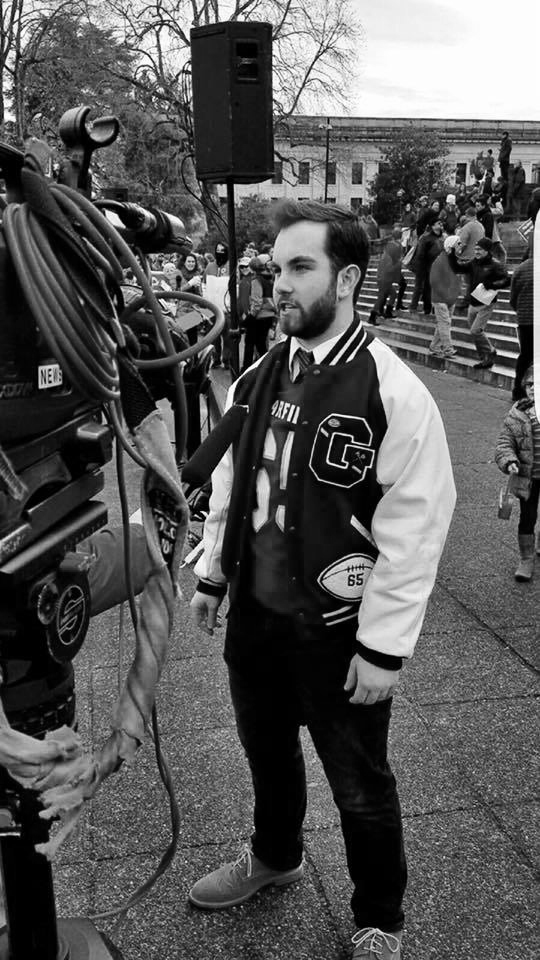

very morning, when former NFL player and current high-school football coach Joey Thomas walks into the recreation center at Garfield High School and heads to his office in the boys’ locker room, he passes by a colorful collection of inspirational quotes painted on the walls. Many of them are fairly typical motivational sayings in student-athlete environments – such as a “Pyramid of Success” extolling virtues like determination, loyalty, and hard work. But there’s one that stands out from the rest.

very morning, when former NFL player and current high-school football coach Joey Thomas walks into the recreation center at Garfield High School and heads to his office in the boys’ locker room, he passes by a colorful collection of inspirational quotes painted on the walls. Many of them are fairly typical motivational sayings in student-athlete environments – such as a “Pyramid of Success” extolling virtues like determination, loyalty, and hard work. But there’s one that stands out from the rest.

”The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort, but where he stands in times of challenge and controversy.” – Martin Luther King Jr.

Thomas and his Garfield Bulldogs players haven’t known a lot of comfort over the past year, ever since the team decided as a unit to take a knee during the national anthem before a football game last fall, joining former San Francisco 49ers’ quarterback Colin Kaepernick’s movement against systemic racism.

The team members thought they understood the possible ramifications of their actions that day. But they were wrong.

“Nobody knew it would be like this,” Thomas told ThinkProgress one hot July afternoon this summer as he prepared for practice.

The last year has been a whirlwind of cameras and interviews, death threats and hate mail, meetings with police and legislators; there’s even been pushback in the form of a recruiting scandal that Thomas believes surfaced in part due to the animosity towards the protest by some local leaders and journalists. The backlash has been overwhelming, but there’s been significant support — and, perhaps more importantly, progress — too.

Thomas, a fit 37-year-old with an infectious grin, a charismatic command, and boyish charm, doesn’t have regrets. But he’s not in the business of sugar coating, either. He knows the fight is far from over.

Dressed in black sweatpants and a black hoodie, Thomas grabbed cones and a football as he maneuvered his way through the empty Garfield hallways, following the faint echoes of shouts coming from the football field. When he arrived at the field, about a dozen players came barreling toward him, and he expertly – almost magically – guided them to gather around him in a circle and listen to what he was about to say. It became clear quickly that this wasn’t about to be a typical summer workout speech.

