Late last year, Canada’s prime minister, noted internet bae and progressive cabinet-appointer Justin Trudeau, approved two new tar sands oil pipelines. Not only did the move complicate the country’s efforts to reduce its greenhouse gas footprint, but it also paved the way for a pipeline project through northern Minnesota, through native treaty land, and through some of the only wild rice waters in the world.

Now, a rider on an energy omnibus bill, which must be signed to continue funding the state government, calls for circumventing Minnesota’s regulatory body and unilaterally approving a replacement project for Enbridge Energy’s Line 3—connecting one of the Canadian pipelines to U.S. refineries. Many say the rider, and a slew of others like it, are the Republican-controlled legislature’s attempt to do an end-run around the environmental review process, and environmentalists want to know why, amid a troubled oil industry outlook, lawmakers would seek to prop up an oil transmission project.

“You’ve got a Republican legislature that is daring a Democratic governor to veto a budget bill and shut down the government,” said the Minnesota Center for Environmental Advocacy’s Aaron Klemz.

The battle over Line 3

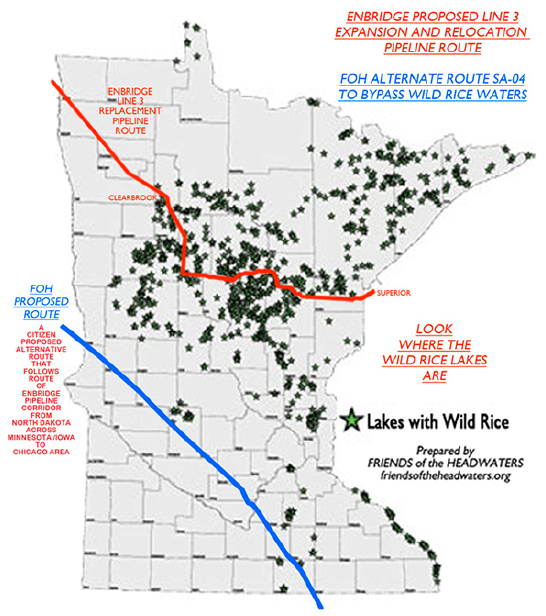

Over two years ago, Enbridge applied to the Minnesota Public Utility Commission (PUC) for a permit to relocate and expand Line 3, which runs from the Canadian border to refineries and a pipeline hub near Superior, Wisconsin. The expansion will allow Enbridge to transport more than twice as much oil through “Line 3.” (The new project is officially known as the Line 3 Replacement Program. The new pipeline will be called Line 3, even though it has a different route and a different capacity.) The 60-year-old existing pipeline is on its last legs. Enbridge was directed years ago to reduce pressure on the line, so it no longer operates at full capacity. And the company’s own records show 900 integrity “anomalies” — such as corrosion and seam cracking — on the old line.

To help move things along, state representative Pat Garofalo (R) recently attached a rider to the state’s omnibus energy bill that would immediately authorize the pipeline project, without approval from the PUC, and would allow Enbridge to start construction as soon as July.

“The Line 3 replacement project is urgently needed to replace a pipeline that was built in the 1960s,” Garofalo told ThinkProgress via email. “Failing to take action on replacing it will result in unneeded environmental risks.”

Opponents to the pipeline say Garofalo’s rider violates the state constitution and that it is an inappropriate use of the budgetary process. The state constitution holds that it is illegal to make laws “granting to any private corporation, association, or individual any special or exclusive privilege.” Garofalo’s rider specifically names the PUC docket number he wants approved.

For his part, Garofalo maintains that “there are several examples of legislation passed by both Democrats and Republicans that have addressed problems in this way.” He pointed to a bill Gov. Mark Dayton (D) signed into law last year, allowing a natural gas plant to be built without a PUC certificate of need.

Garofalo’s rider, along with others in the bill — namely one that would make regulators elected, rather than appointed, officials — appear to be an attempt to wrest control of pipeline approvals from experts and put it in the hands of politicians.

“It basically gives carte blanche to the company.”

“What they are specifically circumventing is the PUC’s review of the route,” Klemz said. “It basically gives carte blanche to the company. When you give that in combination with the power of eminent domain… That’s a real concern for us.”

Under Minnesota law, pipeline projects that have been certified can use eminent domain proceedings to force landowners to let the pipeline through.

Skirting the review process has burned regulators before: A key reason Line 3 approval has stretched on for two years is that its application came on the heels of a lawsuit over another Enbridge pipeline, known as Sandpiper. Minnesota regulators approved the Sandpiper project — which has subsequently been cancelled — without conducting a full environmental review. The court found that the PUC must do the review before issuing a certificate of need, which determines whether “the proposed facility is in the best interest of the state’s citizens.”

A misplaced investment

Enbridge estimates it will spend $2.6 billion on the U.S. side of the project, creating “thousands of family-sustaining construction jobs” and a “local and regional economic boost during construction.” There will be a short-term economic bump along the route, along with an influx of (mostly) out-of-state construction workers who specialize in pipelines. The project will certainly keep those workers employed throughout the construction process, and it will benefit local hotels and restaurants, but it isn’t a long-lasting economic boon.

