since 2004, for example, reaching the lowest point in more than a decade. Yet rents are rising at a 3.5 percent annual rate amid the highest demand for rental housing since the 1960s mixed with sluggish growth in housing stock that isn’t keeping up. There is a shortage of 7.2 million affordable rental units across the country. Many families are thus thrust into homelessness when they can’t afford housing.

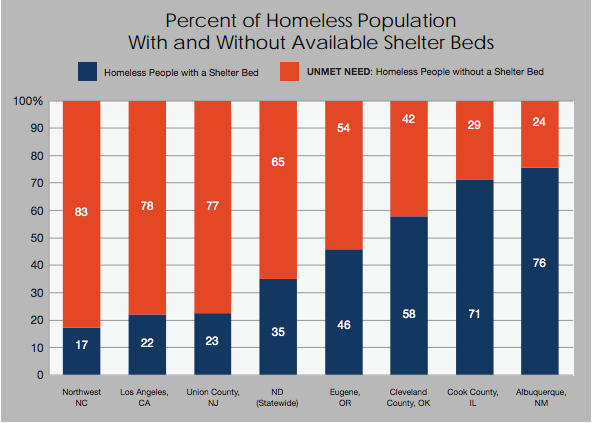

At the same time, finding space in a shelter can be nearly impossible. “Across the country, there are fewer shelter beds than homeless people, and shelter is at, or even over, capacity,” the NLCHP’s report notes. As one example, there is a deficit of 26,000 shelter units in Los Angeles County compared to its homeless population. And even when beds are available, many shelters’ rules and restrictions keep people out, while some may not feel safe in shelters that can be rife with violence or dangerous living conditions.

So most homeless people have no good options at night. Yet cities have made life even harder for them.

According to NLCHP’s research, bans on camping throughout an entire city increased by 69 percent since 2006, and blanket bans on sleeping in public have also shot up by 31 percent. Some homeless people may try to take refuge in a car, but cities have moved to crack down hardest on this option: bans on living in vehicles are up 143 percent.

Today, a third of the country’s cities ban camping in public, nearly one in five ban sleeping in public, and nearly 40 percent ban living in a car.

“Although many people experiencing homelessness have literally no choice but to live outside and in public places, laws and enforcement practices punishing the presence of visibly homeless people in public space continue to grow,” the report says.

The homeless must also do what they can to survive, and while some can access food banks or soup kitchens, others rely on panhandling or the kindness of strangers. Yet this, too, has become increasingly illegal. Bans on panhandling are up 43 percent, such that over a quarter of cities prohibit it. Six percent of cities restrict the ability for a good Samaritan to hand out food to the homeless.

The homeless don’t just suffer when night falls; many have nowhere to be during the day, particularly if shelters don’t open until the evening. Yet bans on sitting or lying down in public have increased 52 percent among the country’s cities, and bans on loitering or vagrancy have shot up 88 percent. Altogether, nearly half of cities ban sitting and lying in public while about a third prohibit loitering.

Stories like Parks’ are common in New York City. One day when Philip J. Malebranche, another New Yorker who was homeless up until finding a room to rent in June, was eating a sandwich in a public park at dusk, an officer came up to him and gave him a summons for being there after hours. “He thought it was dark, I thought it was light,” he said. While a judge eventually dismissed the summons, these kinds of run ins shake him. “I have a clean record, I don’t want to have a record,” he said.

The troubles have even followed him into shelters. One day three years ago, at 5:30 in the morning, he heard a knock on his door while he was brushing his teeth. When he opened it, three uniformed officers confronted him. They told him to go with them and even handcuffed him. Eventually he learned that they had conducted a sweep for anyone with outstanding summonses in the shelter, even though he says his had been dismissed.

“It was a waste of taxpayer money,” he said. And while a judge eventually dismissed him, the run in could have significantly set him back. He had to miss a day of work at his temporary city government job.

The incident stays with him. “An innocent person being taken in handcuffs… It’s traumatic,” he said.

These cities that have taken a punitive approach may not realize that it comes with a cost. But there is plenty of evidence that it’s expensive. In Colorado, a state whose cities have collectively passed 351 anti-homeless ordinances, aggressive enforcement comes with a big price tag: just six cities spent more than $5 million over the last five years through the police, courts, and incarceration.

The federal government has also warned that this approach could be unconstitutional and may soon cost states federal money.

A more cost effective approach, research has found, is helping the homeless get into housing. In Florida, it costs $31,065 per chronically homeless person for every year they live on the streets, but just $10,051 to give them somewhere to live with support services. San Francisco found that it spent 9 percent less on supportive housing and services than before it helped the homeless moved into housing, and costs continue to decline. Charlotte, North Carolina found that a supportive housing complex saved the city $1.8 million.

Some of the homeless have also been fighting back against practices that criminalize their daily lives, filing lawsuits against their cities. Parks is part of one such lawsuit brought by Picture the Homeless, an organization he works with.

“Because I am homeless, I have no key to the door,” he said, and he’s been treated like “a third class citizen.”

“We’re homeless, we’re not robbing, stealing, or killing,” he added.