I met Peter Sokolowski, Merriam-Webster editor at large, on a big day for the dictionary. The day of covfefe. At 12:06 a.m., President Trump tweeted: “Despite the negative press covfefe.” Did anyone know the meaning of this word which, as far as anyone could tell, was not actually a word at all? Even the dictionary was stumped:

Wakes up.

Checks Twitter.

.

.

.

Uh…

.

.

.

📈 Lookups fo…

.

.

.

Regrets checking Twitter.

Goes back to bed.— Merriam-Webster (@MerriamWebster) May 31, 2017

It was a sassy and particularly timely response from a tome most adults associate less with the fast-paced political news cycle and more with a heated game of Scrabble. It also met Trump on his turf of choice — Twitter — and demonstrated a deft understanding of how to communicate, with humor and authority, on that platform. And it was exactly what readers were looking for. In a cultural moment in which once-trusted authority figures, both in government and in the media, are regarded with suspicion aplenty, people are turning more than ever to the most reliable of sources: The dictionary.

With its witty and pointed social media presence, Merriam-Webster has stepped in to helpfully guide its more than half a million Twitter followers through the lingual landmine in which we currently find ourselves.

When Kellyanne Conway spouted her Orwellian term of art, “alternative fact,” for example, Merriam-Webster was there with the definition of an actual fact. When United Airlines insisted that the man who was forcibly dragged off an overbooked flight was a “volunteer,” Merriam-Webster tweeted the definition of that term. (As one might expect, a volunteer is “someone who does something without being forced to do it.”) When Ivanka Trump offered an invented meaning for “complicit” — and when searches for that word spiked after a Saturday Night Live sketch called her exactly that — Merriam-Webster was there, dutifully noting the public’s interest and reporting on the word’s official definition.

📈A fact is a piece of information presented as having objective reality. https://t.co/gCKRZZm23c

— Merriam-Webster (@MerriamWebster) January 22, 2017

I caught up with Sokolowski at the Scripps National Spelling Bee in National Harbor, Maryland, where he was on hand to live-tweet the proceedings and represent Merriam-Webster, sponsor of the Bee for 60 years. Read on for his take on the dictionary’s buzzworthy Twitter feed, whether language is ever not political, and why he doesn’t think Merriam-Webster is “trolling” Trump.

Who runs the Twitter feed and how does it work?

We have a team. There was a woman who is mostly responsible for what people think of as the memorable, funny tweets, and she has a new job now. So it rotates… It’s a group of us, at this point. But the pattern has been established.

Was there a conscious decision made about what the tone of the Twitter would be? Did the election affect that?

Yes, absolutely. Honestly, they’re coincidences. About a year and a half ago, our editor of digital publishing, Lisa Schneider, she basically said — she’d been working for the company for a while, and she said, I’ve met so many of the editors and the people who write the dictionary definitions, and I find them to be really lively and funny. And yet, the social media presence was pretty tame. Boring, frankly. It could be wallpaper after a time, if it’s just the word of the day. So she basically said: I want to make an effort to make the personality that I see behind the scenes to the fore.

“The question of Ivanka Trump was, ‘Are you complicit?’ And she immediately responded, ‘If complicit means x…’ Well, that is an invitation to the dictionary.”

So she hired a wonderful writer, someone with a lot of knowledge about literature — so not someone from the world of social media, but someone from the world of word nerds, someone who loves reading and has a good sense of appropriateness of language, and good wit and wisdom, too. They found Lauren Naturale, and that became a full-time job. Her mission was clear: Let’s make this personality come through.

A year and a half ago. Let me think about what was going on then…

It was January 2016. The decision must have been made in the fall, and Lauren started in January. And then the idea was to, on the one hand, really promote the articles that we write about words. And of course, the trend-watching, which is what we’ve been doing on the website since May 2010. So in some ways, what Lisa decided to do was bring to the fore what we were already doing. The first trend-watch word was “austerity,” in May 2010, and it was about the Greek debt crisis. So we’ve been reporting this kind of information for a long time; it’s just that it suddenly became much more newsworthy.

As you say, you’ve been doing this a long while. But it does feel, as a reader, that there’s been a tonal shift, not just toward being more playful but definitely toward — and I think we’ve seen this across the board with institutions people probably think of as neutral and apolitical — choosing to have a much more clear point of view.

It maybe has sharpened our point of view, although we could also argue that the dictionary has always called balls and strikes on spellings and meanings. When, in public discourse, the question of meaning is raised, about a word like “fact” or “feminism” or “complicit” or “military,” then we can report on that communal curiosity, because our data tells us so. So not only does it tell us when people are curious about, say, misspellings or words in the headlines. When words that are used by public figures are actually not exactly in accordance with the way that word is generally understood, people go to the dictionary.