The extension will also allow Enbridge to transport twice as much tar sands oil as before, with the new Line 3 bringing 760,000 barrels per day through Minnesota’s northern lakes region on its way to an Enbridge-owned oil terminal near Lake Superior. From there, the oil will be transferred to pipelines heading toward Houston, Texas, according to the company’s website.

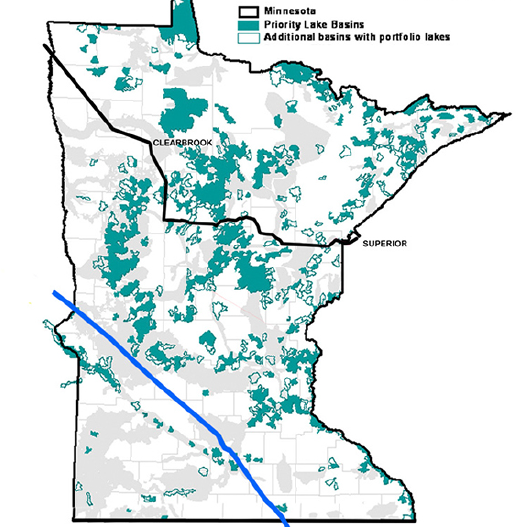

But the proposed path puts natural resources at risk, opponents say. The new Line 3 pipeline route cuts through Native American treaty land and crosses waterways where some of the only wild rice harvesting in the world takes place.

In April, hundreds of protesters rallied outside the Capitol building in Saint Paul. Honor the Earth, an indigenous environmental group, helped organize the rally of Water Protectors, as were seen during the Dakota Access Pipeline opposition at Standing Rock. The group calls Garofalo’s rider and the two others that would limit the PUC’s oversight “outrageous” and is pushing Minnesota’s legislature, governor, and the general public to reject the measures. Honor the Earth has also filed as an intervenor in the PUC proceedings for Line 3.

“Imagine that one day you wake up and find out that a pipeline company wants to run a thirty inch pipe with 375,000 barrels of oil per day through your burial grounds, sacred sites, medicinal plant harvesting areas, and, a mile from your biggest wild rice harvesting areas,” Winona LaDuke, executive director of Honor the Earth wrote in an essay.

“Standing Rock has sparked a historic resurgence of Indigenous Nations, and that we, as water protectors, are bringing that energy to the Great Lakes to fortify our resistance and stop the proposed Line 3 pipeline in its tracks,” LaDuke said at a rally in Northern Minnesota earlier this year.

The group has repeatedly complained about poorly run community hearings and a lack of opportunities to give feedback on the proposal.

“If this pipeline is needed, it should not go through Minnesota’s most valuable water resources,” agreed Richard Smith, executive director of Friends of the Headwaters, the Minnesota environmental group that spearheaded the lawsuit against the Sandpiper project.

He disagreed with Garofalo’s assertion that the current Line 3 is a greater risk than a new pipeline. “If the current Line 3 is dangerous, they would shut it down,” Smith said. “It’s not really a replacement pipeline because it’s not in the same place,” he added. Smith didn’t take a position on whether the line is needed overall. He just doesn’t want it going through the headwaters.

It’s the environment, stupid.

Tar sands oil, known in the industry as bitumen, is a sensitive topic for environmentalists, particularly people like Smith who worry about waterways.

When it leaks into water, as it did in Enbridge’s Kalamazoo River pipeline rupture in 2015, tar sands oil doesn’t float. It coats the bottom of the waterway and is both expensive and nearly impossible to clean up. Because tar sands oil is so thick, it has to be diluted — becoming diluted bitumen — to go in a pipeline. This, too, causes problems.

As a National Academy of Sciences report on this heavy oil dryly notes, diluted bitumen is “substantially” different from other oils. It’s denser, stickier, and more viscous. Meanwhile, the diluent also makes it volatile and flammable.

The NAS report found that the spills are harder to clean up and more damaging to the environment than other oil spills, which themselves are no easy task. “Diluted bitumen spills in the environment pose particular challenges when they reach water bodies,” the report says.

In addition, tar sands oil is one of the most carbon-intensive sources of energy in use today. For starters, it takes an incredible amount of energy just to pull bitumen out of the ground — like trying to mine for cold molasses. And, in the case of the Alberta tar sands, once the bitumen is out of the ground, it is still a very long way from where it can be refined and used. Bitumen is hard to transport. And the refining process is more intensive than it is for lighter forms of oil. All told, a gallon of gas made from tar sands petroleum is about 15 percent more carbon-intensive than one made with conventional oil, according to the Union of Concerned Scientists.

“When you are looking at the need for a pipeline, we do believe that you need to be looking at what are the upstream impacts of tar sands,” the Sierra Club’s Cathy Collentine said. She noted that a State Department environmental analysis for the Alberta Clipper pipeline — another Enbridge-owned line that will cross from Canada to the United State before connecting with Line 3 — included a section on the climate impacts of tar sands.

