On a day like any other, Abraham Medina was walking home from school in Garden Grove when he faced a decisive moment: One wrong move could have landed him in juvenile detention, but the quick-thinking teenager knew what to do.

A police officer had stopped Medina, pointed at some nearby graffiti, and asked the high school student whether he had spray-painted the graffiti. Medina responded that he wasn’t responsible. He said that the officer then gestured toward a paint spray can abandoned near the sidewalk curb and told Medina: “Why don’t you pick that up for me.”

Medina declined and walked away. More than a decade later, and now an adult, Medina reflects on that day and sees clearly how the situation could have easily escalated and possibly led to his arrest for an offense he had not committed.

“I get so angry, knowing that if I would have been naïve at that moment, to think of what would happened,” said Medina, 28.

That experience was not an isolated one. Medina said he and his friends were constantly stopped by police officers in Garden Grove, where he grew up, and in Santa Ana, where he spent much of his free time. On his Santiago High School campus, Medina said police officers would pull students aside and question them during and after lunch to determine if the students were in gangs and to collect information for police files.

Medina went on to study at the University of California, Irvine, but he never forgot how he, his classmates, and neighborhood friends were treated during the tough-on-crime era that swept up generations of youth into the county juvenile justice system.

Medina knew that this aggressive approach to the policing and prosecution of Latino youth simply locked the so-called troublemakers away behind bars, but didn’t get to the root of what was driving youth to act out or commit crimes.

So five years ago, Medina began working and speaking out on behalf of the city’s youth as part of Santa Ana Boys and Men of Color (BMOC), an organization focused on keeping youth in school and out of the juvenile justice system. Whether it was making presentations before the Santa Ana school board, collaborating with Orange County probation officials on alternatives to detention, or simply connecting with youth and parents at community forums, Medina made one thing clear: detention and punitive measures were not helping Santa Ana’s youth.

Instead, Medina advocated for the adoption of restorative justice practices, which eschew traditional forms of punishment such as juvenile hall detention and school expulsion, in favor of practices that allow youth to take responsibility for their actions, but also provide intervention services to get to the root of their behavioral issues.

But he and his colleagues at BMOC, where until last year he served as project director, noticed a common thread among the young boys they served. Many had mental health and behavioral issues coupled with learning disabilities, said Medina, who is earning his master’s degree in legal and forensic psychology.

“Our programs are designed to be culturally informed and trauma informed, but definitely we are challenged by youth who have dual diagnoses,” said Medina. “And these youth are the ones who end up in the juvenile justice system, and the juvenile justice system sometimes doesn’t know how to respond to them.”

“These youth are the ones who end up in the juvenile justice system, and the juvenile justice system sometimes doesn’t know how to respond to them.”

During sessions for Joven Noble — an in-school BMOC program that teaches at-risk youth responsibility, respect, and decision-making skills — Medina and his colleagues noticed that some of the young boys couldn’t pay attention or were hyperactive. Other students that Boys and Men of Color worked with in Santa Ana’s alternative education schools would act impulsively, walking out of class on their teachers when they felt disconnected.

In an effort to determine why students were behaving this way, Medina said BMOC worked to examine all factors that could be impacting crime rates and juvenile delinquency, including trauma and chronic environmental stress.

It was only a few years ago that Medina learned at a community forum on gang injunctions about research showing an association between crime patterns and leaded gasoline emissions. Nonetheless, he was shocked to learn that Santa Ana soils contain levels of lead that are hazardous for children and questioned whether the city and county had done enough to determine how widespread lead soil contamination is in Santa Ana.

“I do feel that these are lives that are at stake. [Lead] can mean the difference between having a successful life, or one that leads to the justice system or incarceration or even a mental health institution. And it’s very alarming,” said Medina, who is now executive director of Resilience Orange County, an organization he helped create via the merging of BMOC with another group in late 2016. The organization nurtures young leaders to engage and address systemic problems such as the over-incarceration of youth of color in the criminal justice system.

A ThinkProgress investigation found hazardous levels of lead in almost a quarter of more than 1,000 soil samples tested in homes and public spaces throughout Santa Ana, a city that is predominantly Latino and where more than 30 percent of the population was under the age of 18 in the last census. ThinkProgress also found that the number of Santa Ana children tested with dangerous levels of lead in their blood exceeds the state average by 64 percent.

