Over the past week, a story has gone viral nationally about a Virginia transgender student who was forbidden from sheltering in a locker room with her classmates during a lockdown drill. But, as the student’s mother explained in an exclusive interview with ThinkProgress, that incident follows years of discrimination she’s experienced at the school.

Amy, who asked only to be identified by her first name for her family’s privacy in their small town, told ThinkProgress that her daughter “Paige” (a pseudonym) has been prohibited from using any gendered facility at the school for nearly four years. That’s why, according to Amy, “there was a tremendous amount of confusion about where exactly my daughter should shelter” during the drill. Paige is literally forbidden from entering either the boys’ or girls’ locker rooms, so when the drill took place, her teachers honestly weren’t sure whether an exception could be made.

“This is exhausting work,” Amy explained. “I shouldn’t have to fight so hard for one child to just be able to go to school and be safe with her peers.” Yet despite the national attention and uproar that erupted after the incident, the school board at its meeting this week announced no immediate policy proposals to prevent it from happening again. The superintendent, who is new to the district, did apologize to the family, but nothing has otherwise changed. In the meantime, Paige is still not permitted to use the girls’ facilities.

“It’s the responsibility of not just our schools, but our school boards and all the people involved in our school system to make sure that every single child feels taken care of,” Amy said. “And my child has not felt taken care of by her school board.”

Years of discrimination

When Paige first came out as transgender at age 10 back in 2015, she was the first transgender student the Stafford County School District administration had ever been asked to accommodate. And at first, Amy recalls, they were actually very supportive, allowing Paige to use the girls’ bathroom at her elementary school. “They asked a lot of questions, they asked her a lot of questions about what she needed, and they did the best they could to accommodate that.”

That lasted all of two weeks — until a group of angry parents wearing “Save Our Schools” stickers confronted the school board about their accomodations. Amy described them as speaking “very disgustingly against my child” and “saying very, very awful things,” such as calling her a “predator.” The Stafford County School Board unanimously agreed to reverse the school’s decision to let Paige use the girls’ restroom.

Elsewhere in Virginia, the Gloucester County School Board had made the same decision to restrict Gavin Grimm’s bathroom access just three months prior. Grimm, a transgender boy, was mounting a legal fight against his school, making it a “hot topic” at the time. (Grimm’s case is actually still ongoing over a year after he graduated.) Amy feels that Paige, as the only out trans student in Stafford, was similarly made an example of.

Unlike in Gloucester, however, Stafford didn’t pass any written policy governing how the district would treat transgender students. They only made a decision about Paige specifically, leaving it to the individual schools across the district to make their own decisions about how to respond in other cases. “That obviously hasn’t worked very well for us,” Amy said, pointing out that Paige is now in her second school in the district and neither has accommodated her. She’s also heard from parents across the district whose trans kids are facing similar restrictions.

Since that 2015 school board decision, Amy has had to meet with school officials every summer to talk about how to protect Paige’s safety and ensure she receives the best education possible, but that has never resulted in allowing Paige to use the restrooms. It has resulted, however, in ongoing humiliation and ostracization for Paige.

In elementary school, classes would be taken to the bathroom as a group, with the students divided by gender on either side of the hallway. They’d then go into the restrooms two at a time. “It was humiliating for her,” Amy explained, “because she would have to walk down a completely separate hallway to go use the bathroom.”

Likewise, in her middle school, Paige is forced to use a bathroom located in a main hallway heavily trafficked by all students — and nowhere near her classroom. She is not permitted to use the gym’s locker rooms, which means she is denied access to a gym locker. She alone must carry her gym clothes with her in a bag and change in a separate restroom. When she stays after school to hang with her girlfriends, Paige can’t go to the bathroom with them. One time she tried, and a teacher actually pulled her out.

These are experiences that transgender students have reported across the country, and studies have shown such isolation can have a negative impact on their mental health, how safe they feel at school, and their academic performance. Some even avoid using the restrooms entirely, which can have serious repercussions for their physical health.

