After years of troubling reports of serious human rights violations on the part of Cameroon’s security forces, the U.S. government has finally decided to cut military aid to the country.

By all accounts, the violations were egregious: Targeted killings, torture, kidnapping, burning schools and villages, and more.

And so it was with “shock” but also relief that rights activists such as Adotei Akwei, managing director at Amnesty International USA, received the news that the country’s security forces would no longer be receiving $17 million in military aid, which would have been spent on things like patrol boats, armored vehicles, training, airplanes, and drones.

But why now?

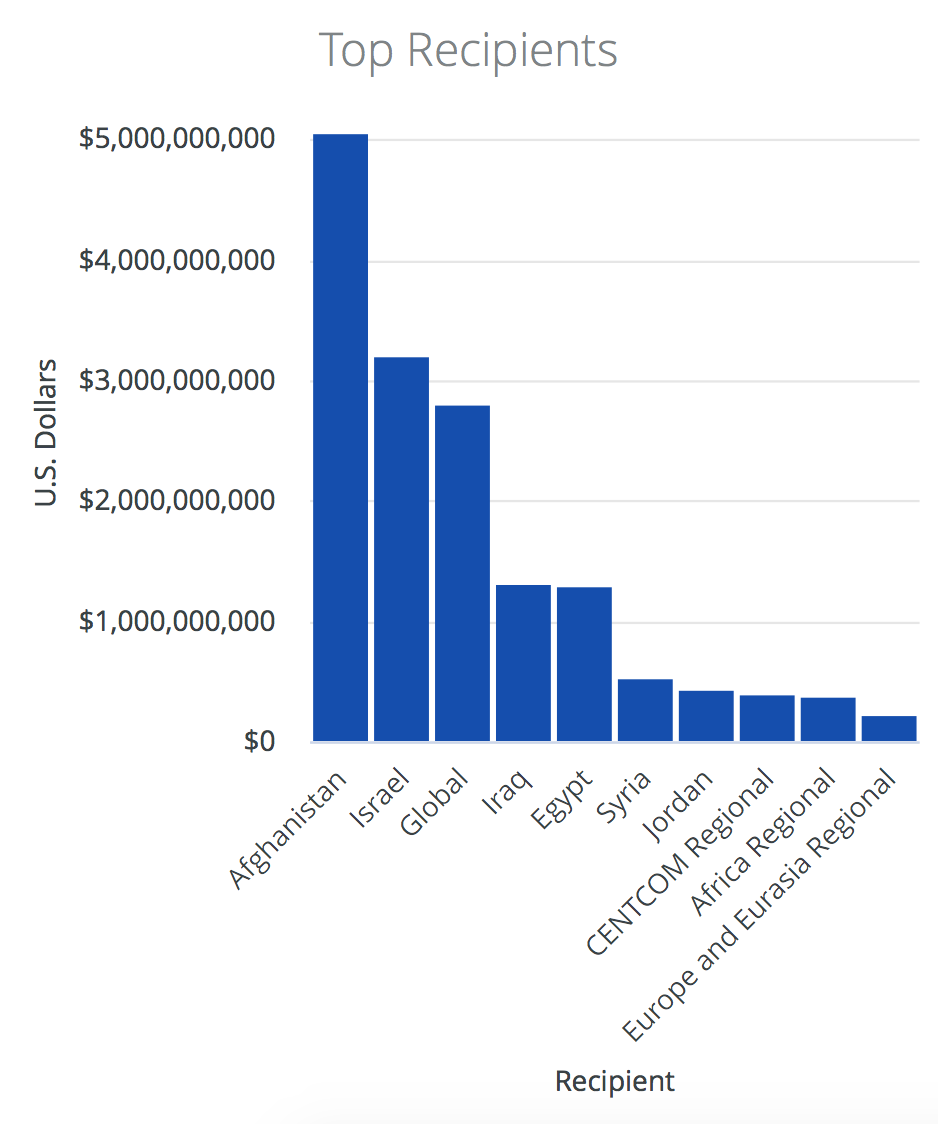

“I have no idea,” Akwei said, admitting that if he did, he would apply the same approach to other rights violators receiving U.S. military aid. And there are many: The United States provides military to 142 countries in 2018 (at $17.88 billion), and many of them, like Cameroon, violate human rights.

It’s important to note why the United States is even in Cameroon — and most of these other countries — to start with: The war on terrorism. The U.S. military aid is all in service of that purpose (with others receiving funds to fight drug trafficking). Many of these countries use their anti-terrorism laws to target dissidents, activists, journalists, and minorities.

“These human rights violations are increasingly — obviously — not Trump administration priorities.”