ThinkProgress presented Medina with its soil test results, as well as California Department of Public Health blood lead level data for Santa Ana children. That data also show that thousands of children annually have blood lead levels that are not high enough to prompt public health intervention because they are below the federal actionable level of 5 micrograms per deciliter, but do fall into the category that researchers says could result in a lower IQ and other behavioral issues.

Many of the youth that Medina works with live in the same neighborhoods and zip codes where ThinkProgress found high levels of lead — areas that police also described as current or previous hot spots for juvenile crime, as well as gang and drug activity.

Medina’s concern is that approaches championed by police and prosecutors in these neighborhoods, such as the use of gang injunctions, don’t consider factors such as lead contamination. Gang injunctions are civil orders that limit illegal and otherwise legal, everyday activities of a gang’s members in “safety zones.” Associating in public, for example, is restricted in these zones.

“If we are able to see that in places of the city where there are high levels of lead in the soil that they also happen to be hot spots of crime, or we happen to see that the youth from those zip codes end up in juvenile hall, this would have a serious impact on the juvenile justice system and on the school district, on the city, in the community, and on parents,” said Medina. “I feel this information could change the way we do things.”

Linking lead-contaminated soil and incarceration in California

Over the last decade, juvenile justice systems across the nation, including the Orange County Probation Department, have implemented reforms to reduce the number of minors in juvenile detention.

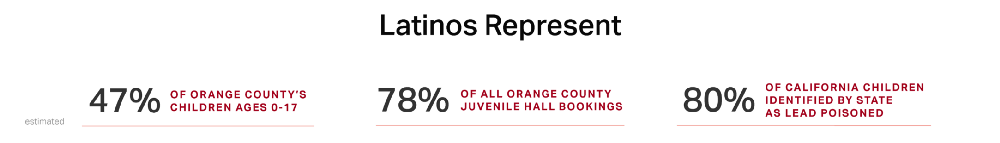

But even with these reforms, youth of color continue to be disproportionately detained. In Orange County, probation department data from 2015 shows that Latinos comprised 78 percent of all juvenile hall bookings.

Latino children represent about 47 percent of Orange County’s child population, according to a 2014 American Community Survey estimate. Latino children also comprise a majority of childhood lead poisoning cases in California, according to state public health data.

Anaheim and Santa Ana also consistently rank among the top five zip codes with minors booked into Orange County juvenile hall, per a seven-year analysis on data from 2009 through 2015 conducted by the Orange County Probation Department for ThinkProgress.

