Over the last few years, as California’s historic, four-year drought has intensified, scientists have found clues linking the extreme weather event to human-caused climate change. Now, a new study is the first to estimate just how much climate change contributed to the drought.

The study, published Thursday in Geophysical Research Letters, found that climate change can be blamed for between 8 to 27 percent of the drought conditions between 2012 and 2014 and between 5 to 18 percent in 2014. Though these relative contributions of climate change differ between the two periods of time, due to differences in severity of the drought from year to year, the study said climate change’s absolute contribution was “virtually identical” between the two periods — meaning climate change has contributed a fairly steady amount to California’s drought over the last three years.

To figure out how much anthropogenic warming contributed to California’s drought, the researchers looked at soil moisture data in various parts of the state for every month from 1901 through 2014. With the help of that data, “we know what the climate’s like in every month since 1901,” said Park Williams, assistant research professor at Columbia University’s Earth Institute and lead author of the study. “We are fairly certain as to how much precipitation fell in a given month in given location.”

Every year, the bully — or atmosphere — is demanding more resources — or water — than ever before

The researchers used that data to calculate how much water evaporated from the soil each month. When the researchers compared the data to climate models in California, Williams said, they were able to determine how much of the current drought could be blamed on climate change — an amount that, according to Williams, is likely closer to 20 percent than to 8 percent. Steadily rising temperatures due to climate change, along with natural weather variability in California, led to more and more water evaporating from the soil.

The researchers used four different methods to estimate global warming trends, and, for every month and every California location studied, calculated 432 possible soil moistures. That rich supply of data helped give the researchers a reliable range of climate change’s contribution to the drought, but the data was too complex to glean one single percentage from it.

“There is no one correct way to do this,” Williams said. “We can’t just ask the Earth exactly what’s been human-induced and what’s natural.”

The study does make it a little easier to illustrate how climate change and natural variability interact in a drought situation, however. Natural weather variability means temperatures, precipitation levels, and humidity are constantly changing — but they’re changing while the undercurrent of climate change steadily brings temperatures up. Climate change, Williams said, “is like a bully that demands part of your money every year, and every year it demands more of your money than the year before. Every year, the bully — or atmosphere — is demanding more resources — or water — than ever before.”

The bully, he said, “is breaking a record every single year and in a predictable way. We know in 2030 that the bully will be asking way more than it is right now. knowing that, we can be preparing more wisely in managing water resources to ensure that we can pay bully every year.”

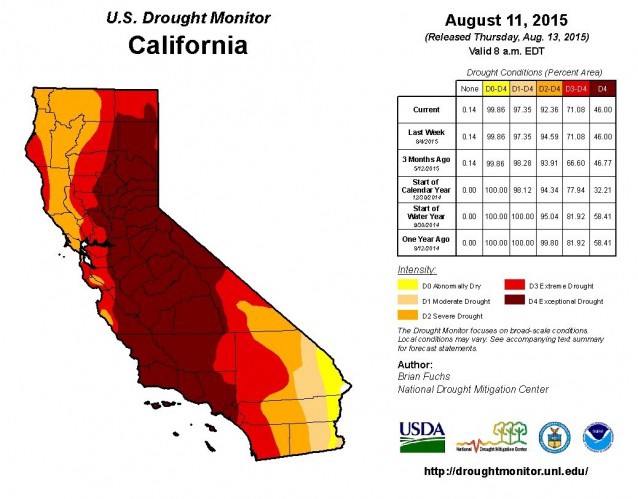

California’s drought has hit the state hard over the last four years, threatening its lucrative agriculture industry and leading to its first-ever mandatory restrictions of water use. The drought has broken record after record — in April, the state’s previous low-snowpack record was, in the words of California’s chief of snow surveys, “obliterated,” and temperature records have been broken multiple times already in 2015. It’s led to job losses in the agriculture industry, and according to one study will likely cost the state $2.74 billion this year — an increase over the $2.2 billion it cost last year.

Studies besides Thursday’s have assessed the drought’s severity and linked it to climate change. A study from 2014 found that California’s drought was the most severe the state has had in the last 1,200 years. And a Stanford study from this March concluded that the region of high atmospheric pressure — dubbed the “ridiculously resilient ridge” — above the Pacific Ocean that’s been blocking storms from making their way to California was more likely to form under today’s climate change conditions than it would have been if global warming hadn’t been occurring.

Thursday’s study “supports the previous work showing that temperature makes it harder for drought to break, and increases the long-term risk,” climatologist Noah Diffenbaugh, who led the Stanford research, said in a statement.

That finding from the study — that droughts like the one in California are becoming increasingly likely in many areas because of climate change — is one of the study’s most important conclusions, Williams said. According to the study, higher levels of evaporation — driven by higher temperatures — will overtake any increases in rain that California is expected to have over the next few decades.

“Severe drought years in California should occur 7 percent of time in warming-free scenario,” he said. “We now find that under the current amount of warming, the probability of a severe drought year has approximately doubled. So even though it may be argued that the human-induced part of the drought sounds small at 20 percent, it seems worse when you consider the probability of extreme drought has increased by 100 percent.”

Historically, it’s been difficult to tie a particular weather event to climate change. But Williams said he thinks it’s getting easier, as new and improved climate datasets continue to come out and as computational abilities improve. And he says it’s important to keep doing studies like this that aim to figure out just how much climate change influenced a major event. He said he’s heard claims, both from researchers and from the media, of two extremes regarding California’s drought: one, that it was caused entirely by climate change, and two, that it was caused solely by natural weather variability. Both those claims, Williams said, are “equally dangerous.”

“If all Californians believe that this drought is caused purely by natural variability, then they’re very unlikely to want to prepare for a trend towards increasing drought variability in the future,” he said. “If all Californians think this drought is caused purely by global warming, then when natural climate variability causes California to get wet in a few years, they’re going to be very surprised, and possibly prone to thinking that climate change is bogus. Knowing the true answer can allow for more educated decisions about how to prepare.”