Banks that pulled funding from the Dakota Access Pipeline due to strong public opposition are now teaming up with the pipeline’s developer on another controversial fossil fuel project. Energy Transfer Partners, the lead developer of the Bayou Bridge Pipeline in south-central Louisiana, is using the lessons it learned from the Dakota Access Pipeline saga to win both financial and political support.

Bayou Bridge LLC, the company building the pipeline, is a partnership between Energy Transfer Partners and Phillips 66, whose primary business is petroleum refining. Two banks that pulled funding from Energy Transfer Partners’ Dakota Access Project due to public opposition — DNB Capital and US Bank — are both financing Bayou Bridge through credit agreements with Phillips 66 and Energy Transfer, according to a new report released Thursday by the Public Accountability Initiative (PAI), a nonprofit public interest research group.

“US Bank and DNB Capital publicly stopped financing Dakota Access when activists called attention to the pipeline’s impacts on indigenous communities,” Robert Galbraith, a senior researcher at PAI and author of the report, said in a press statement Thursday. “But both are still lending to the companies building Bayou Bridge.”

Despite Energy Transfer Partners’ dismal safety and environmental track record, financial institutions are lining up to loan the company money. Altogether, 40 banks have granted access to a total of $12.25 billion in credit to the companies building Bayou Bridge, according to PAI.

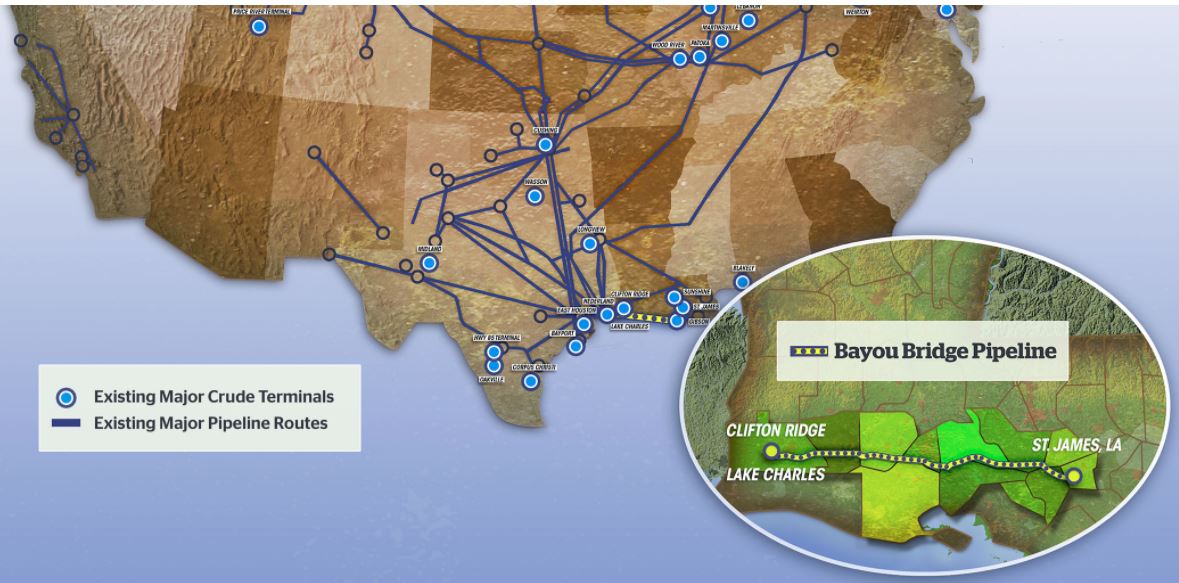

The pipeline is proposed to carry 280,000 barrels of crude oil per day through 11 Louisiana parishes, crossing 700 bodies of water and more than 700 acres of fragile wetlands. If constructed, Bayou Bridge would impact watersheds that supply drinking water for up to 300,000 people.

Even though it’s proposed in a region long accustomed to the impact of the oil and gas industry, the Bayou Bridge project is facing stiff resistance. Residents are growing less tolerant of the cumulative impact of living in a region filled with fossil fuel infrastructure.

Bayou Bridge, however, enjoys broad political support from both major parties in Louisiana — evidence of the outsized power enjoyed by the oil and gas industry in Louisiana, thanks to its political donations and funding of university professors.

Former Sen. Mary Landrieu (D-LA), for example, testified in support of the pipeline as a paid consultant of Energy Transfer Partners at the same time as she was registered to lobby for the Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, a state authority that still must rule on whether to grant a permit for the pipeline. This relationship “presents a major conflict of interest for the regulatory body which must approve of the Bayou Bridge pipeline before it can be built,” Galbraith said.

Academic institutions in Louisiana are also taking in large sums of money from fossil fuel advocates, according to the report. Louisiana State University (LSU) published a paper commissioned by Energy Transfer Partners touting the benefits of Bayou Bridge. These collaborations between industry and academia have become increasingly common across the country.

The LSU report was influential in securing necessary approvals and building public support for the pipeline, according to Galbraith. It was cited in numerous media reports and was submitted as testimony to Louisiana state Department of Natural Resources, which approved a permit for the pipeline.

The LSU report was prepared by David Dismukes, executive director of the university’s Center for Energy Studies. In addition to heading the Center for Energy Studies, Dismukes also runs a private economic consulting business, Acadia Consulting, that does work for the oil and gas industry, “though this work is often difficult to distinguish from his work at the public university,” Galbraith said.

In response to complaints by local residents, the industry says building fossil fuel projects like Bayou Bridge in concentrated areas is better than having pipelines and petrochemical facilities strewn across Louisiana.

With the odds stacked against them, though, opponents to Bayou Bridge were able to achieve a rare victory last summer when the Louisiana board that regulates the private security industry denied a license for TigerSwan, a North Carolina-based security contractor that was hired by Energy Transfer Partners to oversee security during the Dakota Access Pipeline protests.