E pluribus unum — out of many, one — has been an official motto of the United States since June 20, 1782. Writ large, it could be the motto for climate action.

There have always been two poles representing how the world might respond to the increasingly painful reality of climate change (or indeed any global scale problem). At one pole is unity driven by our moral sensibility — a concerted national and global effort to address the gravest preventable existential threat to Americans and indeed all humanity. It is embodied in the Pope’s Encyclical from a year ago, a clarion call on the moral necessity of climate action.

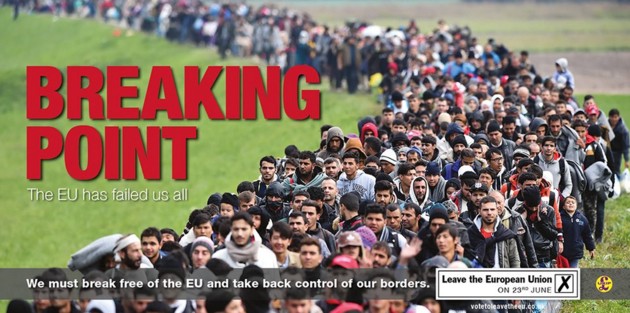

At the other pole is disunity driven by self-interest: “Après nous le déluge,” everyone for themselves, the very source of the “tragedy of the commons” that thwarts collective action. It is embodied in Trumpism and Brexit — the vote Britain just made to split from the European Union, driven in large part by scaremongering around the Syrian refugee crisis.

On this spectrum from unity to disunity, the world has, until recently, been far too close to the disunity pole for a quarter century — which is why, until recently, global emissions have been close to the worst-case trend-line. In the last two years, though, we have seen China make a game-changing deal with the United States to become the first big “developing” nation to pledge to cap its emissions. That was quickly followed by serious climate commitments from the vast majority of the world’s leading countries of the world.

And that led to nearly two hundred nations unanimously agreeing to an ongoing effort of increasingly deeper emissions reductions aimed at keeping total warming “to well below 2°C [3.6°F] above preindustrial levels.” In a reversal of the tragedy of the commons, the world united in an agreement to leave most of the world’s fossil fuels unburned — voluntarily abandoning trillions of dollars in short-term value to avoid decades and then centuries of incalculable cost from Dust-Bowlification, sea level rise, extreme weather, ocean acidification, and the like.

So humanity is now in a race to see whether the forces of unity can beat the forces of disunity. It’s now clear we have at hand the core enabling clean energy technologies to keep total planetary warming below catastrophic levels. What isn’t clear is whether we have the will and the cohesion to deploy those technologies rapidly enough to do so.

We’ve known for a while that there are scientific tipping points beyond which certain climate impacts — like the collapse of the West Antarctic ice sheet or the thawing of the carbon-rich permafrost — become unstoppable. But it appears there may also be political tipping points, where certain climate impacts cause so much widespread harm simultaneously that they simply fragment the world.

In this fatally-fractured future, countries focus almost exclusively on the ever-worsening climate devastation to their country, destroying the possibility of collective action by the world to help those worst off.

Recent events, especially Trumpism and Brexit, are omens of the disunity we face. Trump’s campaign is driven by racist statements and wildly impractical plans to wall off the country literally and figuratively from various ethnic and religious groups.

The Syrian migrant crisis “had an outsized impact on the Brexit,” as NBC News political director Chuck Todd said Friday. You can see that in the pro-Brexit poster from the U.K. Independence Party (above) — which became a major advertising campaign of the referendum — featuring thousands of male refugees streaming from Croatia into Slovenia last October.

It bears repeating that a major 2015 study confirmed: “Human-caused climate change was a major trigger of Syria’s brutal civil war.” This study found that global warming made Syria’s 2006 to 2010 drought two to three times more likely. “While we’re not saying the drought caused the war,” the lead author explained. “We are saying that it certainly contributed to other factors — agricultural collapse and mass migration among them — that caused the uprising.”

And that mass migration ultimately fueled the mass refugee crisis of the last two years, a crisis the world has utterly failed to figure out how to handle.

In a globally warmed world, we will face endless refugee crises like Syria’s

The problem from a climate perspective is that while these hundreds of thousands of refugees have led to the “world’s largest humanitarian crisis since World War II,” as the European Commission has described it, the numbers of refugees pale in comparison with what the world faces if we don’t avoid catastrophic climate change.

On the one hand, study after study are now finding that only aggressive climate action can save the world’s coastal cities from inundation by century’s end. The world should be anticipating five to six feet of sea level rise by 2100 — which by itself would generate hundreds of millions of refugees.

But at the same time, we face as many (if not more) refugees from Dust-Bowlification and the threat to our food supplies.

This map of the global drying we face uses the Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI), a standard measure of long-term drought. It is excerpted from the study, “Global warming and 21st century drying.”

We are currently on track to make drought and extreme drying the normal condition for the Southwest, Central Plains, the Amazon, southern Europe, and much of the currently inhabited and arable land around the world in the second half of the century.

Brexit and Trumpism make plainly — and painfully — visible that even rich, democratic nations deal poorly with a moderate amount of refugees, immigration, and economic dislocation. Imagine how we’ll deal with the 100-fold escalation of those problems if we fail to stop catastrophic climate change.

I’m not certain there is much middle ground in the global struggle between unity and disunity. Either the world works together to keep total warming well below 2°C — or our disunity leads to catastrophic warming and further global disunity not seen since the fall of the Tower of Babel.