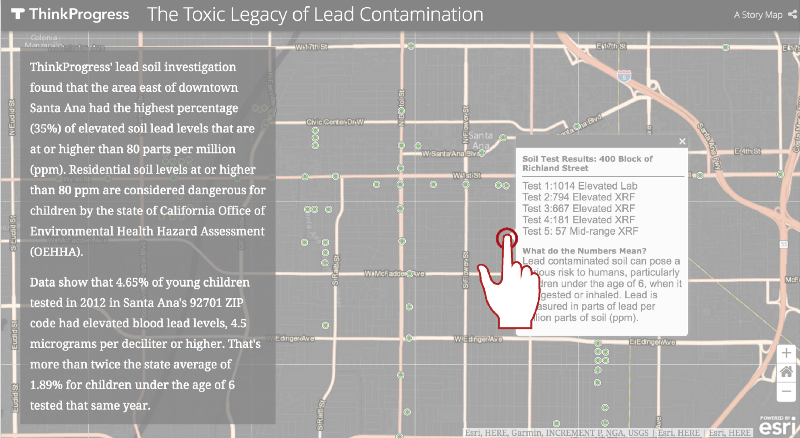

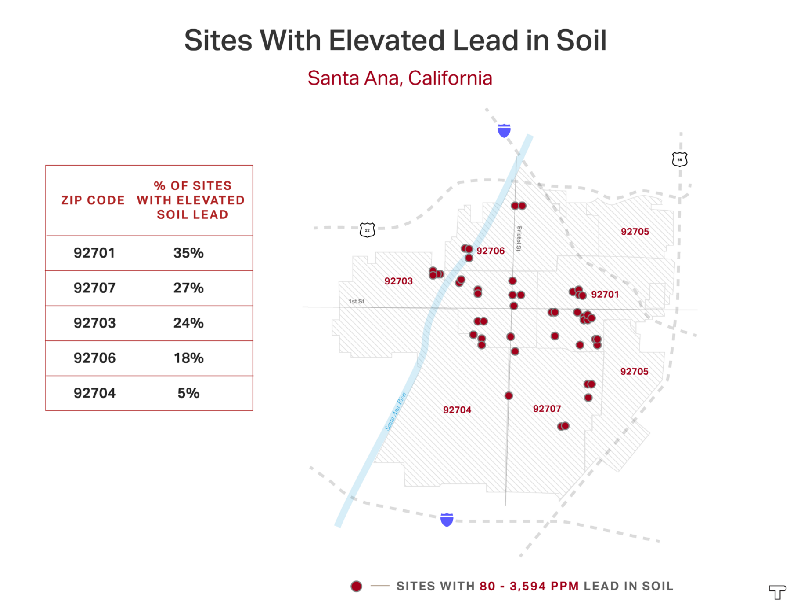

Among the top Santa Ana zip codes, 92701, just east of downtown Santa Ana, also had the highest percentage (35 percent) of elevated soil lead tests that ThinkProgress conducted throughout the city. These soil levels were at or higher than 80 parts per million, the level considered dangerous for children by the state of California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA).

Among all zip codes in Orange County, this one also had the highest percentage of children under the age of 6 with blood lead levels at or above the actionable level set by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (5 micrograms per deciliter), according to 2012 data provided by the California Department of Public Health. This same zip code also has the most children in Orange County with elevated blood lead levels at or above 9.5 micrograms per deciliter, according to state data from 2009 to 2011.

The lead soil tests conducted by ThinkProgress also showed that the 92707 zip code in southeast Santa Ana had the second-highest percentage of elevated soil lead levels with 27 percent, followed by 92703 in northwest Santa Ana with 24 percent of its test results higher than 80 parts per million.

State childhood blood lead data shows that both areas likewise rank among the zip codes with the highest percentage and number of children with elevated blood lead levels in Orange County.

More specific juvenile hall booking data from Orange County Probation for the same seven-year period shows that, except for 92704, the Santa Ana zip codes with the highest juvenile booking rates are also the zip codes that have the highest percentage of elevated lead soil tests, and the greatest percentage of children with elevated blood lead levels.

The top offenses at booking for all Orange County youth are probation violations, followed by warrant arrests, burglary, robbery, and gang activity, according to the seven-year period analyzed.

Orange County Probation Department Division Director Daniel Hernandez, who oversees the juvenile division, couldn’t pinpoint why Anaheim and Santa Ana top the list of all Orange County cities with the most juvenile bookings.

“The only consistent things that we see between those cities is that they are the most populated cities, and most densely populated cities,” said Hernandez.

Former Santa Ana Police Chief Carlos Rojas, who began working in Santa Ana in 1990 as a patrol officer and stepped down as chief earlier this year, said that like other cities across the country Santa Ana has experienced a downward trend in crime in the last 30 years, with spikes during some years over that span.

Rojas credits multiple factors for the turnaround, including the redevelopment of dilapidated apartment complexes, outreach efforts by nonprofits that work with youth, and targeted policing.

But research suggests there may be another factor that has contributed to that decrease in crime across Santa Ana.

The impact of childhood lead exposure on crime rates

University of Cincinnati Professor Kim M. Dietrich’s long-term study examining the impact of lead on criminal behavior built on the research of Herbert Needleman, a pioneering pediatrician who documented the effects of low levels of lead exposure on children.

Needleman’s studies, starting in the 1970s, were the first to suggest that lead exposure might be associated with a higher risk for juvenile delinquency and adult criminality, said Dietrich, who is director of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine.

In 1979, Dietrich launched a study following a group of children who lived in Cincinnati neighborhoods with a high concentration of older, lead-contaminated housing. When Dietrich began his lead study, he was advised by colleagues and federal officials not to focus his research on lead because “lead is dead.”

The first documented outbreak of childhood lead poisoning happened more than a century ago in Brisbane, Australia, Dietrich pointed out, but children continue to be the barometer of environmental lead today because the public assumes that lead is no longer a problem until an outbreak such as Flint occurs.