In some sense, those occasions, for those words like fact, feminism, complicit and military, they were invitations to the dictionary. The question of Ivanka Trump was, “Are you complicit?” And she immediately responded, “If complicit means x…” Well, that is an invitation to the dictionary.

When the public discourse raises the question of meaning, that means the dictionary is becoming an arbiter of discussion. We could begin having a philosophical conversation, breaking down the argument to the smallest constituent part, which is the word. Whether you’re talking about “fake news” or “alternative facts,” ultimately, what does this word mean? We don’t take that as being a political statement. But if it is political, then the only thing we mean by it is that we stand for reasonableness of discourse and a consensus of meaning of every given word. And that’s what we’ve always done.

It’s interesting to think about something as theoretically apolitical as: A word means what it means. A fact is a fact. But faced with so many public figures who treat facts as kind of launching pads for other ideas, do you feel like you — for lack of a better word — got drafted into being political?

Yeah, there was a hunger for clarity, I think. And answers. And also, that sort of objective, neutral resource. That maybe if you can’t trust media, can’t trust cable, who can you trust? I think that’s terrific. As a dictionary editor, I hope people trust the dictionary, and they turn to dictionaries in that kind of moment. As they always have, but now we have the data to prove it.

“When we’re reporting that curiosity, it is itself a speech act — we are reporting on this word that was used in a political context — so of course, you can’t deny, in a philosophical sense, we’re participating in a conversation about politics.”

Have there been any of these lookups, or any of the resulting definitions, that took you by surprise?

They all do. The one thing that’s really true is, it’s very hard to predict what words take off. For example, “volunteer” for the United Airlines incident. That’s an interesting case where, it went more viral than almost anything that was political in the last 15 months because, I think, there’s a cognitive dissonance in the messaging. The entire public basically said, wait, you’re using volunteer, we saw the video, the man was manifestly not volunteering. When there is some kind of a gap between the apparent meaning and the words that are used, that sends people to the dictionary.

When a common word is used in an uncommon circumstance, or when a very rare word is used in what would otherwise be a normal utterance, those are the words that people focus on. For example, the word “admonish,” that’s not that remarkable a word. It was one of the most looked-up words in 2009 when Congressman Joe Wilson stood up during one of the joint sessions of Congress [and shouted “You lie!” at Obama], but the official punishment from Congress was admonishment. So admonish is a word that may be unremarkable for a lot of adults but it suddenly became technical, governmental, punitive, or legal. And when a word becomes technical in that way, people look it up. What are they looking for? They’re looking for nuance and subtlety of meaning. And that’s what dictionaries are for.

“People don’t look up words because they don’t know what a word means… They’re looking for nuance and subtlety of meaning. And that’s what dictionaries are for.”

People don’t look up words because they don’t know what a word means. Most adults look up words they’ve encountered before. You’re checking the spelling, the meaning, some people are checking the origins. You’re looking, can this word be used this way? The word “emaciated” was the most looked-up word after Michael Jackson died, a word that maybe adults were familiar with, say, in the context of starvation, but not in the context of one of the most famous pop stars in the world. So we had this sort of break between the logic of the story and the word that was used. That gap is often filled by the dictionary definition. That’s the correct way to use the dictionary… And people underestimate how important a good definition is.

Why do you think they underestimate it?

They think it’s sort of a permanent, carved-in-stone monument to some historical time or period. Whereas I think of the dictionary, rather than being a permanent thing, I think of it as permanently improvable. Because language is changing, we have to revise constantly. That’s the job. We identify new words, of course. That gets some attention. But revising definitions to make sure we keep up with the language, that’s the job. That’s how languages and cultures evolve.

One thing I have noticed as a consumer of news is that because there is so much of it, and because people are called upon to speak publicly so often, it feels as if it is impossibly, frankly, for people to not stumble and misuse words, even for our most eloquent, thoughtful officials. And it does seem like we have an administration of people who are exceptionally reckless with language. Or just completely indifferent to its power and its meaning. I’m curious what you’ve picked up on in this landscape.

I think generally speaking, and this goes back to long before this administration. Any public figure who has a microphone in front of them, very, very frequently, it’s just — it’s not fair to judge them by every utterance. People made a lot of “refudiate,” for example, and there was evidence of that particular mistake going back to the nineteenth century. It’s a common error of language, like “irregardless,” which is so common that it’s actually in the dictionary. But we put a note there that says: You don’t want to use this word, you won’t be taken seriously. That’s our job as dictionary editors, to warn you about usage problems.

