Last year was very likely the hottest year on record, according to the authors of a new study in the journal Science.

The study examined “multiple lines of evidence from four independent groups” measuring ocean heat and concluded “ocean warming is accelerating.” Researchers found the rate of warming for the upper 2,000 meters of ocean has increased by more than 50 percent since 1991.

As a result, “2018 is shaping up to be the hottest for the oceans as a whole, and therefore for the Earth,” a press release accompanying the study explains.

“Global warming is here, and has major consequences already,” it adds, bluntly. “There is no doubt, none!”

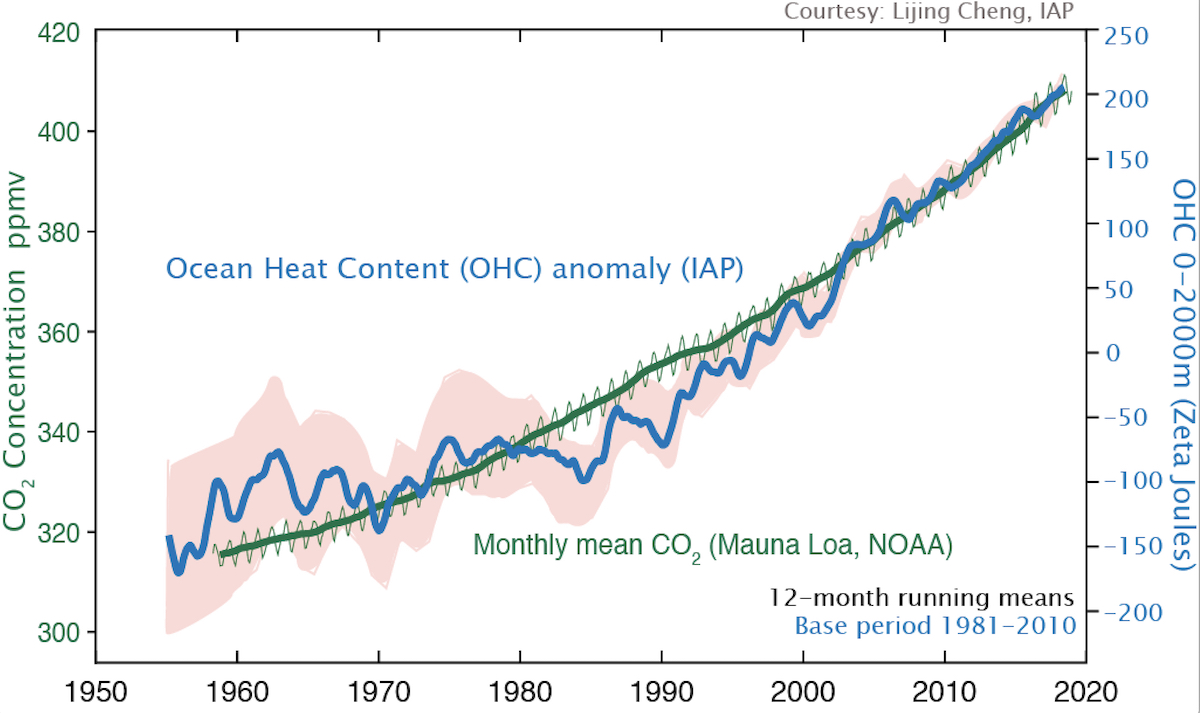

The speed up of ocean warming can be seen in the chart below, provided to ThinkProgress by the study’s lead author, Dr. Lijing Cheng of the Institute of Atmospheric Physics (IAP), Chinese Academy of Sciences.

The measurement of ocean heat content (OHC) has gotten much more accurate in recent years, something the authors were able to take advantage of.

“For over a decade, more than 3,000 floats have provided near-global data coverage for the upper 2,000 meters of the ocean,” the study explains. This new Argo system of floating measurement devices provides “superior observational coverage and reduced uncertainties compared to earlier times.”

These high-quality Argo observations combined with other independent, older ways of measuring OHC, have enabled the authors to provide “the context of the record-breaking recent observations to be properly established.”

Often, most people think of global warming as solely about surface air temperatures. But, as the authors point out, there are two reasons ocean heat content are a much better measure of actual global warming than surface air temperatures, which have traditionally been used to determine what years are the hottest on record.

