Americans love to rank things. So lists of the best presidents in American history frequently allow historians to duke it out over whether George Washington, Abraham Lincoln or Franklin Delano Roosevelt should be remembered as our nation’s greatest leader. Meanwhile, recently departed President George W. Bush already ranks close to the top in polls of historians asked to rank the worst president in American history. Rather than wade into the thicket of which men best or worst served their nation during their time in the White House, we would like to offer a different kind of list. Here are five presidents who routinely rank far above what their performance in office deserves in surveys considering presidential performance:

1. Andrew Jackson

The Democratic Party frequently hosts Jefferson-Jackson Dinners honoring President Jackson and another historic president who is also on this list. It should reconsider this practice, as Jackson’s policy towards Native Americans was only a few steps shy of genocidal. In theory, President Jackson’s Indian Removal Act, permitted him to negotiate voluntary agreements with tribes in the southeastern United States encouraging them to exchange their eastern lands for new territory in the west. In reality, Jackson’s forced migration policy was anything but voluntary. By his last year in office, 46,000 Native Americans were removed from their lands, opening up tens of millions of acres to white settlement and slave-worked agriculture. As many as a quarter of the southeastern Cherokee people died of cold, hunger, and disease in the Trail of Tears march that began shortly after Jackson left the White House.

Beyond his indefensible treatment of Native Americans, it is ironic that Jackson’s face is now featured on the $20 bill, because he proved such a poor steward of the nation’s economy. Jackson waged war against the Second Bank of the United States, an early predecessor to the modern Federal Reserve, and he required federal land sales to be conducted in gold or silver. Historians disagree somewhat about the role Jackson’s retrograde monetary policy played in triggering the economic depression that began shortly after he left office. But there’s little doubt that, by taking away America’s ability to centrally manage its money supply, Jackson deprived his nation of a key tool it would need to fight off the looming depression. America would not have a central bank for most of a century after Jackson left office, and we paid the price for this fact. Today, banking panics are viewed as rare, disastrous economic events. Yet in the years that America had no central bank, according to Harvard Business Professor David Moss, we experienced more bank panics than any other industrialized nation — such panics occurred in 1837, 1839, 1857, 1873 and 1907.

2. Ronald Reagan

President Reagan ushered in the misguided era of massive deficits, bloated military spending and tax cuts for the very rich that America still struggles to this day to put to an end. Yet Reagan wrongly receives credit for the economic boom that began a few years into his presidency due to events entirely outside of his control. When Reagan took office, America faced double-digit inflation rates matched with a sharp spike in unemployment. Federal Reserve Chair Paul Volcker, a Carter appointee, chose to break the first problem by exacerbating the second — driving up interest rates in a successful effort to break inflation. When Volcker finally took the brakes off the economy and ended the recession he created by lowering interest rates back to more normal levels, housing and auto sales took off, the economy boomed back to life, and Reagan rode the undeserved credit to a second term in the White House.

As Rosalynn Carter once said, Reagan made America “comfortable with our prejudices.” Reagan infamously began the final leg of his presidential campaign by traveling to the Mississippi town where three civil rights workers were brutally murdered and proclaiming “I believe in states’ rights.” Reagan ignored the AIDS crisis for years. He gave us Justice Antonin Scalia. And he tried and failed to appoint another justice who once claimed that the federal ban on whites-only lunch counters is rooted in a “principle of unsurpassed ugliness.”

3. Woodrow Wilson

Unlike the first two names on this list, Wilson presided over a far more mixed legacy as President of the United States. Wilson created the Federal Reserve. He expanded federal anti-trust law. He signed a law effectively banning child labor, although it would eventually be struck down by a conservative Supreme Court. And his League of Nations formed much of the framework for the modern UN — even if Wilson could not convince his own nation to join the League.

Yet, for all of his accomplishments, Wilson belongs on this list because of his inexcusable record on civil liberties. Wilson’s Espionage Act criminalized the mere act of presenting conscripted men with arguments regarding why they should avoid the draft. And his Sedition Act went even further, banning “disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language” about the U.S. government, military or flag. Wilson was a racist who signed laws banning interracial marriage in the District of Columbia and segregating DC’s streetcars. And his elevation of Justice James Clark McReynolds ranks among the worst appointments to the Supreme Court in American history.

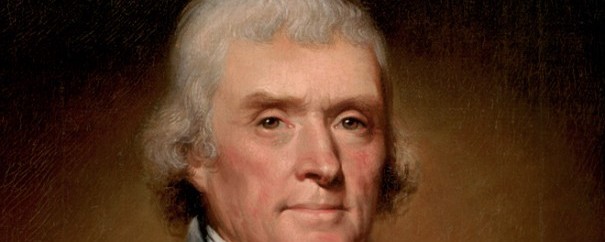

4. Thomas Jefferson

Like Wilson, Jefferson’s legacy is far more mixed than malign, as no one can question the significance of his contributions to American history — beginning with the document that declared us an independent nation. Yet Jefferson’s most important accomplishment as president was also the most important flip-flop in American history. During the Washington Administration, Jefferson led a losing faction seeking to constrain federal power to foster the nation’s economic growth far beyond the limits contained in the Constitution’s text. This narrow vision of the Constitution initially led him to oppose the Louisiana Purchase as president, although he eventually relented and doubled the size of the United States in the process.

Nevertheless, Jefferson’s initial view of the Constitution lives on in the modern tenther movement which would declare everything from Medicare to Social Security to national child labor laws unconstitutional, and it occasionally inspired future presidents to stand athwart American progress. President James Buchanan, who is widely viewed as among our nation’s worst presidents, raised Jeffersonian constitutional objections when he vetoed land grant colleges. President Abraham Lincoln, considered one of America’s greatest presidents, would later sign the same bill Buchanan blocked.

Additionally, while Jefferson may have written that “all men are created equal,” his actions did not match his words. Our third president held hundreds of slaves over the course of his lifetime, freed only a handful upon his death, and often engaged in the unspeakably cruel practice of punishing slaves by selling them away from their families and friends.

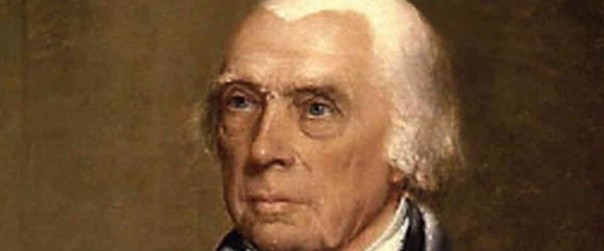

5. James Madison

Madison was another man of accomplishment who belongs on this list despite his tremendous contributions to his nation and to the world. Madison’s Bill of Rights formed the backbone of America’s single greatest export: the idea that a nation’s charter should embrace fundamental civil rights that cannot be abridged by government — although these rights would not be understood as limits on state governments until many years after Madison’s death. Like Jefferson, however, Madison also believed that we should ignore the text of the Constitution and impose limits on Congress’ power that, if they existed today, would make Medicare, Social Security and much of America’s educational infrastructure impossible. As president, Madison vetoed a bill to create new roads and canals, claiming that it violated the Constitution.

To his credit, however, Madison would oppose the efforts by modern conservatives to revive the least appealing aspects of his constitutional vision. Although Madison opposed the creation of the First Bank of the United States on constitutional grounds, he signed the bill creating the Second Bank, noting that “Congress, the President, the Supreme Court, and (most important, by failing to use their amending power) the American people had for two decades accepted” the First Bank. Unlike so many of today’s conservatives, Madison understood that he had no right to toss out decades of well-settled constitutional law just to satisfy his own pet theory.