The problem is, if the clarity of meaning and the clarity of discourse are both kind of muddled, then it’s hard to know what’s being said. Which is, like this tweet last night. Nobody knows what it is! Presumably, it’s a typo. And typos aren’t that interesting… I’m glad that people turned to the dictionary because they wanted to see, is that a word? Of course, we have no record of it. There’s nothing we can say.

Have there been any moments when you, over the past election cycle and since this new president has taken office, when you’ve heard a word come out of someone’s mouth and you just knew: This is going to blow up our website. Everyone is going to be searching for “bigly.”

Some of them we see in real time. During the debates, I’m live-tweeting, so I’m looking at the data as it’s going. “Hombre” was one that was obvious. And partly we could see “ombre” and “umber,” we saw all three words spiking… “Bigly,” because he used it adverbily, and we only define it adjectively — and of course, he didn’t use it at all. He was saying “big league.” But even big league, we only define as an adjective and not an adverb.

The other one was Hillary Clinton’s use of “deplorable.” Deplorable was, again, she used it as a noun and we only define it as an adjective. So in both cases — big league and deplorable — there was this syntactic element, there was a grammatical problem. And all speakers of English, whether you identify it or not, know there’s something wrong or funny about that… In the case of both of those things, the word itself is newsworthy.

This is more of an existential question for you: Is language ever really apolitical?

No. And it’s a political act to tweet and report on them, because it’s a speech act. I like to say that the editor of Merriam-Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary, the one that’s being used for this Spelling Bee, used to say, “Tell the truth about words.” And what he meant was, do the research to find the evidence, the citations, in order to write the definitions. He was talking about a one-way street: Write the definitions so that they’re clear and based on evidence of real use. But today, we also know through our data what words people are looking up. This communal curiosity. And so we are completing that circle: We can tell the truth about words both in our reportage of their meanings and our reportage of the curiosity of the public.

So therefore, when we’re reporting that curiosity, it is itself a speech act — we are reporting on this word that was used in a political context — so of course, you can’t deny, in a philosophical sense, we’re participating in a conversation about politics. What’s more important to me is that the dictionary is part of the national conversation at all. I contend that we always were, but now we have the data to back it up.

Do you feel a sense, either on your part or on the part of readers, that the dictionary skews liberal or skews conservative?

That’s a very good question. We have solid evidence that conservative people love the dictionary, because we can see which words they look up. Or that they frequently watched Bill O’Reilly, because he used unusual words that would spike in our data and we could see, at 9:00 p.m., boom, there’s that word again. A word like “Pecksniffian” or “snollygoster” were words that he favored, that were oddball words, and he deliberately didn’t define them. So we have good evidence to show that people who watched that show would then turn to the dictionary. In that sense, it’s gratifying.

My theory, that I’m just coming up with now while talking to you, is that language is liberal but grammar is conservative. And I say that as a lover of both.

Well, here’s the thing. Of course you’re right. Because if you do something innovative in terms of grammar — and if you expand that definition to include spelling, for example — you will be criticized for it. So there’s an implicit conservatism. That’s what copy editors do. They maintain standards of practices that have been established over many, many years. And they shift slowly.

We just had the Kennedy centennial, and there’s a little article on the website that discusses the fact that when Kennedy was president, he was very criticized for his language. The most-criticized word that he used was the word “finalize.” And finalize was entered into our unabridged dictionary in 1961, which corresponds with his administration. And we were criticized in the New York Times twice in the same week, in the same article as the president! Because the conservative copy editors at the New York Times thought, this is not a word that should be either in this dictionary or in our president’s vocabulary. And yet, today, that is a completely unremarkable word.

“When we shame people on Twitter for misspelling something, we’re basically saying: You don’t know this thing that we, the agreed-upon group, also know. And that’s a class judgment.”

You see, in two generations — and the linguist Mark Lieberman at Language Log, he talks about 50 years as kind of a golden figure for the adoption of novelty. And finalize was clearly regarded as novelty in 1961. I don’t know a copy editor in America who would even blink at it today. So that is a relatively fast period of time for that kind of change to take place.

Is that kind of speed speeded up because of the internet and communication? Quite possibly. There’s a lot of words that we’re seeing now that perhaps we never saw before, a word like “meme,” or “impact’ as a verb. Certainly words like “access” as a verb, which I was corrected on in 1994. I wrote an academic article and it was not allowed in the article. In the margins, it said “jargon.” And no one goes through a day now without the verb access. So frequency makes it sound common to our ears, and comfortable.