“But [lead] always raises its ugly head over and over again, and when it does, it always has to do with kids,” said Dietrich.

Dietrich’s groundbreaking 2008 study followed 250 individuals from the original study and found that when the Cincinnati children reached adulthood there was a strong relationship between criminal behavior and their exposure to lead in the womb as well as their childhood exposure to lead.

“We continued to follow them into early adulthood and we found that [lead exposure] was also associated with adult criminality particularly those behaviors that are associated with violent acts,” said Dietrich, whose study controlled for other factors such as health, demographics, and parent’s criminal behaviors.

The researchers found that for every blood lead level increase of 5 micrograms per deciliter at six years of age, the risk of being arrested for a violent crime increased by almost 50 percent.

The researchers also found that about 55 percent of the individuals had at least one arrest: Among men that number was higher at almost 63 percent, and lower among women at 36 percent. After the age of 18, the male participants were arrested an average of five times, while the women were arrested an average of one time.

None of the children in the Cincinnati lead study had blood lead levels below 5 micrograms per deciliter, said Dietrich, noting that they were all very highly exposed by contemporary standards.

“Although both environmental lead levels and crime rates have dropped over the last 30 years in the US, the overall reduction was not uniform — inner-city children remain particularly vulnerable to lead exposure. The findings therefore suggest that a further reduction in childhood lead exposure might be an important and achievable way to reduce violent crime,” the study found.

“So when the first results came out I was actually quite shocked, to be honest,” said one of the study’s co-authors and University of Cincinnati Criminal Justice Professor John Paul Wright, who did not expect to find an association between lead and violent crime. Having previously worked with longitudinal data, he said, he knew it would be “very, very difficult” to measure an effect that’s generated in childhood, much less a biological effect in childhood.

“I did the analyses in multiple ways trying to eliminate as many rival hypotheses as possible to eliminate the effect. Once I was certain what was there was there, we turned it over to a biostatistician who reproduced those results,” said Wright.

Lead’s effect on violent crime remained, even controlling for other factors such as socioeconomic status, which Wright said is a factor that itself impacts lead exposure.

A newly-released study from the National Bureau of Economic Research also confirmed a significant relationship between lead exposure and juvenile delinquency. The researchers found that suspensions and juvenile detentions rise with preschool blood lead levels.

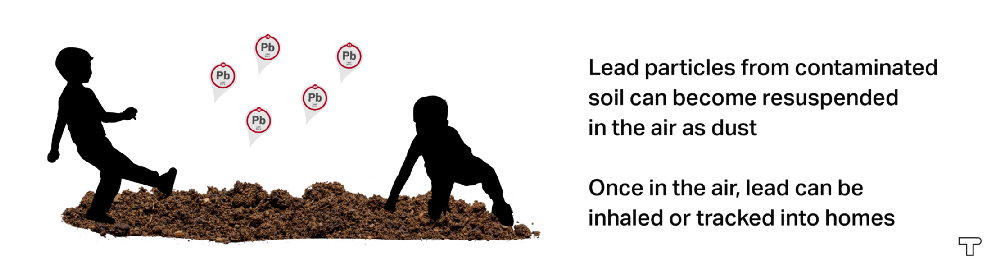

The bulk of the roughly 120,000 Rhode Island children who were part of the study were youth with consistently low blood lead levels and exposure, and included relatively few cases of children with acute lead poisoning. The researchers focused on lead-contaminated soil, a key source of chronic lead exposure among urban children.

Although the case has gotten stronger with this research as well as other studies, the impact of lead on criminal behavior has remained controversial.

“Even if it’s something like a neurotoxin like lead there’s a general disciplinary bias against recognizing those connections and pointing them out,” said Wright.

Dietrich described the problem as an extreme bias by the criminal justice research community against any biomedical explanation for criminal behavior.

“There’s no question that social capital factors play an important role, and no one is denying that. But what we are trying to say through our research is that lead exposure, at least in some cases, may be playing a role,” said Dietrich.

