Mothers, take heart: your children may mean you’re actually more productive at work even if you feel more stretched.

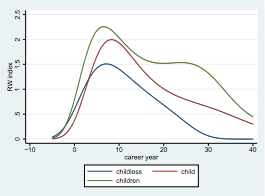

A new study of academic economists quantified this fact. At the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Matthias Krapf, Heinrich W. Ursprung, and Christian Zimmermann looked at the publishing output of people with and without children, quantifying productivity by how much the academics produced. They found that women with at least two children at home are more productive, on average across their careers, than those who have only one child, and mothers of one child are more productive than those with none. The same trend held true for fathers. “[C]ontrary to conventional wisdom, economists with children are not less productive than their childless colleagues,” the authors write. “This statement also applies to women.”

They note that this doesn’t mean that having children actually causes higher productivity — but it also dispels the opposite idea, that being a mother makes an employee less productive. In fact, they find, “pregnancy, childbearing, and motherhood have no large effect on the mother’s research productivity in the first three years after the birth of her first child.”

They do find, however, that there is a drop in productivity associated with each additional child at home under the age of 13. That drop in productivity means that a mother of two loses about two and a half years of research output by the time her children become teenagers, and the mother of three loses four years. But their productivity appears to pick up afterward, smoothing out the impact.

This evidence flies in the face of how mothers are perceived at work. Studies have found that mothers are seen as less competent and committed at work as well as not being good candidates for hiring, promoting, training, or paying higher salaries, while fathers aren’t penalized and are sometimes rewarded for having children. In academia, this means that married women with children are less likely than men and than childless women to get tenure-track professorships.

This plays out at least in part in wages, as a woman will see her wages decrease by about 4 percent for each child she has, while a man’s paycheck will go up by 6 percent. The wage gap between childless women and mothers has been growing and is now the same as it was in 1977 even as the gender wage gap overall shrinks. As one researcher put it, “Fatherhood is a valued characteristic of employers, signaling perhaps greater work commitment, stability, and deservingness.”

But that’s not the on-the-ground truth. Besides mothers being more productive, they are also better employees. Both employers and the women themselves report that having children makes them better a multitasking while women also say their time management and organization improved. And they’re putting in more and more work generally: The typical mother increased her work hours by 150 percent between 1979 and 2012. Women’s work overall has boosted GDP by 11 percent.

It’s no wonder that women end up having to get more organized after having children. While men have nearly tripled the time they spend caring for their children and doubled the time spent on housework, women still do more of both. Mothers today in fact spend more time on child care than the mothers of the 1960s. Imagine how much more mothers could do if we had universal childcare, paid family leave, paid sick days, and better access to flexible schedules to help them juggle children and work.