Is any of it about democratization of who gets to decide what constitutes a real word?

Yes, very much. Absolutely. There’s a tension here. What is spelling, really? Spelling is arbitrary. And the Spelling Bee is a celebration of spelling, and of the dictionary. But ultimately it celebrates arcane knowledge. It’s extremely arcane to spell these words at this high level. So it’s, like any other athletic endeavor, these spellers are unusually good at something that’s unusually difficult. But you can go through life pretty well without spelling most of these words! So this is a celebration of the very specific difficulties of the English language, because it’s not phonetic and because we have roots from all these different languages.

In that sense, spelling, in some ways, is a shibboleth. When we shame people on Twitter for misspelling something, we’re basically saying: You don’t know this thing that we, the agreed-upon group, whatever that is, also know. And that’s a class judgment, based on education or region or race or age, just like any other judgment. We’re all judged, always, by the way we speak and spell.

Spelling, in that way, seems a lot like etiquette. It’s something you do mostly so that people know you know.

Yes, it’s manners. That’s why I say shibboleth. That’s exactly what that is. It’s a cue to the listener, to the reader, that you are both in the same club.

As somebody who has had access now to what people search and what words people are curious about, what is it you think you understand about the public that maybe most people don’t know?

The argument I constantly make, there really is something — I’m so glad you asked that question! There really is something. Which is: Curiosity is not ignorance. Very frequently, for example, at the beginning of a presidential debate, the word “debate” will spike and the word “moderator” will spike. And I will report this, and I’ll have very, very smart people — the people who follow me [on Twitter] tend to be word people — saying, “No wonder America is falling apart! People don’t know what debate means.” And I think: Absolutely not.

In this instance, when we’re all gathered as a nation in this very formalized way, what does debate mean? Does it have to be between two people? Does it have to be two people on opposing sides? Can a moderator be a shared responsibility? Is a moderator required to be a journalist? Does a moderator have to be neutral? There are all kinds of what I might call encyclopedic questions about the facts of this event that can be answered in the dictionary, just as you can answer the facts about what is a Cobb salad in the dictionary. If you look up a Cobb salad in the dictionary, you get the recipe. And they’re looking for the recipe of this event. You could be looking for something deeper, like etymology and where these things come from… I look at that as a celebration of what the dictionary is for, which is, to give that nuance, give that subtlety, in moments when you are asking yourself that question.

“There was a national conversation and the dictionary was right in the center of it. And that has happened more frequently in the last 15 months than at any time, possibly, in the history of our company.”

Because ultimately, when you are looking up a word in the dictionary, it’s a private act. You have your own reason, and I have my own reason. But when we all do it together for the same word, it becomes a communal act that we can report on, I think that’s profound. I don’t think it’s profound that we’re reported as trolling the president or correcting his grammar or something. That’s not what we’re doing. What we’re doing is reporting on a communal curiosity. That’s, to me, more interesting.

I think people use the word “trolling” too much.

I think it’s softened in meaning, I agree.

And I also think, because the president has made it so clear that he has disdain for facts and I think disdain for what he kind of bundles together as elitist concepts, and he probably includes the dictionary in that, there’s almost nothing you could do that would be in keeping with your guidelines that wouldn’t be perceived as trolling.

What’s gratifying to me is that we aren’t doing anything now any differently than we did seven years ago when we started Trend Watch. You’ll see a perfect consistency in the way we report them. The only difference is we do them more frequently now. But that’s natural. The other thing is that, when we reported on the word “volunteer” after the United Airlines incident, I looked at the news from the following day, and all the headlines said, “Merriam-Webster is trolling United Airlines,” and I just thought, well, what’s interesting about this is, there aren’t two sides of that story! There was no one defending the use of “volunteer” In that statement. So trolling has drifted in meaning away from a specific criticism to a generalized criticism in some way.

It’s a word people use, I think, to delegitimize any criticism they don’t like. Because I used to think trolling was deliberately egging someone on, whether you agree with the opinion you’re stating or not.

And it’s malicious. I think it was very clear when they were reporting on our reporting of the word “volunteer,” journalists seemed to be kind of jubilant about it. This is a vocabulary lesson for the country. And that, I do agree with. But trolling is their word, not ours.

📈'Volunteer' means “someone who does something without being forced to do it.” https://t.co/qNAcMyplhZ

— Merriam-Webster (@MerriamWebster) April 11, 2017

What was going on, really, is there was a national conversation and the dictionary was right in the center of it. And that has happened more frequently in the last 15 months than at any time, possibly, in the history of our company. That is new, that is different, and we were ready for it because we had this strategy in place, with a wonderful new staffer, long before any of this exploded… People have noticed, and that’s gratifying. We just passed half a million followers today. We got 30,000 more followers in the last 14 hours, because of that typo.