Leaded gasoline emissions and crime trends

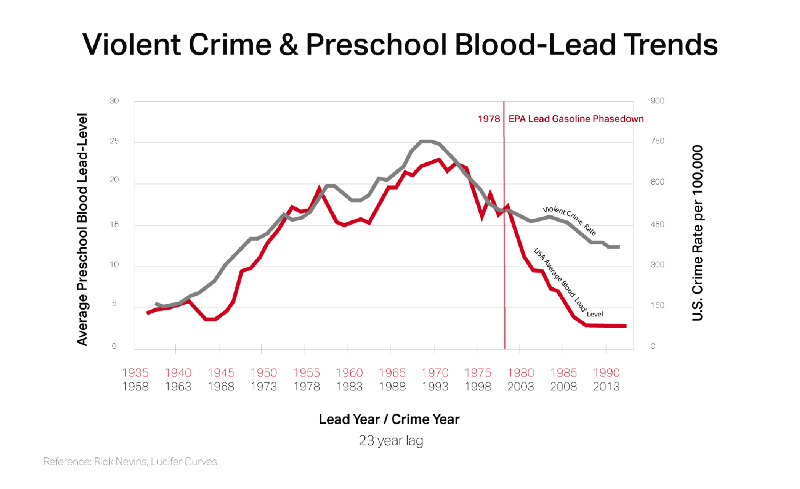

Economist Rick Nevin first found that U.S. trends in violent crime showed a “striking association” with blood lead levels and gasoline lead exposure for very young children. More specifically, gasoline vehicle emissions patterns in the United States mirrored violent crime patterns, with a time lag of 23 years, meaning that early childhood lead exposure affected the peak age of violent offending.

Nevin’s hypothesis, published in a 2000 peer-reviewed study and followed up with his 2007 study examining lead exposure and international crime trends, expanded upon the work of other researchers who found that lead-burdened children displayed more aggressive and delinquent behavior.

Gasoline-related lead exposure can be traced to the 1920s when manufacturers originally added tetraethyl lead to gasoline to keep engines running smoothly. With the mid-20th century boom in automobile use and expansion of federal highways across the country, U.S. consumption of tetraethyl lead gasoline nearly quadrupled from the 1940s to the 1970s, according to data from the U.S. Geological Survey.

Average blood lead levels tracked trends in air lead fallout from leaded gasoline during that same period, according to Nevin, with children in urban centers particularly impacted by both gasoline emissions and exposure to lead paint in aging homes. In the 1960s, crime rates began to increase.

The use of lead additives declined starting in the 1970s with the auto industry’s introduction of catalytic converters, which required unleaded fuel. In 1978, the EPA also adopted a National Ambient Air Quality Standard for lead that would require “a drastic reduction and eventual elimination of lead in gasoline and major reductions in emissions from lead smelters,” according to the book Lead Wars: The Politics of Science and the Fate of America’s Children by historians Gerald Markowitz and David Rosner.

The largest phase-down of leaded gasoline began on Jan. 1, 1986 after the EPA ordered a 90-percent reduction in the amount of lead allowed in gasoline. Lastly, via the Clean Air Act, the federal government banned leaded gasoline for on-road vehicles starting Jan. 1, 1996.

Crime rates peaked in the early 1990s and then began declining.

Nevin concluded that 90 percent of the violent crime rate variation from the early 1960s up until 1998 could be explained by the trends in lead exposure from the previous decades.

In his 2007 report, Nevin found “a very strong association” between the blood lead levels of preschool children and subsequent crime rate trends in eight other countries including Britain, Canada, France, and Australia.

Nevin’s hypothesis about the relationship between violent crime and lead exposure was confirmed in subsequent studies by researchers who studied the issue at the state level and city level.

For example, in a 2007 report, Amherst College economics Professor Jessica Wolpaw Reyes examined the lead-crime correlation at the state level across the United States.

Wolpaw Reyes estimated that the reduction in lead exposure in the 1970s is responsible for a 56-percent drop in violent crime between 1992 and 2002. She described the relationship between childhood lead exposure and violent crime rates later in life as both robust and significant.

“While the results herein imply that lead could be one of the most important factors influencing violent crime in the United States, this effect on crime may be just the tip of the iceberg,” wrote Wolpaw Reyes.

A 2015 Brennan Center for Justice study on “What Caused the Crime Decline,” didn’t draw a conclusion on the leaded gasoline emissions-crime hypothesis because the researchers weren’t able to secure state-by-state data from 1980 to 2013.

The researchers did acknowledge that based on current research, it was possible lead played some role in the 1990s drop in violent crime, though possibly not as large of a role as Wolpaw Reyes found, and that lead’s effect on crime likely waned in the 2000s.