“It’s embarrassing,” Amy explained, “and something that makes me the most sad about that is that I don’t think it makes her that upset anymore. She’s used to it and doesn’t know anything different. She’s known two weeks of freedom.”

She’s known two weeks of freedom.

But despite her brave, resilient demeanor, recent events have shown that Paige is still very much affected by this daily discrimination.

The drill

On Friday, September 28, Paige was in PE, her fourth block class, when a lockdown drill began. While the students and staff retreated into the locker rooms, the teachers at first had Paige remain in the gym sitting in a chair with a teacher. After the teachers openly debated what should be done, they decided to move Paige to just inside the locker room door, but she was kept isolated in the entry hallway away from the rest of the students, who were in the locker room proper.

The humiliation of the whole experience caused Paige to have a panic attack. According to Amy, some of the teachers thought she was just upset because the drill was scary. “One teacher recognized what was really going on and why she was upset,” Amy said. After the drill, “she told [Paige] alone privately that she didn’t understand why they were doing it that way, that it wasn’t right, and that if she ever needed anything or support or someone to talk to, she was always there for her.”

Amy doesn’t entirely blame the other teachers, because she recognizes that the policy may have put them in a difficult situation. “They’ve been told she’s not allowed to go into the girls’ locker room,” she explained. “So when you’re told that by those above you, whether that’s administration or the school board, that this is the rule… they were probably afraid if they let her in there that their jobs were at risk.”

“Part of me would like to think we can just use some common sense and say, ‘This is a lockdown drill… This is a situation where we’re practicing for something that could happen and we need to make sure we do it right,” Amy said.

But as Paige explained in a note to the school board this week, she felt like “an afterthought.”

The school board meeting

News of Paige’s experience first started circulating because of a note posted on Facebook last week by Equality Stafford, a group that promotes LGBTQ inclusion in Stafford County schools. The note encouraged the community to show up to this week’s school board meeting and show their support, which they did.

Paige wanted to speak for herself at the meeting, but the board’s rules require that any public speaker share their name and address, and Amy wasn’t comfortable that it would be safe for her. In fact, Amy wasn’t even sure she was comfortable letting Paige attend the meeting, but Paige was insistent. As tough as the drill itself was, Paige seemed to “bounce back pretty quickly” and wasn’t bothered by the attention the story was receiving.