“I just want you to know, tomorrow morning, there’s going to be something else in the Times about me,” Thomas said. They were coming after him again.

elani Howard, a star basketball and football player at Garfield High School, was just beginning his senior year when he saw the news that Colin Kaepernick wasn’t going to stand during the national anthem. At first, he didn’t really understand.

elani Howard, a star basketball and football player at Garfield High School, was just beginning his senior year when he saw the news that Colin Kaepernick wasn’t going to stand during the national anthem. At first, he didn’t really understand.

Then he heard Kaepernick explain himself in his own words.

“I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of color,” Kaepernick told reporters. “To me, this is bigger than football and it would be selfish on my part to look the other way. There are bodies in the street and people getting paid leave and getting away with murder.”

Racial injustice is nothing new for Howard. He’s been stopped by police just for hanging out with his friends; at school, he’s noticed that his teachers are often surprised when he gets good grades.

“That’s not fair, because if a white person gets a good grade they expect them to do it. But if I do it, it’s a shock,” Howard said.

He doesn’t remember exactly who on the football team first brought up taking a knee, but he does remember the deep conversations he had with his teammates about the decision. He had been paying particular attention to police brutality and systemic racism since Mike Brown’s death in Ferguson, Missouri. He soon found himself leading conversations with his teammates about discrimination, Kaepernick’s message, and the third verse of the national anthem.

“In the national anthem, the third verse is about them killing slaves,” Howard said. “I didn’t know that until [Kaepernick] said that. I was like, ‘Wow I’m really standing up for a song that’s talking about killing my people.”

homas teaches sociology at Garfield, and in the morning, his class is full of his football players. He prides himself on being honest and straightforward with the kids — really teaching them about life. One morning, he remembers, they were talking about Beyoncé and Rihanna when one student asked, “Coach, what do you think about Kaep?”

homas teaches sociology at Garfield, and in the morning, his class is full of his football players. He prides himself on being honest and straightforward with the kids — really teaching them about life. One morning, he remembers, they were talking about Beyoncé and Rihanna when one student asked, “Coach, what do you think about Kaep?”

He turned the question back around: “What do you think?”

It sparked a discussion. Some students supported the protest; others thought it was stupid. One student said that Kaepernick was taking a knee because of the national anthem’s words. So they read the national anthem out loud — including that largely forgotten third verse.

“It opened up a dialogue,” Thomas said. “We have white kids, Asian kids, black kids, we have kids… from everywhere. Very diverse. It’s more minorities than not, and the conclusion was that verse is not for us, this song is not for us, and how can they say it’s the land of the free and the home of the brave, when that doesn’t apply to us?”

The conversation didn’t end that morning. But at football practice that evening, there seemed to be a consensus.

“All I did was give them a platform to voice their opinion,” Thomas said. “I gave them some positive steps, pointed them in a constructive direction, and they decided to kneel.”

uncan King, a Bulldog senior, was skeptical when he first heard about Kaepernick’s protest. He wondered, What does kneeling really do? What action are you going to take?

uncan King, a Bulldog senior, was skeptical when he first heard about Kaepernick’s protest. He wondered, What does kneeling really do? What action are you going to take?

On the bus ride to the game during which his teammates were planning to kneel, King was still uncertain about whether or not he would take a knee. He knew his teammates would understand his decision as long as he stepped back from the line respectfully, allowing others to take a knee and place a hand on the shoulder of the player in front of them – the most important thing was keeping that chain unbroken.

When the anthem began to play, King found himself sandwiched between two big offensive lineman whom he considered good friends. In that moment — even though he wasn’t aware of exactly why he was doing it — he took a knee right along with them.

It wasn’t until much later that evening, when he was alone after the game, that his decision became clearer to him.

“What drove me to do it was that they felt compelled to do it,” King said.

“We’d been told beforehand that if we did this, refs would be calling things against us, players would be gunning for them, other coaches were going to attack them,” he added. “The fact that they knew the consequences and felt that they had to take a knee anyways, that was so incredibly powerful to me that I knew I had to support them and I had to be a part of that.”