“It was interesting to see those included. For us, that leads to the conclusion that these pipeline expansions should not happen,” Collentine said.

That is not, however, the conclusion the State Department made back in 2009.

“While there is a consensus in the scientific community that global GHG [greenhouse gas] emissions have influenced climate change, there is no indication that the relative contribution of the proposed Alberta Clipper Project and the other large-scale and small-scale projects considered in the cumulative impact analysis would significantly contribute to climate change,” the final analysis says.

It’s a hypothetical question, but if massive tar sands pipelines — the infrastructure that brings carbon-intensive fuel to market to be burned — doesn’t contribute to climate change, what does?

Canada, like the United States and nearly every other country in the world, is a party to the 2015 Paris climate agreement, which seeks to hold global warming to less than 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. In order to achieve that goal, experts agree that tar sands oil cannot continue to be mined, refined, and burned.

No one wants to admit culpability in the climate crisis. And, speaking broadly, they aren’t exactly wrong. If you look at each project individually, it’s not a single driller or a pipeline, an SUV, or a power plant that is “causing” climate change. It is not one thing — it’s all of it.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimated eight years ago that 80 percent of the emissions through 2020 had already been guaranteed by energy infrastructure already in place.

“These pipelines have a shelf life,” Collentine said of Alberta Clipper and Line 3. “They have an ability to lock us into using fossil fuels — to using tar sands — for decades.”

Noting the overall decline in oil demand, Collentine asked, “What is it that is driving these increased capacity proposals forward? It’s certainly not need in Minnesota. It’s certainly not demand from consumers.”

Minnesota might not need this oil, but Enbridge does

Earlier this month, the CEO of Enbridge Energy rang the opening bell at the New York Stock Exchange. The occasion marked Enbridge’s merger with Spectra, a Houston-based natural gas company.

“We’ve grown significantly from what was once a primarily crude oil and liquids pipeline business into the largest diversified energy infrastructure company in North America,” Enbridge’s Al Monaco said.

But despite Monaco’s optimistic words, it’s unclear what the financial outlook for tar sands will be. Over the past year, many of the global oil and gas players —including ConocoPhillips, Shell, and Exxon— have divested from Canada’s tar sands. These companies are not pulling out because they have suddenly seen the light regarding the impact of their business on climate change; they make bets with money, and the money doesn’t look good in northern Alberta.

“It seemed like a good investment to companies like Shell and Exxon when they thought everything else was running out,” said Lorne Stockman, a senior research analyst with Oil Change International. “It was either this or drill in thousands and thousands and thousands of feet of water in the Gulf of Mexico or off the coast of Brazil.”

But then the fracking-driven Bakken boom came, OPEC adjusted production, and demand growth slowed down. There are several reasons the oil market isn’t as hot as it was five years ago. How, and to what extent, it will bounce back might be debatable, but even industry insiders aren’t too optimistic. The U.S. Energy Information Administration predicts “flat to down” consumption of oil in the United States. And last year, Shell Chief Financial Officer Simon Henry said that peak oil demand worldwide could come as soon as 2021.

Under a best-case scenario for Enbridge, Line 3 will just barely be operational by then.

“There’s not only a question of how much growth there will be, there’s a question of whether there will be any growth.”

“There’s not only a question of how much growth there will be, there’s a question of whether there will be any growth,” Stockman said. “They are all sitting, waiting for the mythical day that the oil prices rises enough to trigger multi-billion dollar investments in new growth. That day is consistently being pushed back.”

If things go as the industry plans, Canadian tar sands will be the source for oil passing through TransCanada’s beleaguered, unpopular, and now-permitted Keystone XL pipeline. They will be the source for another contested pipeline through northern Canada’s indigenous lands to the Pacific Coast, to be shipped to California refineries. And they will make their way, via the Alberta Clipper pipeline, to Minnesota’s Line 3.

“It’s more expensive, it’s more intensive, this is just the wrong move to be making,” Stockman said. “So many of those things are coming home to roost now. The sector is on its knees.”

The challenge of tar sands might be why both Transcanada and Enbridge have begun investing in natural gas reservoirs in Texas and Appalachia.

Meanwhile, Republicans — from President Trump’s support of Keystone XL to Rep. Garofalo’s heavy-handed efforts to get Line 3 approved — continue to support tar sands projects.

“It’s political. The Republicans have defined themselves in opposition to anything the Democrats did or [President] Obama did. If Obama was against pipelines, we’re for them,” Stockman said. “It’s like the coal thing. They are talking about reviving and industry that doesn’t really have a future anymore. They are behind the curve and they are using it for political purposes.”

All this development belies the economic realities of oil, according to Stockman. “With any luck, the fact that the emperor wears no clothes will reveal itself.”

—

Correction: An earlier version of this piece mistakenly said that the new Line 3 will carry 760 barrels of oil a day. The correct number is 760,000 barrels.