Akwei starts rattling off he lists of countries that also regularly open fire on civilians –Niger, Chad, and Nigeria top his list. The Nigerian military, for instance, which will get $12.9 million in U.S. military aid this fiscal year, killed at least 26 unarmed protesters last October, falsely claiming the protesters had been throwing rocks. The Nigerian government later justified it by noting that Trump himself said U.S. troops station at the border with Mexico could shoot rock-throwing migrants.

Human rights violations in Egypt are also well documented — the mass arrests of activists, journalists, and members of the LGBTQ community are not a secret. And yet, the country is among the top recipients of U.S. military aid.

Stephanie Savell, research associate at Brown University’s Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, told ThinkProgress that this is important to consider in the greater context of the United State’s global military footprint, which is huge.

In addition to the 142 countries that get military aid from the United States, Savell, whose research is included in the Cost of War project, has found that Americans actively engaged in counterterrorism operation in at least 80 countries.

Cameroon, she said, “is a drop in the bucket in some ways, in the larger scope of activities. So we cut back a little bit of aid in Cameroon, but it’s still happening in other places. And Cameroon is not the only not-so-democratic country that we’re working with,” she added.

And she notes that the United States is well aware of it. For instance, the State Department’s 2017 Country Reports on Terrorism plainly states that, “Ethiopia also continued to use the ATP [anti-terrorism proclamation] to suppress criticism by detaining and prosecuting journalists, opposition figures – including members of religious groups protesting government interference in religious affairs – and other activists.” And yet, between 2012 and 2019, Ethiopia received over $71 million in military aid.

So many guns, so little accountability

The Leahy Law prohibits the State Department and Defense Department from giving military assistance to foreign security forces that violate human rights, but having a regulation and applying it are two different things.

Amnesty International is currently pushing U.S. lawmakers to apply those restrictions to the Nigerian troops responsible for the October killings.

Military training and engagement have a place, said Akwei, especially in countries facing threats by armed extremist groups such as Boko Haram. But good faith, accountability, and transparency have to be part of this transaction.

Even with Cameroon, there have been commissions created, but there have been no reports produced that could be used to hold people accountable, he explained.

Christina Arabia, director of the Security Assistance Monitor at Center for International Policy, told ThinkProgress that this lack of oversight and accountability are not limited to the United States. Russia and China, for example, also provide a lot of military aid all over the world. And they don’t have an equivalent to the Leahy Law.

“We at least make an effort to say that there is a condition on human rights — I also say that cynically. But Russia and China don’t do that,” she said.

But the Leahy Law can be circumvented, said Arabia.

“One unit is caught attacking civilians, and they can say, ‘O.K., we’ll give aid to a different unit.’ But how do we know that those foreign military commanders aren’t shuffling people around? It’s hard for us to have oversight of that,” she said.

In fact, she said that in many of these countries, corruption helps extremist groups with their recruitment. Corruption — often brought on by grinding poverty — means “ghost soldiers” in Iraq, who get paid but never exist, and it means guns go into black markets and money ends up in the wrong hands.

Furthermore, she said that most of these counterterrorism programs fail because “there is no risk assessment done beforehand, nor is there follow up afterwards.”

There’s a number of reasons for this, but chief among them, is that, “Holding partners accountable is difficult,” said Arabia, adding that things that don’t directly affect the United States are unlikely to get a U.S. response.

“These human rights violations are increasingly — obviously — not Trump administration priorities,” she said. “You even see that in his new Arms Export Control Act, in which economic experts have been elevated over human rights.”

It’s going to get worse

Activists and watchdogs don’t differentiate much between U.S. military aid and weapons sales, largely because can go hand-in-hand. For instance, the United States give billions in military aid to Israel and Egypt each year, but the bulk of that is used to buy U.S. weapons.

And weapons sales — be it to countries who get aid, or countries like Saudi Arabia, which get other kinds of military cooperation for their operations (say, in Yemen) — are about to get a lot more fast and loose.

The United States, said Akwei, now has “an incumbent in the White House that clearly believes that more business for the military industrial complex benefits the United States, and this is also an administration that does not believe in multilateralism or diplomacy. So transactional weapons sales are the cuisine of choice at the moment.”

And once U.S. arms are out there, there’s a good chance they will end up on the black market. Consider another report by CNN earlier this week showing that American guns sold to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates are ending up in the streets of Yemen, sometimes in the hands of anti-government Houthi rebels. (This is a heck of a twist for the Trump administration, which has accused Iran of arming the Houthi rebels).

The Trump administration is finalizing its new arms export rules, which transfer the oversight of U.S. arms exports from the State Department to the Commerce Department, troubling human rights activists.

“The questions, the accountability, the end-use monitoring, the oversights and the diligence to potential impact on human rights is going to be severely weakened,” said Akwei.