King’s support for the movement only grew as he and his classmates continued to have tough conversations over the next several weeks. That’s when he heard more about how his black teammates had lost family members to the criminal justice system; how they’ve never felt safe around cops; how it wasn’t just about police violence, but about a bigger system that wanted them to put their bodies and minds on the line on Friday night to sell tickets, but then didn’t want to treat them as equals during class on Monday.

he Garfield football team’s decision to kneel together made national headlines. Within weeks of the first protest, their photo was included in the October 2016 Time Magazine issue that featured Kaepernick on the cover, and Kaepernick himself said he thought the Bulldogs’ solidarity was “amazing.”

he Garfield football team’s decision to kneel together made national headlines. Within weeks of the first protest, their photo was included in the October 2016 Time Magazine issue that featured Kaepernick on the cover, and Kaepernick himself said he thought the Bulldogs’ solidarity was “amazing.”

As protests during the national anthem at sporting events began to spread across the country, they spread within the walls of Garfield, too.

The girls’ volleyball team began kneeling during the anthem. So did the marching band and the cheerleading squad. At the rest of that season’s football games, Garfield parents and the entire student section remained seated as the anthem played. During the national anthem at the school’s homecoming game, members of the Black Student Union held up a sign reading, “When we kneel you riot, but when we’re shot you’re quiet.” Garfield principal Ted Howard released a statement of support, saying the football team was a “catalyst for positive dialogue and change.”

One day in October, teachers and administrators at Garfield arranged to take a photo with the football and volleyball teams to show their support. As the student-athletes gathered for the picture, the faculty members present greeted them with a huge round of applause.

“I felt like the school and the community was behind us,” Howard said. “We actually had people that were behind us and not just people hating us.”

he Monday morning after the team first took a knee, Coach Thomas walked out of his front door and found his car sitting in his driveway with its tires completely slashed.

he Monday morning after the team first took a knee, Coach Thomas walked out of his front door and found his car sitting in his driveway with its tires completely slashed.

He had to call the school and tell the kids he wasn’t going to be at practice that morning. He also had to tell them why.

“I said, ‘Fellas, I’m not going to make it to practice, someone slashed my tires, they don’t believe in what we stand for — but if this is what I have to go through to stand with you guys, I’ll do it every day of the week,’” Thomas recounted. “‘You’re my guys, and if I have to go through hell for you, I’ll go through hell. But don’t be afraid. Stay the course. It’s all going to work out. I’m good, my family is good, everything is going to be all right.'”

Though he put on a brave face to the players, inside, he was terrified. This happened at his home. Where his family lived. He had three kids, and his wife was pregnant with their son.

ing’s family, which he describes as pretty liberal, was supportive of the football players’ protest. But they soon got a wake up call about what a risk it was.

ing’s family, which he describes as pretty liberal, was supportive of the football players’ protest. But they soon got a wake up call about what a risk it was.

King’s mom, who ran the Garfield football Facebook page, was expecting a handful of disgruntled fans in response to players’ decision to kneel. Instead, she got a barrage of death threats. Message after message was posted from adults across the country who said they wanted the teenagers on the Garfield football team — some as young as 14 — to go to prison or to die.

“you low life nothing more than a porch monkey hope the cops make your life hell sorry piece of black project raised welfare bum,” one message from Richard Tarter read.

King said his mother’s first instinct was to delete the messages, but Coach Thomas told her not to. He pointed out that, if people were willing to put their names on these public messages, they needed to be seen. This type of vitriol was, in many ways, proof — if anyone called the movement unnecessary, they could simply show them the people calling for the murder of 14-year-olds by name.

Perhaps that’s why King wasn’t as shocked as many Americans were when Donald Trump won the White House last fall. During the final days of the presidential campaign, he’d look at the hateful messages directed toward his teammates on social media, and remind himself that these people were likely voters too.

esse Hagopian, a teacher and activist at Garfield, has, like most black men, had plenty of uncomfortable encounters with police. He’s been pulled over when he was doing nothing wrong, approached at night while hanging out with friends, and asked inappropriate questions about his profession and intentions.

esse Hagopian, a teacher and activist at Garfield, has, like most black men, had plenty of uncomfortable encounters with police. He’s been pulled over when he was doing nothing wrong, approached at night while hanging out with friends, and asked inappropriate questions about his profession and intentions.