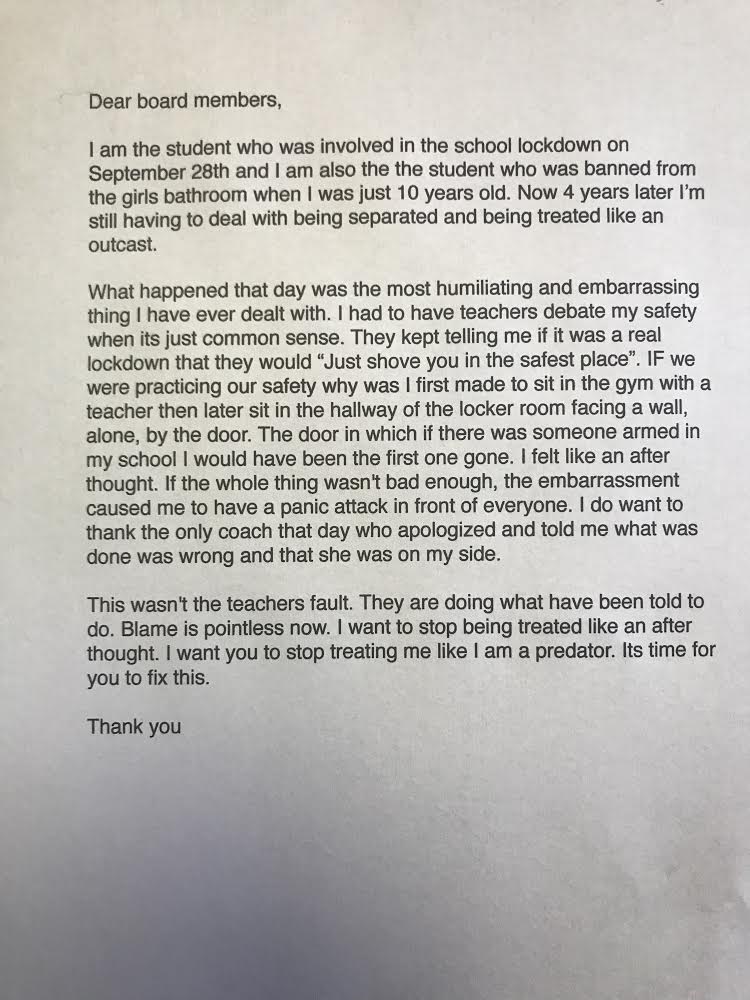

They agreed to let Paige craft a statement about her experience that didn’t include any identifying details, and at the meeting, Amy asked her aunt to read it to leave room for some anonymity. “When my aunt started reading, by the end of the first sentence… Paige started bawling. She let out a gasp and she just started bawling.” This cascaded to other people, as family friends and strangers alike began crying upon hearing Paige’s story. “I think she had been holding that in for a little while,” Amy said. “And I think hearing her words read out loud by a family member who also got choked up while she was reading it — I think it just hit her in that moment.”

In her statement, Paige described four years of suffering, “being treated like an outcast.” She recounted the events of the drill and how it made her feel to be treated differently from the other students in a crisis situation. “If we were practicing our safety, why was I first made to sit in the hallway of the locker room facing a wall, alone, by the door?” she wrote. “The door in which, if there was someone armed in my school, I would have been the first one gone. I felt like an afterthought.”

“Blame is pointless now,” she insisted. “I want to stop being treated like an afterthought. I want you to stop treating me like I am a predator. It’s time for you to fix this.”

“She was surprised she got so upset hearing it,” Amy added. She’s always admired her daughter’s resilience, but she also worries about the cumulative effect of all this rejection. “That’s a lot for any adult to deal with,” she said, noting that Paige’s story is by no means anonymous among her friends and community. “She cried and cried and cried, and then she was okay.”

Superintendent Scott Kizner, who’s only been serving the district for about a month, publicly apologized at Tuesday’s meeting. Amy acknowledged that he has apologized to her and to Paige privately as well, which they appreciate. “It’s the only apology we’ve ever gotten through all the years we’ve been in the school system… for the way she’s been treated.” She believes the apology was important to see for LGBTQ students and staff throughout the county who can’t be out and open and she hopes it sets a tone for moving forward.

“At the same time, words are cheap,” she countered. “I want to see change. It’s appreciated, but it doesn’t change anything. Until something changes, I’m going to keep working to make sure it does. The fact is: When my daughter went to school today, she still had to use a separate bathroom and she still had to change in a staff bathroom. The apology didn’t change anything for her because she still has to go to school the next day and deal with the fallout.”

The fact is: When my daughter went to school today, she still had to use a separate bathroom and she still had to change in a staff bathroom.

Amy is optimistic about change, but she doesn’t want to force that change through legal channels. She wants the school to recognize that it’s the right thing to do. Tuesday’s school board meeting, she said, “was the first time that I have felt optimistic they were willing to implement policy and trainings because it was necessary and meaningful.”

Along the way, there have also been “amazing” teachers who have treated Paige as if she were their own daughter. “If it wasn’t for those teachers, I don’t think I would have such a strong, resilient child that has amazing self-esteem, and gets straight A’s, and is popular and is thought of as a leader among her peers.”

Amy is left to imagine what it would be like if every teacher in the district felt like they could fully support their LGBTQ students without the limitations imposed by the board and administrators. “What a difference that would make,” she said. “Not just for the LGBTQ kids, but to that straight kid that doesn’t have a lot of friends or feels like an outcast, or for any kid who feels a little different — and they all do — to just see that support and that love from teachers. I don’t think that just helps LGBTQ kids, I think that helps all the kids.”