First, as the study states, the oceans take up “about 93 percent of the Earth’s energy imbalance created by increasing heat-trapping gases in the atmosphere from human activities.” So the overwhelming majority of warming ends up in the oceans.

Second, “ocean heat content is not bothered much by weather fluctuations that do, however, affect the surface temperatures.” And OHC is only “somewhat affected by El Niño events,” which can have a big, short-term impact on surface temperatures.

All of this makes ocean heat content a truer and more stable measure of how fast the Earth is warming under climate change.

Thus, when the data show that 2018 has set the record for ocean heat content, that tells us 2018 sets the record for hottest year.

As co-author Kevin Trenberth, a distinguished senior scientist in the Climate Analysis Section at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, told ThinkProgress, “global warming is close to ocean warming and 2018 will be the warmest year on record, followed by 2017.”

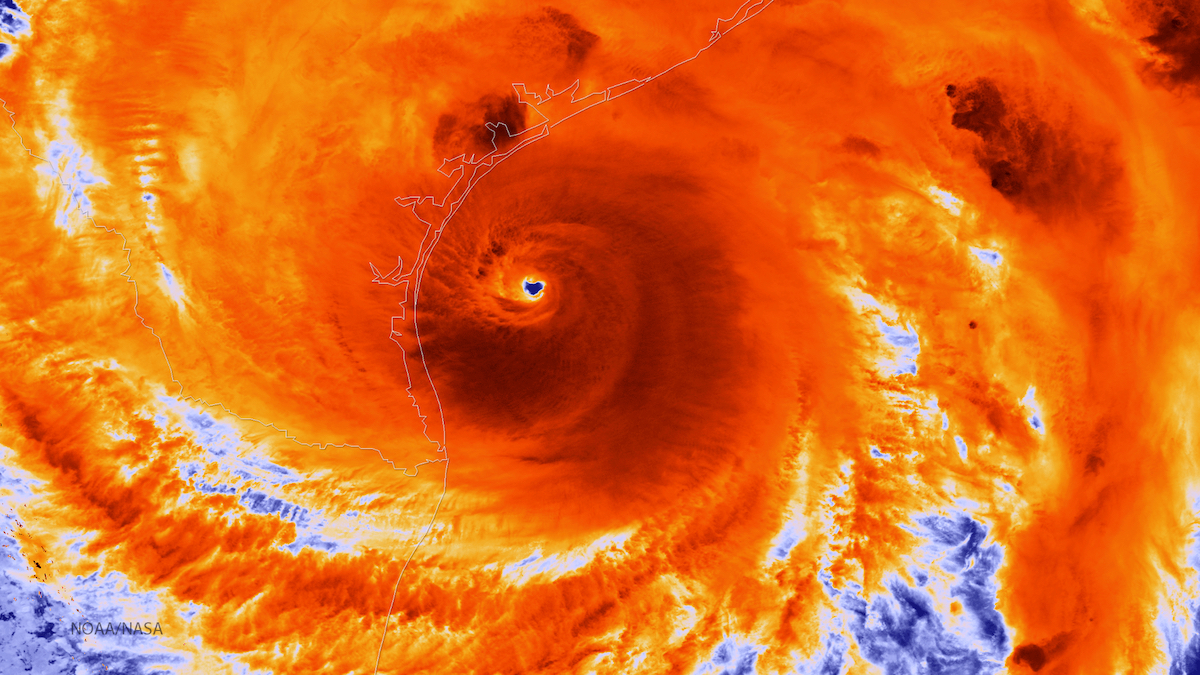

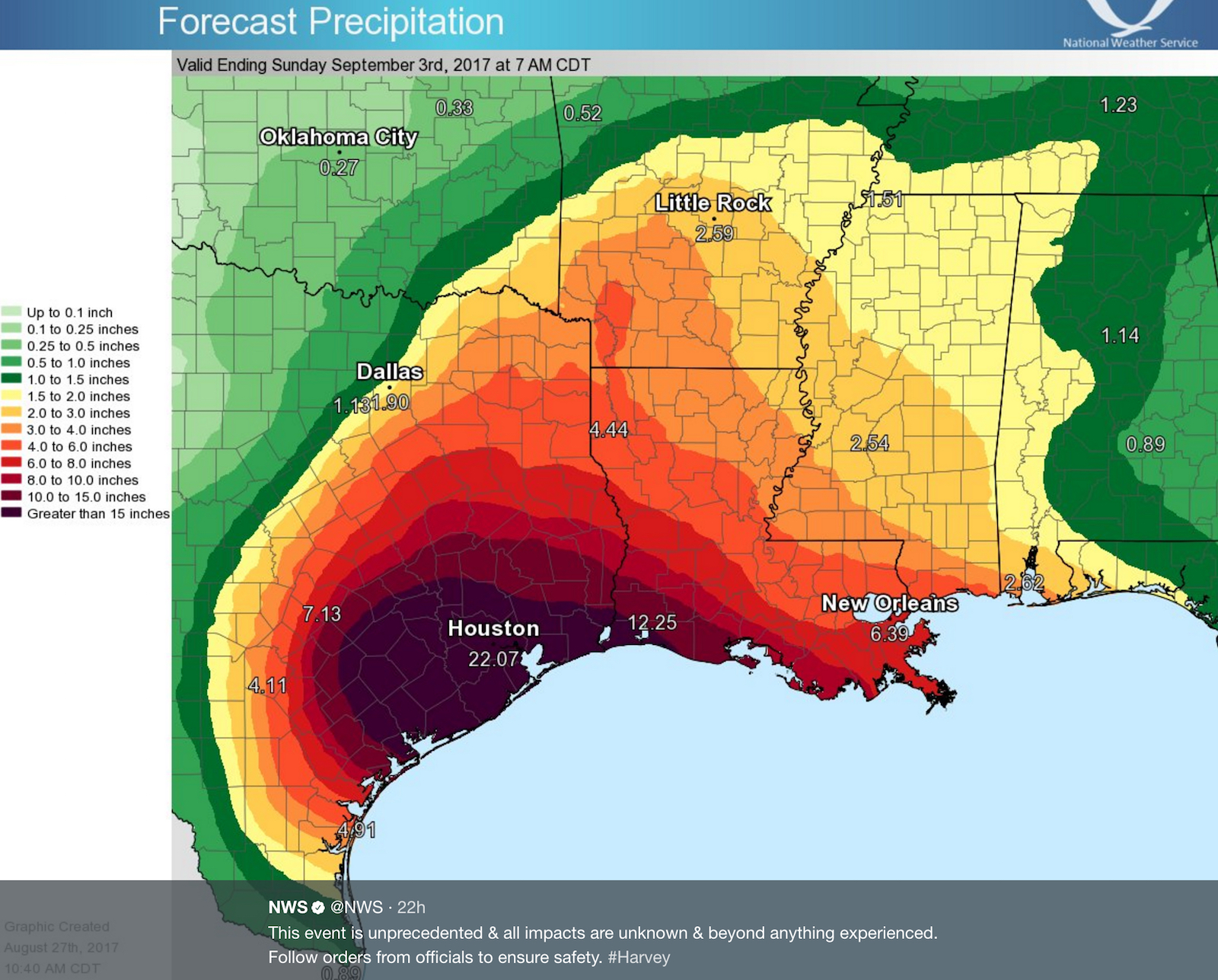

Trenberth, a leading expert on the connection between climate change and extreme weather, pointed out that “one of the warmest spots was where Hurricane Florence developed this past year [in the Atlantic] and where Hurricane Harvey developed the previous year [in the Gulf]. The warm water fuels the evaporation and moisture for storms.”

It is “too late to stop ocean warming in this century because ocean response” is so slow, warned Cheng. Water stores a lot a heat, so its temperature fluctuates much more gradually. But, she said, we can slow the rate of warming if we “act as soon as possible to reduce carbon emission.”

As Cheng’s chart shows, ocean heat content is very strongly linked to global CO2 levels. Unfortunately, CO2 levels (or concentrations) won’t stop rising until the world reduces annual global CO2 emissions to near zero, which is in fact the ultimate goal of the December 2015 Paris climate accord.

But we are a long way from releasing zero emissions.

“While there still is time to do something to slow this process down, it is too late to stop serious global warming,” study co-author John Abraham, a professor of thermal sciences at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota, told ThinkProgress,

Abraham warned that global warming “is happening faster than we previously thought.”

“We are also seeing the impacts, from superstorm hurricanes and typhoons, to drought and deadly wildfires,” he continued. “We are paying the consequences for ignoring the science for decades. What a terrible legacy the denialists have left us and our children.”