It’s funny because, when I went to bed last night, I saw some people tweeting at Merriam-Webster saying, “You’re my only hope” kind of thing. I thought, we will definitely have to comment on this tomorrow morning. But it turned out one of my colleagues saw it at that time and made a wonderful tweet. It was just the right tone, maybe inspired by a bit of the success we’ve had, but also, it was honest. It was saying, we see this in the data, and we have nothing to say.

I have to believe you get this question a lot: If everybody can just Google how to spell things, what is the value of knowing how to spell? Especially at the level at which these kids in the Spelling Bee can spell?

It becomes active knowledge. For most adults, spelling is passive knowledge. We get to a point where we’re competent, and that’s it. For these spellers, spelling is active knowledge. That means they are aware, usually of the etymology of a word because that gives them the best clues about how a word is spelled, and that connects them to the meaning of the word. So you can’t divorce the meaning from its origin from its spelling. That’s being a very active participant in your own language. And what could be better? Because that will never leave them… That really is something we can all take away from this, because you can be active in your knowledge of anything.

And here we are in the middle of a news cycle that is about spelling from the president, and it’s about spelling at the bee.

Which is so surreal.

That was our word of the year last year, as you might recall. And the definition of surreal is terrific. A lot of definitions are not helpful. It’ll be “of or relating to surrealism.” However, the definition for surreal is: Marked by the intense irrational reality of a dream. That’s a terrific definition. The word “dream” is important because we’re talking, ultimately, about the artistic movement of surrealism that was the post-Freudian expression of a dream life. The melting clocks of Dali. So dream is there not only for the image of the reader but specifically, it refers to the psychiatric use of that word. Intense is perfect, and irrational is perfect, and reality. The intense irrational reality of a dream. It seems very real, but it’s not.

And what is “sur,” it means above, or over. So above the real, over the real, more than real. You break a basic word like that down, that becomes this active knowledge that you carry with you and you recognize that words have power and words matter. And that’s what these kids know.

This might be too partisan a question, but as someone who loves and values words as you do, is it hard to go from a president who, by all accounts, was an incredibly eloquent person who deeply understood words and their significance to someone who is, it seems, very reckless with words and doesn’t really care about them that much?

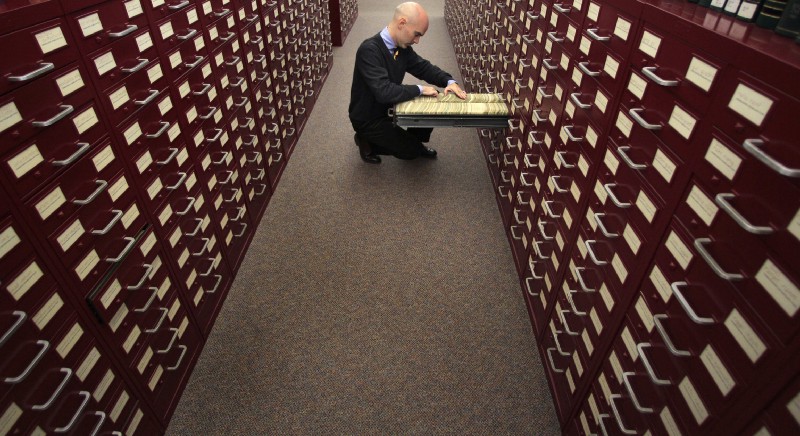

I really can’t comment on that! I don’t think there’s anything I can say that’s helpful. We pay attention, but what we’re paying attention to is much broader than one person. We want the weight of evidence to help us with what we call citations, and our office has these drawers with 17 million cards — it’s the largest body of collected evidence of any language in the world, as far as I know — that’s just the paper. So we want accumulated evidence. Individual use is idiosyncratic, and as soon as I comment on individual use, it becomes a criticism.

People commented on Obama’s language, too. Words that were used by President Obama that were looked up tended to be words that were used in a very specific, narrow, legal sense, a constitutional sense, that also had a generic meaning. So he was driving people to the dictionary, too, just in a different way. He had a kind of technocratic vocabulary, so he would use those terms.

The biggest one, though, for him, was “sartorial.” When he wore a tan suit. He, himself, did not use that word. But that was the word used by the press. That was maybe the biggest spike associated with Obama, although it was a word he didn’t use.