In 2015, after Hagopian gave a speech at a Martin Luther King Day celebration — one of the biggest social justice marches of the year in Seattle — he was on the sidewalk talking to his mom on the phone, trying to tell her where to pick him up so they could go to his two-year-old’s birthday party, when a police officer pepper sprayed him in the face.

I was pepper sprayed at the Martin Luther King day march. The milk is helping a lot. Wish we had a better world! pic.twitter.com/nWfFnejyfM

— Jesse Hagopian (@JessedHagopian) January 20, 2015

Hagopian’s encounter with police was caught on video, and it went viral. In response, Hagopian filed a lawsuit against the Seattle Police Department, who has been federally monitored under a Consent Decree since 2011 because of a documented pattern of unconstitutional and excessive force.

Seattle’s Office of Professional Accountability initially ruled in Hagopian’s favor and handed down a mild punishment for the officer who pepper sprayed him — a one-day suspension without pay. But the suspension was overturned by Seattle’s chief of police, Kathleen O’Toole, who praised the officer as a “stellar” employee.

As Hagopian’s legal challenge proceeded, the windows of his cars were smashed multiple times. His house was targeted with hate mail. And his young children were given a rude awakening — after all, it was hard to shield them from the truth when Hagopian had to spend his two-year-old’s birthday party in the bathtub, with his sister pouring milk on his face to try and calm the searing pain burning in his ear, nostrils, and eyes.

Eventually, largely thanks to the video proof, the city ended up settling with Hagopian for $100,000, though Seattle officials did not admit any wrongdoing in the settlement.

“You don’t know where those kind of encounters end. So it’s terrifying, when you’re out at night by yourself. These are the experiences of black communities,” Hagopian said. “That’s why when Kaepernick took the knee, it was just like a dam bursting, like finally somebody with prominence can express what all of us are thinking — that there isn’t justice. Why do we have to pretend like there is, over and over again?”

eattle is progressive, yes, but it’s also predominantly white. The tech boom in Seattle is leaving people behind; often, teachers don’t make enough money to afford to live in the districts where they teach. There are about 4,000 homeless students in Seattle Public Schools. Meanwhile, Seattle has two of the five richest people in the world living in its city limits, Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos.

eattle is progressive, yes, but it’s also predominantly white. The tech boom in Seattle is leaving people behind; often, teachers don’t make enough money to afford to live in the districts where they teach. There are about 4,000 homeless students in Seattle Public Schools. Meanwhile, Seattle has two of the five richest people in the world living in its city limits, Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos.

“That’s a massive contradiction,” Hagopian said. “That’s just an obscenity.”

The education system in Seattle remains markedly segregated. Seattle has the fifth-largest testing gap between white and black students in America, and according to an investigation by the Department of Education, Seattle public schools suspend black students at four times the rate of white students for the same infractions.

Hagopian says these are the injustices that are really driving the activism at Garfield. The children see this. They’re not blind to reality.

Garfield was one of the first schools in Seattle to have a black student union. By 1961, the student body was over 50 percent black, despite the fact that the rest of Seattle was only 5 percent black. When Martin Luther King made his only trip to Seattle in 1961, he visited Garfield High School to deliver a speech encouraging creative protests to put an end to racial discrimination and segregation. One man who was in the crowd for that speech went on to found the first Seattle chapter of the Black Panther chapter a few years later. Jesse Jackson and Barack Obama have also given seminal speeches at the school.

“I didn’t know [Kaepernick’s protest] would spread to Garfield, but I guess, after it happened, I wasn’t totally surprised given the legacy of activism at our school,” Hagopian said.

arfield players didn’t limit their protest to the sidelines. They also got involved in their community. They released a six-point plan to address injustice and oppression, which focused on ensuring equality for all races, genders, classes, and sexual orientation; improving the media’s portrayal of people of color; ending academic inequality; ending segregation through classism; providing bias training for teachers; and fostering a public acknowledgement of institutional racism.

arfield players didn’t limit their protest to the sidelines. They also got involved in their community. They released a six-point plan to address injustice and oppression, which focused on ensuring equality for all races, genders, classes, and sexual orientation; improving the media’s portrayal of people of color; ending academic inequality; ending segregation through classism; providing bias training for teachers; and fostering a public acknowledgement of institutional racism.

