Health reform advocates like Karen Pollitz have long argued that the affordability measures in the House bill would not adequately protect Americans “from excess financial burdens” and in today’s Kaiser Health News, Jordan Rau explains why. As it turns out, lower and moderate income families who actually use their health insurance or have a medical emergency, would face the same onerous costs that today’s under-insured population grapples with.

Under the House proposal, people receiving government subsidies could still end up spending 20 percent or more of their annual incomes on premiums, deductibles and co-insurance, according to estimates prepared by the House Committee on Ways and Means and obtained by Kaiser Health News. That financial load could grow substantially if the proposal’s financing — $1 trillion over a decade — is pared back as congressional leaders come under pressure to reduce the legislation’s costs.

The Democrats lowered the affordability standards to win over Blue Dog support in July and cushioned some of the cuts by placing a lid on the rate of premium increase (premiums cannot increase faster than 150% of medical inflation). The agreement requires families at 150 to 200% of federal poverty to spend a higher percentage of income on health care before receiving government assistance. Families with incomes at 400% of the federal poverty line (around $88,000 a year for a family of 4) would have to spend some 12 percent on health care before receiving government subsidies, a far higher percentage than what affordability experts consider appropriate. Add deductibles, co-insurance and other out of pocket expenses and you quickly find yourself spending 20% of income on health care (today, a middle-income family with individual coverage spends on average 22 percent of household income on health care).

Researchers argue, however, that families that spend more than 5–9% of their gross income on health care begin confronting affordability problems. As Karen Pollitz points out, “depending on what premiums are charged for qualified health benefit plans” subsidies capped above a certain level “may prove to be insufficient to ensure affordable health care for all Americans.” She suggests that Congress should “consider instead a rule that no individual or family will have to pay more than 10 percent of income on health insurance premiums…cutting subsidies off entirely at an arbitrary income level can leave families vulnerable,” she says.

But robust affordability measures are expensive — they make up the majority of the cost of the bill — and thus unpopular with politicians who ignore the White House’s repeated assurances that reform will be fully paid for without adding to the deficit. If they want effective reform, Democrats should be less afraid of big numbers and more concerned about ensuring that every family can afford comprehensive coverage. They should identify the necessary provisions for effective health reform first, rather than setting an arbitrary number and then stuffing it with watered down and ultimately ineffective affordability measures.

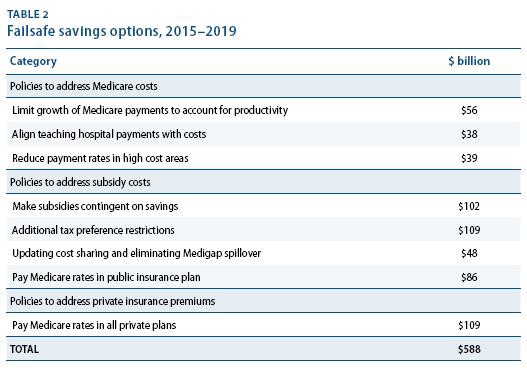

After all, policy makers can design legislation that guarantees a deficit neutral bill with better affordability measures. In fact, if the pay-fors of health care reform — productivity improvements, investments in health information technology and payment system reforms — fail to pay for the cost of reform, Congress could trigger certain ‘failsafe’ proposals:

A commission would monitor health care spending and implement a series of measures to address the problematic areas. This way, we can afford to pass adequate reform in which every American can purchase affordable health care coverage.