But the Brennan Center study doesn’t mention the exposure risk that children continue to face from leaded gasoline emission particulates that settled in the nation’s soils and remain there still today.

Soil lead expert Howard Mielke, a professor at Tulane University’s School of Medicine in New Orleans who has been studying the effects of childhood soil lead exposure for decades, conducted an ecological analysis of air lead emission levels with violence levels in six U.S. cities.

Air lead explained between 66 to 90 percent of the variation in reported aggravated assaults from 1972 to 2007 across the cities, according to the 2012 study.

Mielke and co-author Sammy Zahran also found that while previous reductions in lead emissions significantly reduced blood lead levels, the risk of exposure persists because of accumulated lead dust in urban soils.

“By preventing child [lead] exposure now, society may realize numerous benefits two decades into the future, including less violence,” the study concluded.

Like Wright and Dietrich, Simon Fraser University Professor of health sciences Bruce Lanphear has found that most criminologists have ignored the findings of epidemiologists and economists showing lead as a factor in the drop in violent crime across the United States.

“By preventing child [lead] exposure now, society may realize numerous benefits two decades into the future, including less violence.”

Instead, criminologists have focused on other factors, which should be recognized, but placed in context, said Lanphear. He cited the finding in Wolpaw Reyes’ 2007 study that less than 30 percent of violent crime was due to all other factors such as the size of a police force, economic factors, and birth weight.

“So the criminologists really just haven’t kept up because they are fixated on and focused on other issues,” said Lanphear. “Lead seems to be a major, if not the major reason for this epidemic of crime in this past century.”

All of this accumulated data makes it clear that lead is associated with problem behaviors, said Lanphear, who also conducted a study that estimated that one in five cases of ADHD in U.S. children could be attributed to lead exposure.

Lack of public awareness about dangers of lead in soil

Among the Santa Ana parents with whom youth advocate Abraham Medina works, there is very little awareness about the dangers of lead in soil. At one 2015 community meeting where gasoline lead emissions and crime were discussed, Medina said parents shared their knowledge about lead in Mexican candies, for example, but knew nothing about leaded gasoline emissions.

Parents told him, for example, that they allow their children to eat dirt, believing that it strengthens a child’s immune system.

Medina attributed this to a lack of public information as well as a failure by government officials to provide a comprehensive communication campaign about lead dangers specific to Orange County.

Medina’s hope is that ThinkProgress’ findings will trigger a deeper investigation into soil lead levels to find potential sources, and that government institutions serving impacted youth, such as the Santa Ana police department, will re-think their approaches to addressing behavioral issues that might be triggered by lead exposure.

Medina said that ultimately the juvenile justice system is not the appropriate place to address these issues, particularly for lead-burdened youth.

“The challenge is: what is the system really going to do if the youth who have these behavioral problems are making mistakes that they might not necessarily effectively learn from because of their underlying conditions,” said Medina.

Gabriela Hernandez, a community activist and mental health therapist who works with children in several of the neighborhoods with elevated soil lead levels, said her hope is that youth caught in the juvenile justice system are treated with the knowledge that lead may be a possible contributor to their behavior.

Hernandez, who has advocated against the use of gang injunctions, said that often youth who are placed on probation or gang injunctions have developmental delays.

“That has not prevented [police and prosecutors] from over-criminalizing them, over-sentencing them, or charging them as adults,” said Hernandez.

Providing the community with data about lead hot spots is critical to detect potential issues with affected boys and girls and to provide the proper intervention, she said. Collaborations between the educational system, the mental health community and other agencies will be key to ensuring youth are properly diagnosed and helped, said Hernandez.

“Early detection is really, really important for everything: for the school system, for the criminal justice system, for probation,” said Hernandez.

Medina believes that once parents and the greater Santa Ana community learns about the dangers that contaminated soil continues to pose for youth, they will demand answers.

“If it’s about 10,000 [lead-burdened children] a year — that’s a significant population that the city of Santa Ana has to address and provide support for,” said Medina.

“But for the families,” he said, “These are children whose lives might be permanently impacted and the question is whose fault was this and could it have been prevented.”

This project was made possible through the generous support of a community health reporting fellowship from the International Center for Journalists.