With the plan in hand, the athletes spoke to youth groups about racial injustice, met with police officers about resolving some issues between the cops and communities of color, and were even honored by the NAACP with a dinner.

In January, the Garfield football team traveled to the state capital, Olympia, to talk to the Lt. Governor about enforcing the McCleary Act — a Washington State Supreme Court ruling in 2014 that directed the Washington legislature to appropriate adequate funding for public schools.

The state legislature has racked up more than $70 million in fines because of its failure to come up with a school funding plan that follows federal law and the McCleary Act. Despite the Garfield football team’s efforts, an adequate education budget still hasn’t been passed.

n 2016, Garfield had its best season in years under the tutelage of Thomas, amassing an 8-2 record while making front-page news across the country for their protest.

n 2016, Garfield had its best season in years under the tutelage of Thomas, amassing an 8-2 record while making front-page news across the country for their protest.

The headlines weren’t all positive, though. In March of 2017, a front-page Seattle Times article reported that Garfield High school was under investigation for alleged recruiting violations regarding a teenager from Texas, who says Garfield recruited him and flew him to Washington because of his athletic prowess. He was the third-string running back for Garfield that fall, and played in only six games, but the story reported allegations that Thomas had unlawfully recruited him to Garfield, paid for airfare, registered him as a homeless student so his grades wouldn’t impact his playing eligibility, and then dropped him when the situation got complicated.

Thomas denied the accusations, and in June, an independent investigation into the allegations yielded no evidence of any violations. He felt vindicated.

But the Times didn’t stop digging. Reporters continued to reach out to former and current Garfield students, and on July 22 — the day after Thomas warned his football players about what was coming — the Times published another big investigation about Seattle high schools like Garfield that abuse the “homeless” designation to keep top athletes eligible.

Thomas continues to maintain his innocence — and he also implies it’s not a coincidence that this negative news coverage put a spotlight on Garfield immediately after a season during which his athletes dominated opponents on the field, and led protests to draw attention to police brutality on the sidelines.

His players also feel Thomas was targeted. King was infuriated when he saw the Times investigation in March, with front-page photos of Thomas and Principal Tim Howard — both black men — cropped down to look like mug shots. King said he felt like the paper was trying to portray his coach and principal as criminals, simply because so many people felt offended by the protest.

“That made a lot of people angry,” King said.

Thomas thinks that if he were a white man, this would have played out differently. But that’s not the reality. “When you have minorities leading minorities, that’s scary,” Thomas said. “They don’t want that.”

ith his $100,000 settlement from the Seattle police, Hagopian started an annual Black Education Matters Student Activism award. Last year, Howard was one of the winners.

ith his $100,000 settlement from the Seattle police, Hagopian started an annual Black Education Matters Student Activism award. Last year, Howard was one of the winners.

“Most people know him as a celebrated athlete Garfield because he was on the basketball team and the football team. But I really knew him for the insights in my class,” Hagopian said. “And then to see him not only excel on the court and on the field, but to see him take on that leadership role, and help the team make a decision that had a real impact on our school, on our city, and even nationally — it was just really beautiful to see.”

Howard beams when asked about winning Hagopian’s award. He appreciated the money and the acclaim, of course. But what really left an impression on him was getting the chance to meet Michael Bennett — a Seattle Seahawk player and noted activist — at the award ceremony.

Since then, Howard has enrolled in college. He’s learned how to give televised interviews; he’s become a more confident public speaker; he’s figured out how to listen, to mediate, and to follow his convictions. He says these are the biggest lessons he took with him from high school — and they’re ones he predominately learned by taking a knee.

He encourages other teenagers to make their voices heard, too.

“Don’t be scared. Whatever you have to say, just say,” he said, when asked what advice he would pass down to younger students. “You feel like you’re wrong and you’re not wrong. And even if you’re a freshman, you can still speak up. …Doesn’t matter how old you are because you all have something smart to say.”

ing ended up being injured for part of the season, and didn’t play much. But he took a knee during the anthem every game, and he became one of the leaders of the team’s off-the-field activism.

ing ended up being injured for part of the season, and didn’t play much. But he took a knee during the anthem every game, and he became one of the leaders of the team’s off-the-field activism.

He wrote a powerful, award-winning essay for the Seattle Library Foundation about the experience, in which he described in detail the moment he first took a knee, and the teammates who inspired him to do so. He wrote that as the team lined up on the sideline just before the anthem began, the player in front of him, Israel, turned around and echoed the message the coaching staff had told them all on the bus ride to the game: “Do it with all your heart, or don’t do it all.”

Israel is huge. At well over six feet tall and near 300 lbs, he fits the bill of most high-profile police killings. He’s big, tall, strong, and black. All traits that make him far more likely than me to be the victim of police brutality.

His father is a preacher. He likes fishing on Lake Union. He made a promise to himself that he would never use curse words.

The young man behind me, with his massive hand firmly holding the back of my shoulder pads, goes by the nickname “Cookie.” His real name is Jeremiah. We often share a hug before a game. He loves my dog and always asks how he’s doing. He’s a father at only 16, and though he won’t admit, I fear he often fights serious depression.

Both are intelligent, funny, caring young men. Young men that in a post-racial America would only ever be seen as such. Young men that wouldn’t have suffered any injustices or grievances to compel them to kneel during the national anthem. But that’s not the America we live in, and those aren’t the lives they’ve lived.

After graduating from Garfield, King decided to attend Indiana University, where his fight for social justice continues. He donates to the NAACP. He wants to help bridge gaps in education and achievement; he hopes to start a program to allow privileged families to pay the AP testing fee for cash-strapped families, so that a lack of money doesn’t keep anyone from taking those classes or tests.

“When people start protesting, it’s time to start listening,” he said. “No matter what the cause. You’ve got to give it your ear. Then you can make a decision, but you’ve got to give it your ear because there’s at least something motivating that.”

ow do you measure the victory of a movement? How can you be sure that taking a stand is worth it?

ow do you measure the victory of a movement? How can you be sure that taking a stand is worth it?

These are the kind of questions that Mike Green, an assistant coach on the Garfield football team, has grappled with a lot. He grew up in this part of town. He knows multiple generations of families in the area. This is personal for him.

“These are my people, some way or another. So I’m invested,” he said.

While Green has seen staggering amounts of support for the football team’s decision to kneel, he’s also seen the ugly looks from classmates and heard the condescending tone taken by teachers who don’t support the players protesting. He’s worried about the negative potentially outweighing the positive. How will the criticism impact the players? Was the support they received within the school and from progressive groups in the community enough to help them weather the death threats, the negative press attention, and the never-ending controversies spurred by their actions?

There aren’t clear answers for Green’s questions. A movement can’t be quantified with a beaker or a ruler; marking progress isn’t as simple as checking accomplishments off a daily to-do list. As we’ve seen in the NFL this season — with the president repeatedly lashing out against players who choose to protest, owners panicking over their teams remaining in the national headlines, Kaepernick being blackballed from the league apparently as punishment for taking a stand, and players openly arguing over what progress looks like — it’s messy. Movements often are.

At Garfield High School, the protest movement started by Kaepernick opened eyes and changed hearts; it built activists and fueled hatred; it inspired crucial conversations and revealed ugly truths about where society is today. That kind of uneven progress won’t prompt national changes overnight. But it can help mold young adults, whose actions in turn create a ripple effect that ensures the impact will continue.

This past season — as Garfield made it all the way to the state semifinals, a momentous accomplishment for a program that had a losing record just a few years ago — the players didn’t all take a knee during every game. But Thomas continues to talk with them about racial inequality. He continues to push them to be involved in the community. And he continues to let them know that they, too, can make a difference.

“Did I believe in the cause? Absolutely,” Thomas said. “But more importantly I believed in our kids having a voice heard and knowing that they too are important and they can impact change.”

Visuals by Diana Ofosu.